State of the Homeless 2020

Governor and Mayor to Blame as New York Enters Fifth Decade of Homelessness Crisis

By Giselle Routhier, Policy Director, Coalition for the Homeless

Executive Summary

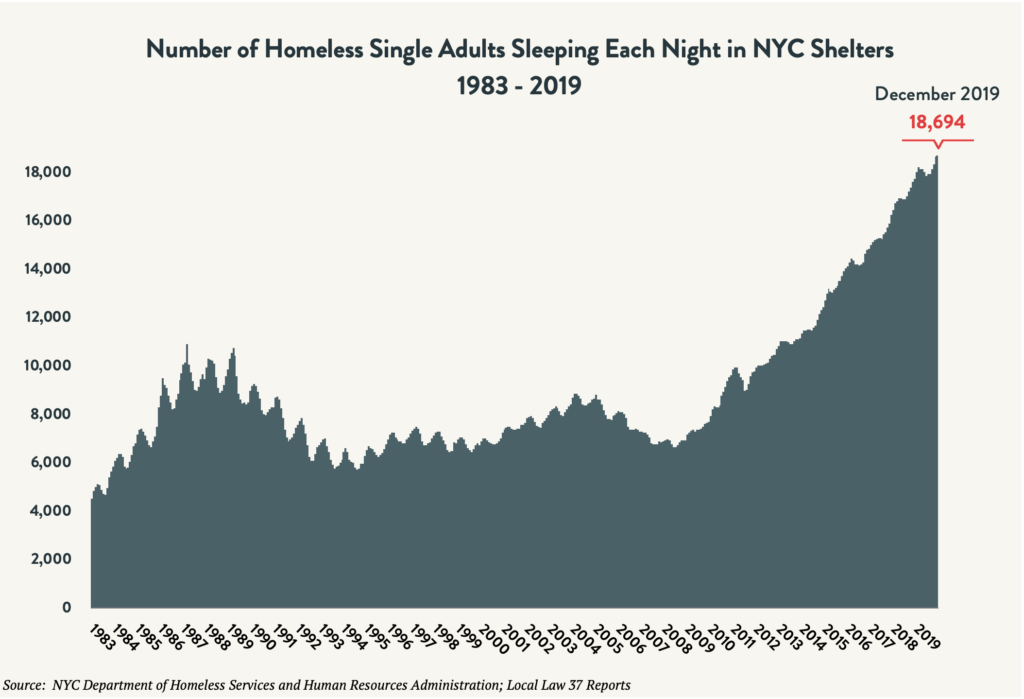

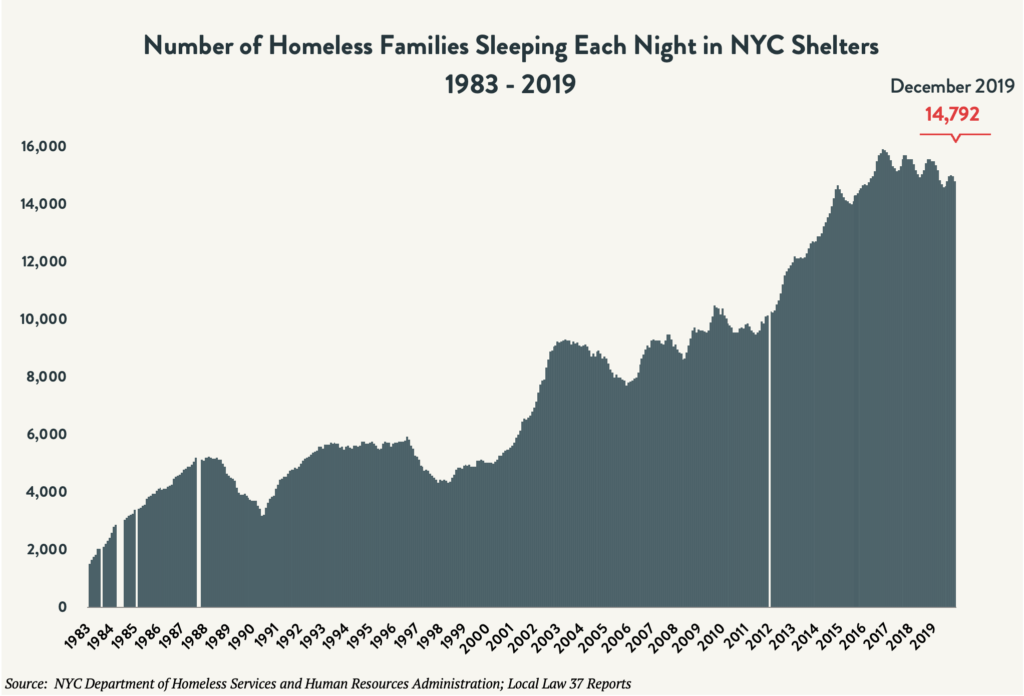

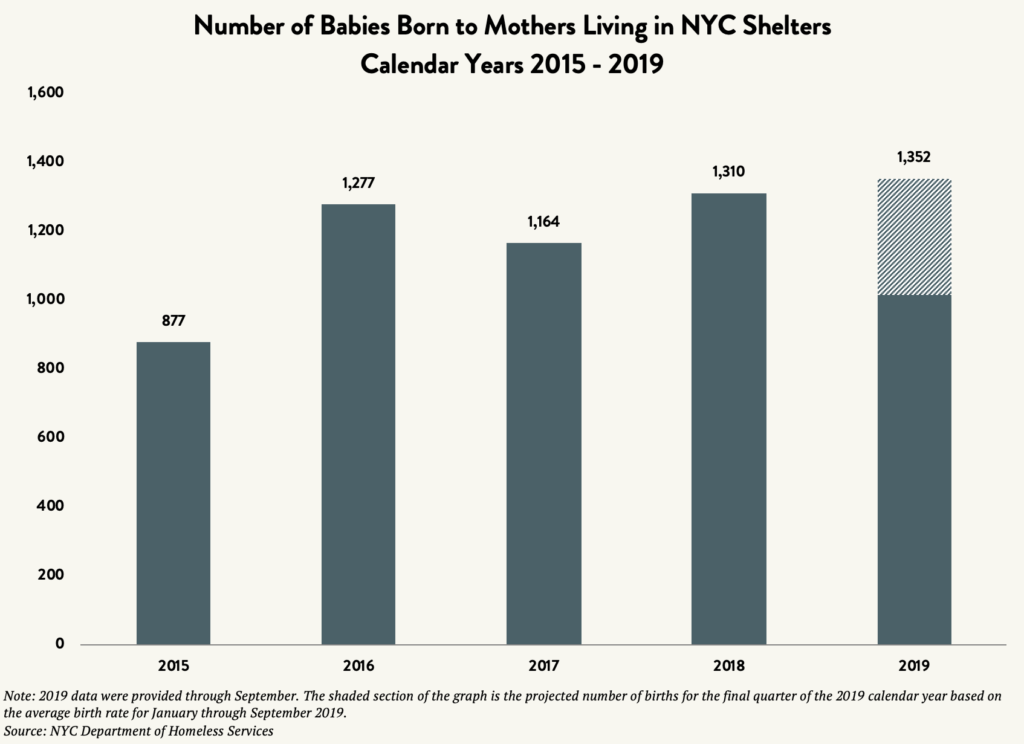

Modern mass homelessness in New York is now entering its fifth decade. New York’s catastrophic affordable housing crisis continues to fuel record homelessness throughout the city and state, devastating the lives of tens of thousands of men, women, and children. The number of single adults sleeping each night in New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters increased by a staggering 143 percent, from 7,700 in December 2009 to 18,700 in December 2019. While the number of families sleeping each night in DHS shelters has levelled off in the past three years, that figure remains stubbornly high: In December 2019, 14,792 families slept in shelters each night, a 7-percent decline from the all-time high of 15,899 in November 2016, but a 46-percent increase compared with December 2009. Shockingly, 1 in every 100 babies born in New York City last year was brought “home” from the hospital to a shelter.

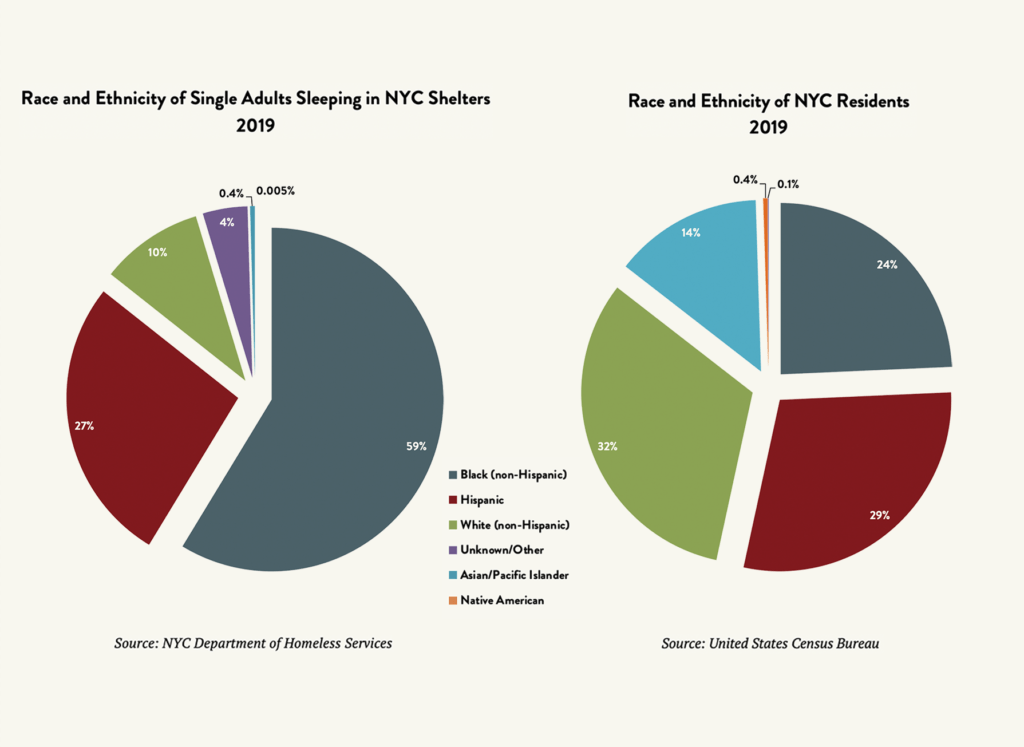

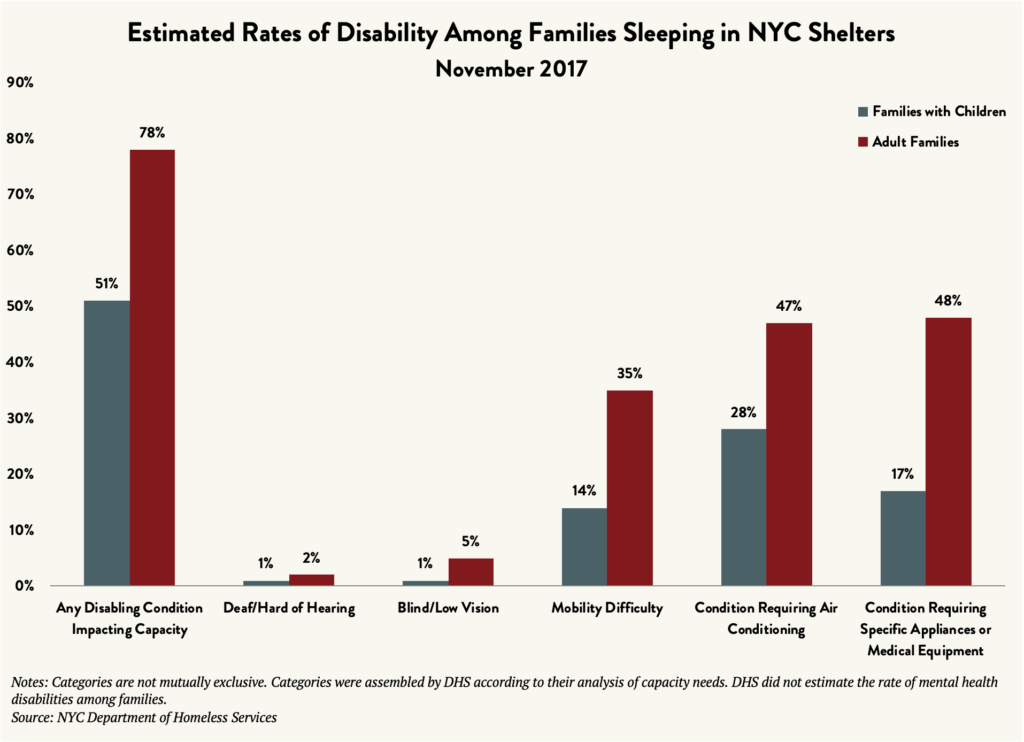

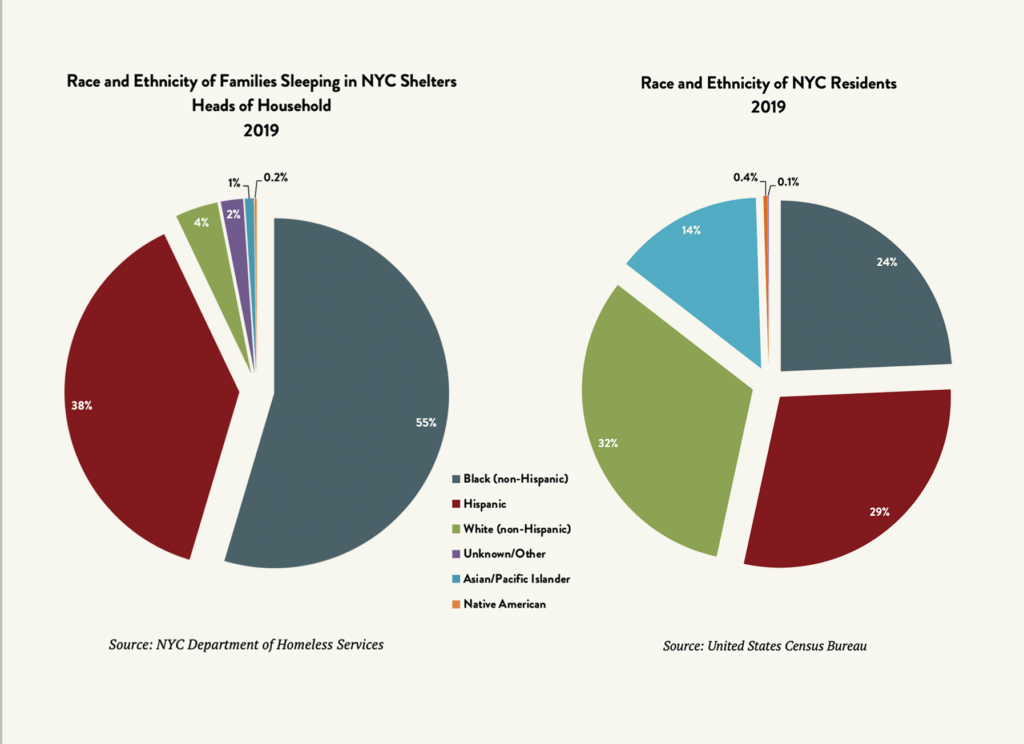

As in prior years, New Yorkers of color and people living with disabilities are disproportionately represented among those experiencing homelessness. Eighty-six percent of homeless single adults and 93 percent of heads-of-household in family shelters identify as Black or Hispanic – significantly higher than the 53 percent of New York City’s population overall who identify as Black or Hispanic. An estimated 78 percent of adult families (families without minor children), 67 percent of single adults, and 51 percent of families with children have a disability or condition that may require an accommodation to ensure they have meaningful access to shelters and services.

As disturbing as these statistics are, they constitute just the tip of the iceberg. The depth of the crisis goes far beyond what is reflected in nightly shelter census figures. State of the Homeless 2020 analyzes the institutional forces that drive record homelessness, highlights the plight of those sleeping unsheltered on the streets and in the subways, and illustrates how the City’s bureaucratic shelter application process for homeless families may actually conceal the true scope of family homelessness in New York.

Even as tens of thousands of New Yorkers struggle to avoid or overcome homelessness every day, Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo seem content with minimalist, symbolic, and too-often harmful actions made under the pretense of attempting to manage the problem, rather than taking the substantive steps needed to solve it by fully embracing proven housing solutions on a scale commensurate with the enormity of the crisis.

As noted in the Coalition’s 2019 report The Tale of Two Housing Markets: How de Blasio’s Affordable Housing Plan Fuels Record Homelessness, the Mayor’s signature housing plan exacerbates the city’s bifurcated housing market by creating a glut of high-rent units instead of investing in the production of desperately needed extremely low-rent apartments. This imbalance will finally begin to shift with the enactment of Local Law 19 of 2020, which will require the City to allocate a minimum of 15 percent of apartments to homeless New Yorkers in new City-subsidized buildings over 40 units. While the City deserves credit for increasing the legal and financial resources available to those trying to avoid eviction, Mayor de Blasio’s refusal to prioritize affordable housing for homeless families and individuals, and his recent initiatives that wrongly and disturbingly criminalize unsheltered homeless men and women, have seriously undercut efforts to reduce homelessness in our city.

Likewise, on Governor Cuomo’s watch, the number of people sleeping each night in NYC shelters has increased by 60 percent, even as he has implemented damaging cost-shifting practices each year that reduce the State’s contribution to address homelessness and squeeze the City for ever-increasing resources to pay for what once was a much more equitably shared financial responsibility. The Governor’s attempt to respond to riders’ concerns about the number of homeless people sleeping in subway cars by deploying 500 new MTA police officers evinces a profound misunderstanding of the needs of unsheltered individuals. Further criminalizing homelessness will only push people farther into the shadows, away from the help they need.

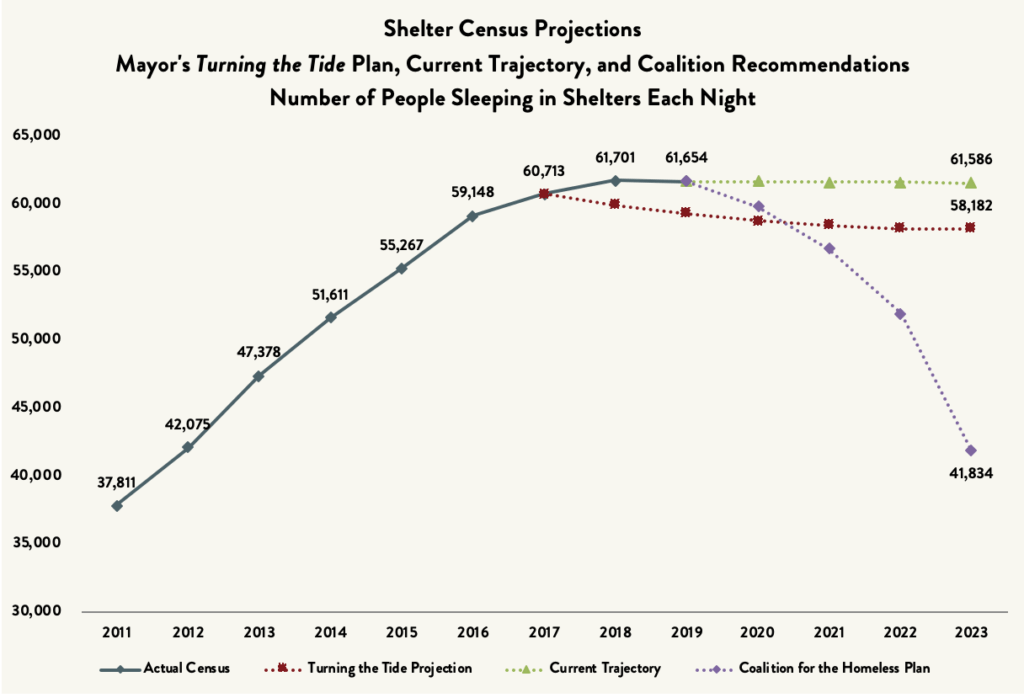

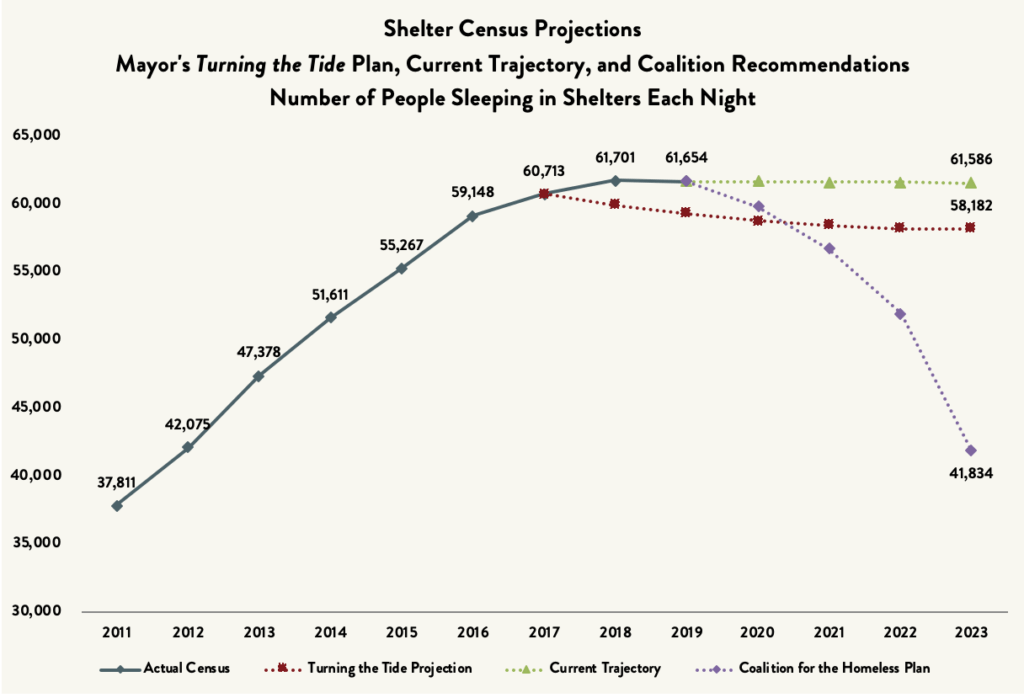

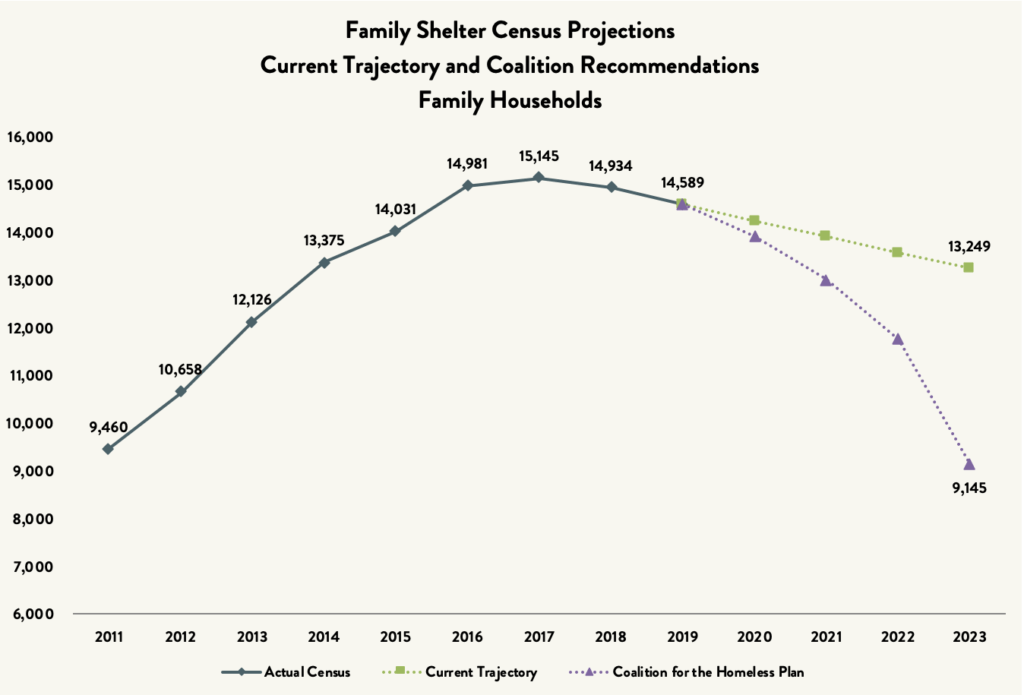

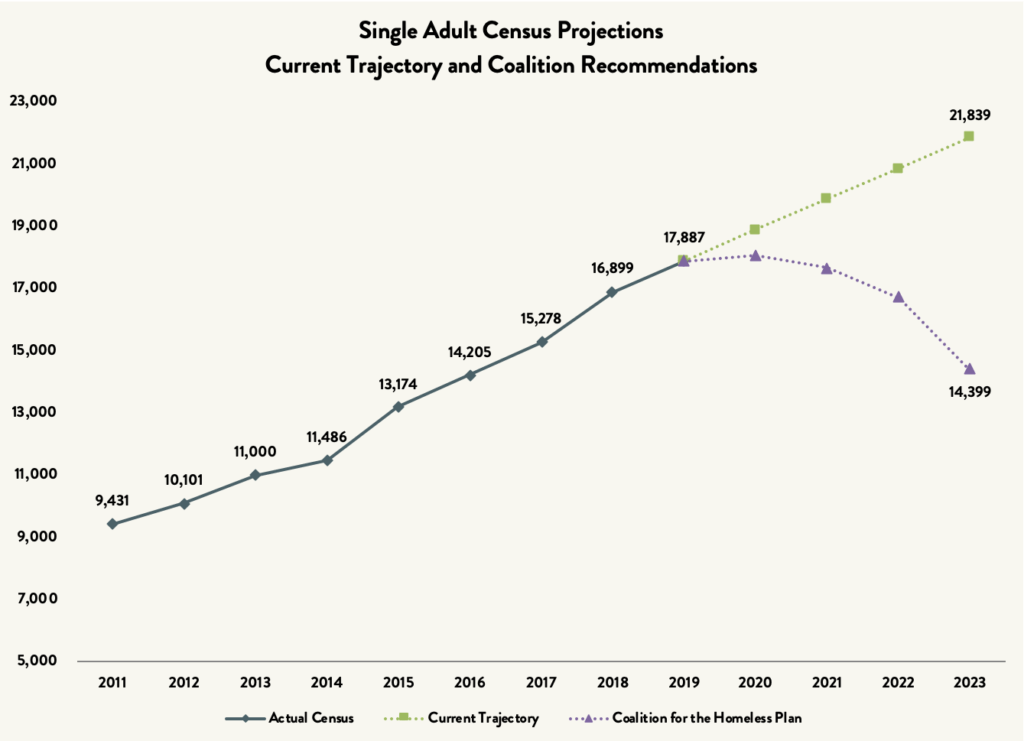

The recommendations outlined in this report are founded in proven, humane, and fiscally sound housing solutions to mass homelessness that should be top priorities for both Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio. Their implementation would reduce the New York City shelter census by 32 percent by 2023, allowing that figure to drop below 42,000 for the first time in more than a decade. The number of homeless families would decrease by more than 5,000 over the next four years, and the precipitous rise in homelessness among single adults would finally be checked. The question – asked by all New Yorkers, both homeless and housed – is whether Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio will finally muster the political courage to treat homelessness like the urgent humanitarian crisis it is.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

HOUSING

Governor Cuomo must:

- Implement the Home Stability Support (HSS) program to create a State-funded, long-term rent subsidy for households receiving public assistance who are homeless or at risk of losing their housing due to eviction, domestic violence, or hazardous housing conditions.

- Accelerate the pace of production of the 20,000 units of supportive housing pledged by the Governor in 2016 by completing them within 10 rather than 15 years, and fully fund the construction and operation of the remaining 14,000 units.

- Follow the recommendations of the Bring it Home Campaign and adequately fund existing community based housing programs for individuals with psychiatric disabilities.

- Ensure effective reentry planning for individuals being released from State prisons in order to identify viable housing options prior to each individual’s scheduled release date.

- Reform punitive parole practices that allow parole officers to exercise wide discretion and deny placement at potentially viable addresses for individuals leaving State prisons.

- Fund the creation of supportive housing specifically for individuals reentering the community from State prisons.

- Expand the Disability Rent Increase Exemption program (DRIE) to include households with a family member with a disability who is not the eligible head of household.

Mayor de Blasio must:

- Allocate at least $20 million in the fiscal year 2021 budget to help subsidize the increased production of housing mandated under Local Law 19.

- Greatly reduce reliance on SOTA and help families move out of shelters with long-term rent subsidies, including Section 8 vouchers.

- Allocate at least three-quarters of tenant-based Section 8 vouchers made available each year to homeless households so they can exit shelters.

- Accelerate the timeline for the creation of 15,000 City-funded supportive housing units by scheduling their completion by 2025 rather than 2030.

- Create an impartial appeals process through the Human Resources Administration (HRA) for individuals applying for supportive housing.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo should together:

- Fund the production of more housing specifically for single adults, separate and apart from their respective existing supportive housing commitments.

- Expand access to supportive housing for adult families – a population with disproportionately high levels of disability and complex needs.

- Implement a system of notifying supportive housing residents of their rights as tenants and clients of service providers.

- Create a standard set of practices for supportive housing providers to interview and accept residents, with an emphasis on Housing First and low-barrier entry.

SHELTERS AND SERVING UNSHELTERED INDIVIDUALS

Mayor de Blasio must:

- Apply elements of the Safe Haven shelter model to general shelters to make them more humane, respectful, and suitable for homeless individuals whose past experiences lead them to avoid shelters.

- Ensure all shelters serve individuals and families with dignity, provide a safe environment, and are adequately staffed at all times to provide meaningful social services, housing search assistance, and physical as well as mental health care and/or referrals.

- Expand the supply of Safe Havens by at least 2,000 beds to meet the needs of unsheltered individuals bedding down on the streets and other places not meant for human habitation.

- Reform the provision of food in shelters to improve quality, expand oversight, adequately accommodate the nutritional needs of shelter residents, and allow for dietary, religious, and other requirements.

- End the Subway Diversion Program and CCTV monitoring of homeless individuals, and end the practice of deploying police officers to respond to the presence of homeless people on the subways and streets.

- Administratively clear all summonses that have been issued under the Subway Diversion Program.

Governor Cuomo must:

- Reverse harmful cuts to New York City’s emergency shelter system that have resulted in the State short-changing the City by hundreds of millions of dollars over the past six years, and share equally with the City in the non-Federal cost of sheltering families and individuals.

- Conduct oversight of hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions to prevent inappropriate discharges to shelters and the streets.

- Replace the grossly inadequate $45 per month personal needs allowance for those living in shelters with the standard basic needs allowance provided to public assistance recipients.

- Permanently eliminate the statewide requirement that shelter residents pay rent for shelter or enroll in a savings program as a condition of receiving shelter.

- Immediately end the initiative to place MTA police at the end of subway lines to target homeless individuals, and halt the plan to hire 500 additional MTA police officers, which will inevitably result in the disproportionate and discriminatory persecution of homeless and low-income New Yorkers, especially people of color.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo should together:

- Implement a less onerous shelter intake process for homeless families in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining necessary documents, 2) housing history documentation is limited to the prior six months, and 3) DHS-identified housing alternatives are investigated to confirm their availability, safety, and lack of risk to the potential host household’s tenancy. For adult families, the City must accept verification of time spent on the streets from the widest possible array of sources, including outreach workers, soup kitchens, social workers, health care providers, and neighbors.

- Fund additional services for individuals living with severe and persistent mental illnesses, such as expanding access to inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, providing mental health services in more single adult shelters, and adding more Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams for homeless people.

- Establish a structure to regulate, finance, and develop a medical respite program and longer-term residential supports to address the needs of individuals with medical conditions who are released from hospitals and other institutions, including those who may not have adequate documentation of their immigration status.

THE STATE OF HOMELESSNESS

HOMELESS SINGLE ADULTS SLEEPING IN SHELTERS

Shelter Census

Over the past decade, the number of single adults sleeping in DHS shelters each night has been steadily and inexorably increasing by more than 1,000 people per year on average, due to the acute shortage of affordable and accessible housing for extremely low-income single individuals. In December 2019, their number reached an all-time high of 18,694 – a 143-percent increase from the 7,700 single adults sleeping in shelters each night in December 2009.

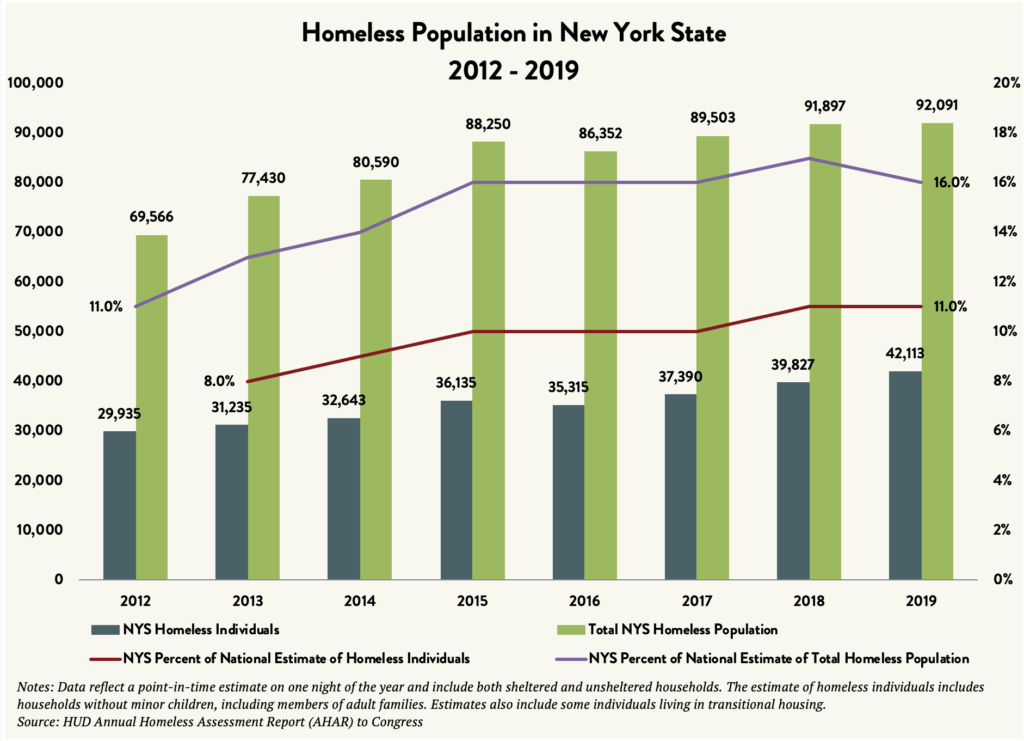

The skyrocketing number of single adults sleeping in shelters has been the primary force driving the rapid growth of homelessness in New York City as well as New York State, which in turn represents a significant proportion of the nation’s homeless population. In the past year, the number of individuals experiencing homelessness in the United States increased in 24 states and in Washington, D.C. New York saw the second-largest increase of homelessness among individuals across all states: 2,286 more individuals experienced homelessness on a single night in 2019 in New York State than on a single night the previous year. In 2019, homeless individuals in New York State represented 11 percent of all homeless individuals in the nation, up from 8 percent in 2013.

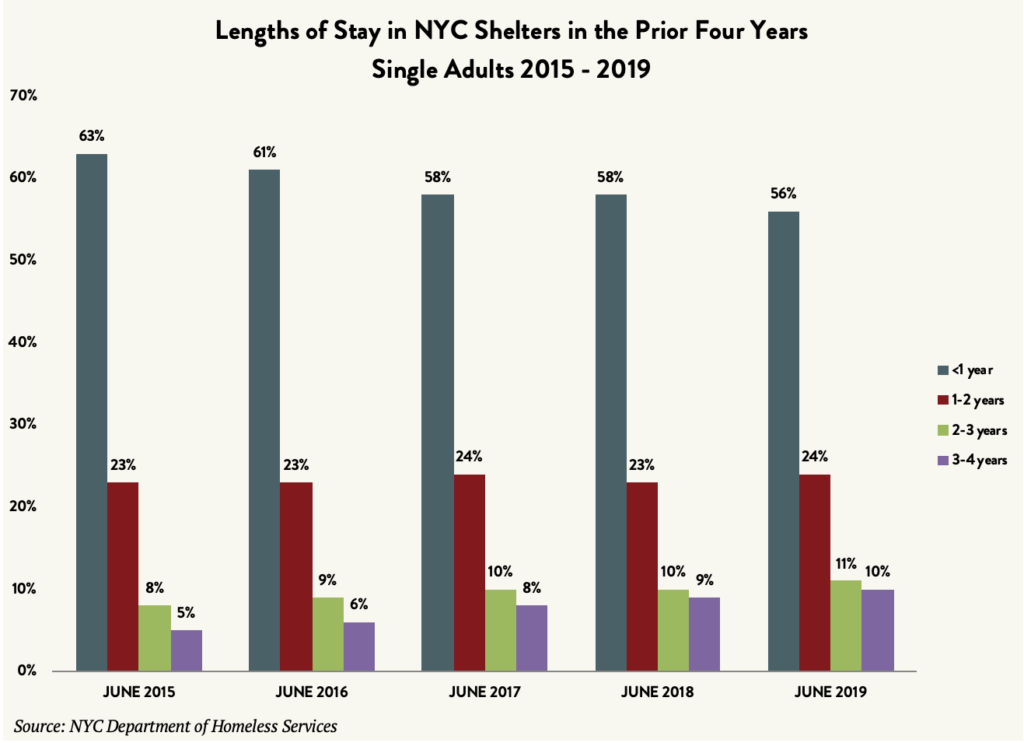

Lengths of Stay for Single Adults

Not only are more single adults entering shelters, they are remaining for longer periods of time. On average, single adults spend 429 nights in NYC shelters, up from 265 nights in 2011. One in every 10 single adults in the DHS shelter system has spent between three and four of the prior four years in shelters. Just four years ago, the rate of single adults spending this much time in shelters was half of that: only 1 in 20.

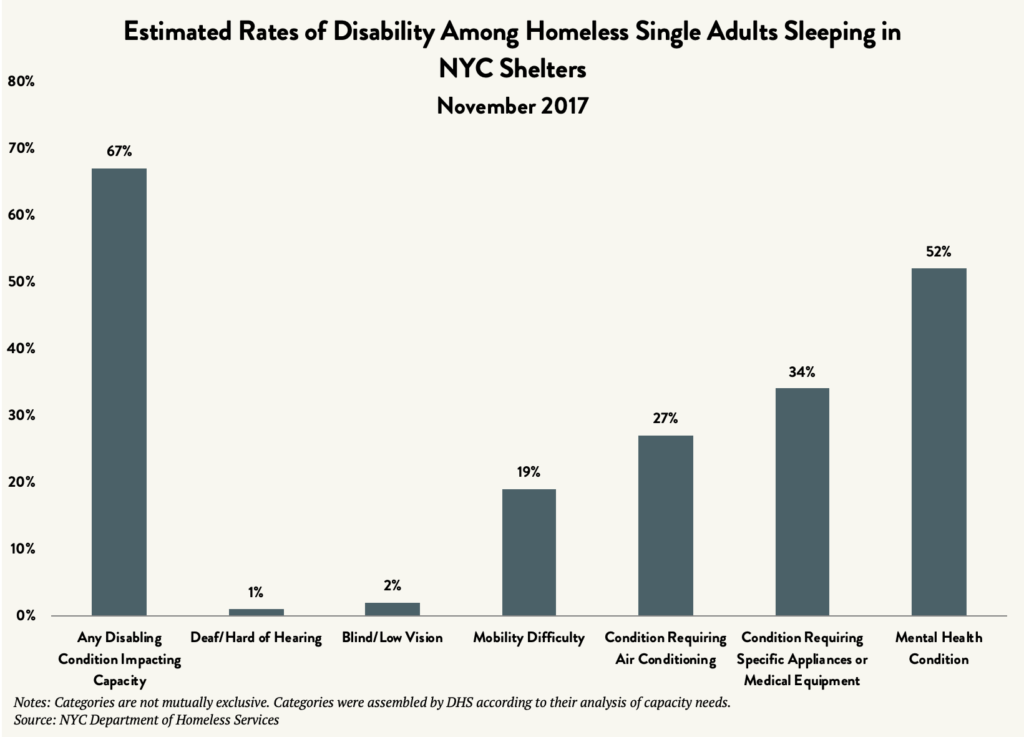

Rates of Disability for Single Adults

One of several explanations for increased lengths of stay in shelters is the significant proportion of homeless adults who have at least one disability, which often adds another layer of difficulty to the search for appropriate, stable housing. In 2017, DHS conducted a survey to determine the number of shelter residents who have a disability or condition requiring accommodation, as required by the Butler v. City of New York settlement. [1] The agency estimated that 67 percent of all single adults sleeping in the shelter system have some type of disability that requires a reasonable accommodation to ensure they have meaningful access to shelters and shelter-related services. DHS reported that the types of disabilities most likely to require a reasonable accommodation for shelter residents included those related to mobility, vision, hearing, use of medical equipment, and mental illness. DHS data also show that 16 percent of single adults receive Federal disability benefits (Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance).

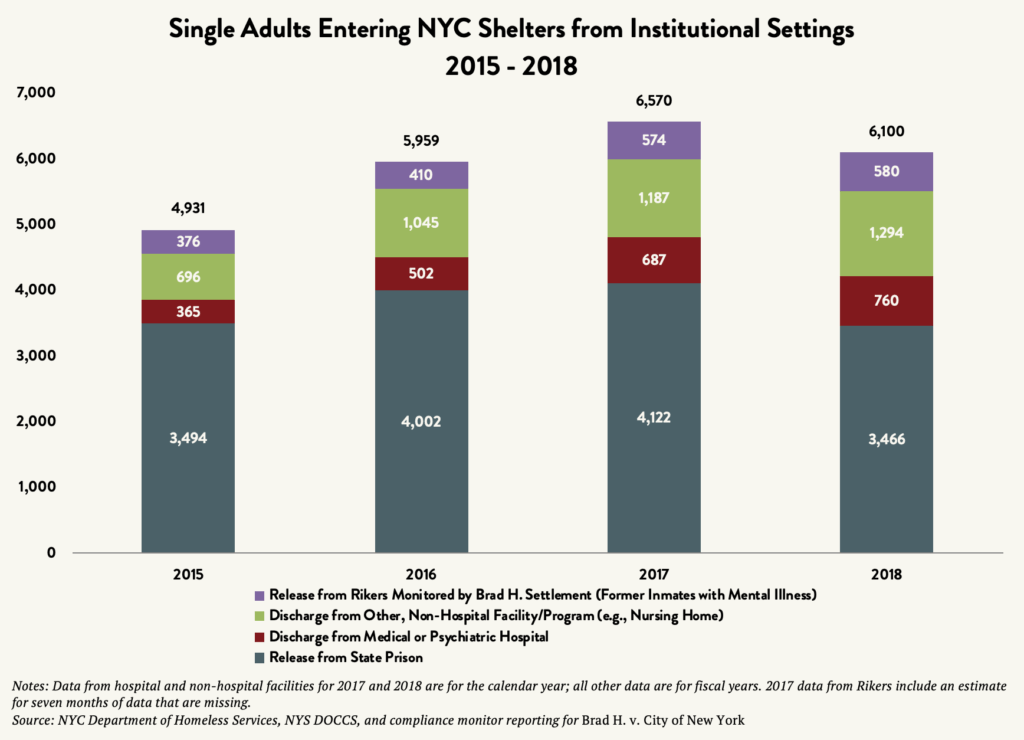

Institutional Forces that Drive Homelessness among Single Adults

Each year, around 20,000 single adults become homeless and enter the DHS shelter system. More than 6,000 of these individuals (30 percent) enter shelters directly from institutional settings. The lack of housing for individuals released from State prisons is the largest contributor to homelessness among formerly institutionalized populations. In 2018, more than 3,400 individuals were released from State prisons directly to shelters in New York City. Between 2015 and 2018 more than 15,000 such individuals were sent to City shelters by the State. At least 1,900 additional individuals who received treatment for mental illness while incarcerated entered shelters directly from City jails between 2015 and 2018, according to data tracked pursuant to the Brad H. v. City of New York settlement. [2] Moreover, an increasing number of individuals are released from hospitals and non-hospital programs, such as nursing homes. In 2018, a combined 2,054 individuals were released to City shelters from health care settings, including hospitals and nursing homes – up 94 percent from 1,061 in 2015.

Demographics of Homeless Single Adults

Homelessness disproportionately impacts New Yorkers of color: 86 percent of all homeless single adults identify as Black or Hispanic, while just 10 percent identify as White. In the overall New York City population, 53 percent of New Yorkers identify as Black or Hispanic and 32 percent identify as White. Homelessness is unequivocally a racial justice issue, and is one manifestation of historic and persistent housing discrimination, biased economic and housing policies, extreme income inequality, and disproportionately high levels of poverty among people of color, as well as biased policing and incarceration in communities of color.

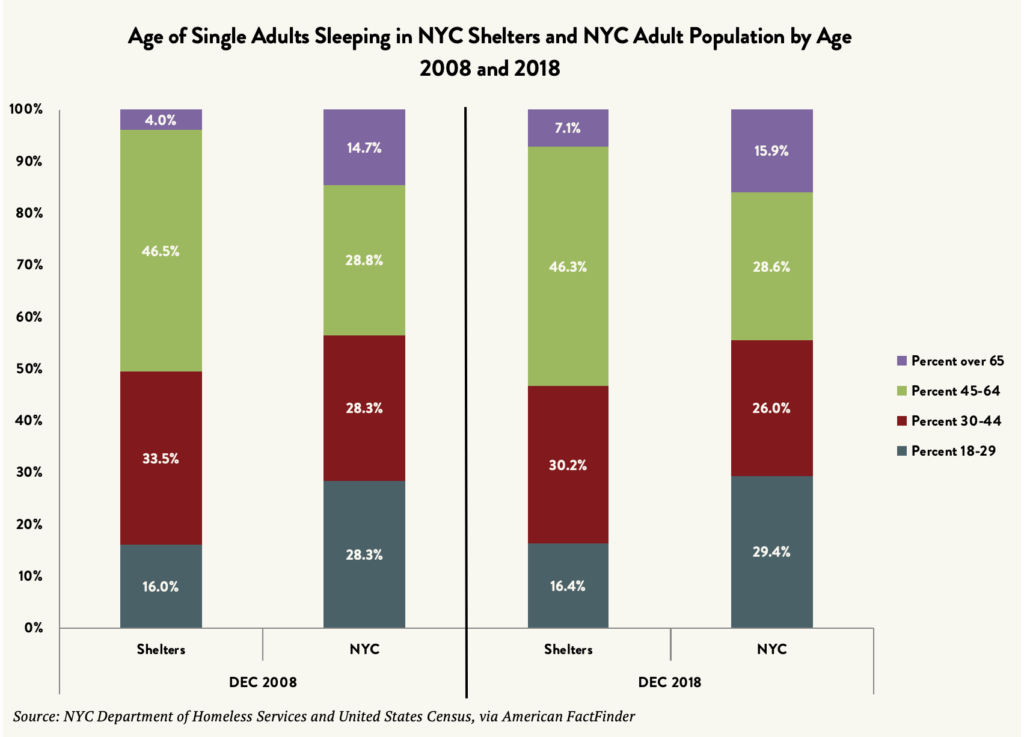

Furthermore, the number of seniors sleeping in shelters is increasing as a percentage of the overall single adult shelter population. At the end of 2018, 7 percent of homeless single adults were older than 65, up from 4 percent in 2008. Individuals sleeping in DHS shelters for adults are more likely to be older than 45 than the general NYC population, and less likely to be younger than 30. [3]

UNSHELTERED HOMELESS ADULTS

Experiences on the Streets

Contrary to the common narrative that people sleeping on the streets are “service resistant,” most unsheltered homeless New Yorkers have previously slept in the shelter system and have determined that it does not meet their needs. Outreach workers have little to offer other than a trip back to the shelter system, when what those on the streets truly need is permanent housing and low-threshold Safe Haven shelters. In 2017 and 2018, the Coalition for the Homeless conducted an extensive survey of individuals sleeping on the streets and in the transit system; the Coalition’s findings and report are forthcoming. Some of the main takeaways from these interviews are:

- More than three-quarters of those interviewed on the streets reported that they had stayed in the DHS shelter system at some point.

- The majority of respondents were unwilling to return to the shelter system because they feared for their safety and/or previously experienced difficulty following the rules and procedures.

- Two-thirds of those interviewed were assessed to have mental health needs; nearly one-third were assessed to have multiple disabling conditions, doubtless exacerbated by sleeping rough.

- The vast majority of respondents had been approached by City outreach teams, but they were not offered what they desire and need most: housing.

Safe Havens

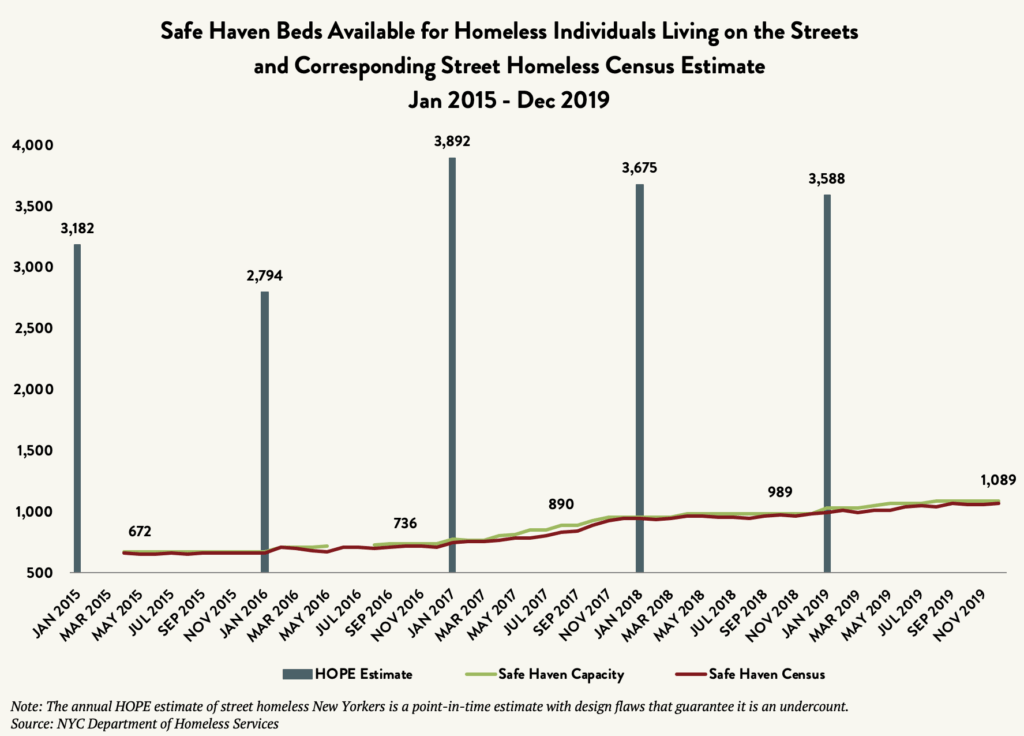

The survey responses above are supported by data provided by the City. Between 2015 and 2019, the City increased the number of beds in low-threshold Safe Haven shelters by 417. As soon as the new beds were brought online, they were immediately filled, indicating that people sleeping on the streets are willing to come inside if they are able to avoid the general shelter system and have access to a shelter option that appropriately meets their needs. Safe Havens have many features that differ from the traditional shelter system: They are often smaller, employ a higher ratio of social services staff and fewer law enforcement staff, exercise flexibility in their rules, and better tailor service plans to meet individual needs.

The number of Safe Haven beds is paltry in comparison to the number of homeless New Yorkers sleeping on the streets and in transit facilities, which the City last estimated at nearly 3,600 individuals. This figure is undeniably a significant undercount of unsheltered New Yorkers because 1) it fails to include anyone sleeping in non-visible or privately owned spaces, such as bank vestibules, 2) the annual estimate is made on a single night during the coldest month of the year, when many people move to locations offering greater protection and less visibility, and 3) the City makes concerted efforts to bring people into shelters in advance of the annual “count.”

FAMILY HOMELESSNESS

Shelter Census and Eligibility

While homelessness among families has declined slightly since the all-time high set in 2016, nearly 15,000 families currently sleep in NYC shelters each night, up 46 percent since 2009.

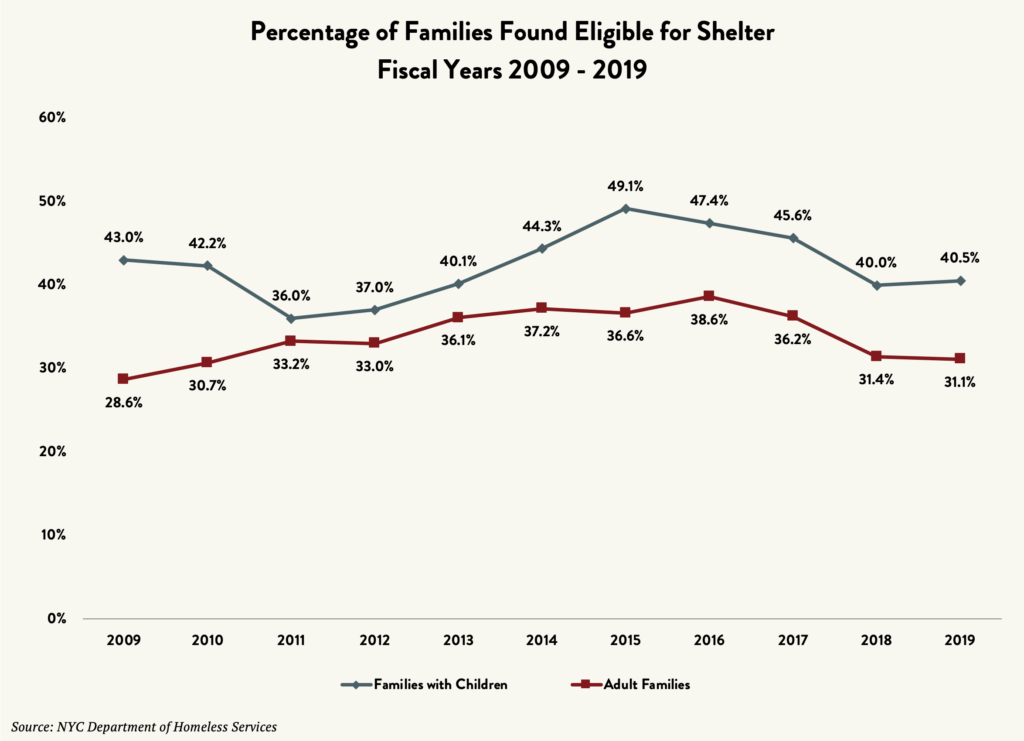

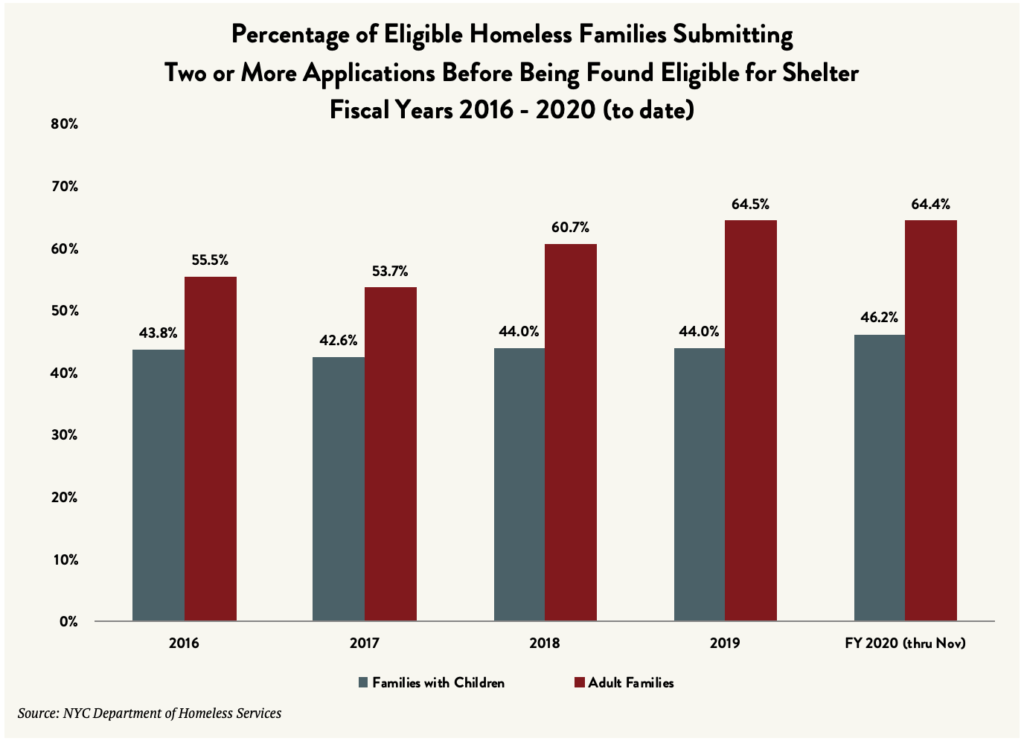

The recent slight decrease in the family shelter census must, however, be considered in the context of the majority of family applicants that are turned away at the front door of the system.[4] The percentage of families with children who were found eligible for shelter upon application decreased to only 41 percent in 2019, down from 49 percent in 2015. This drop in shelter eligibility approvals indicates that the onerous bureaucratic processes and gatekeeping at the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) intake center for homeless families are artificially suppressing the family shelter census. The impact of these bureaucratic obstacles is underscored by the fact that in fiscal year 2020 to-date, 46 percent of families with children have had to submit more than one application before ultimately being found eligible – the highest rate of reapplication in the past five years.

Adult families applying for shelter have an even lower eligibility rate: In 2019, just 31 percent of adult family applicants were found eligible for shelter, down from 39 percent in 2016. These statistics reflect average eligibility rates across the year, but the rate in any given month may in fact be much lower. As recently as November 2019, the eligibility rate for adult families reached an all-time low of just 26 percent. The difficulty adult families face when applying for shelter is manifest in this damning statistic: 65 percent of all applicants had to submit two or more applications before officially being deemed “homeless” by the City and granted a shelter placement in fiscal year 2019.

The marginal decrease in the family shelter census after 2016 may thus simply reflect a decline in the eligibility rates for both families with children and adult families without minor children, together raising serious questions about an eligibility process that far too often denies shelter placements for eligible homeless families.

Rates of Disability for Families

In 2017, DHS conducted an analysis of rates of disability among people living in shelters, as required by the Butler v. City of New York settlement. [5] The results show extremely high rates of disability among adult families, including physical disabilities and mobility impairments. An estimated 78 percent of adult families include a member with a disability according to the population analysis. Notably, the City did not seek data on mental health issues or developmental or intellectual disabilities for people in families, and therefore the actual rates of disability are likely much higher than reported. Likewise, more than half of families with children were estimated to include a member with a disability that may require an accessible shelter placement. DHS data also show that 14 percent of families with children and 30 percent of adult families include at least one family member who receives Federal disability benefits (Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance). In fiscal year 2019, 4,820 unique adult families and 25,209 unique families with children (including 44,370 unique children) spent at least one night in the shelter system.

Race and Ethnicity of Homeless Families

Family homelessness, like homelessness among single adults, disproportionately impacts people of color. Among family heads-of-household, 55 percent identify as Black (non-Hispanic) and 38 percent identify as Hispanic. Just 4 percent of family heads-of-household identify as White, compared with 32 percent of the New York City population. Altogether, at least 94 percent of families in NYC shelters are headed by people of color.

Homeless Children and Students

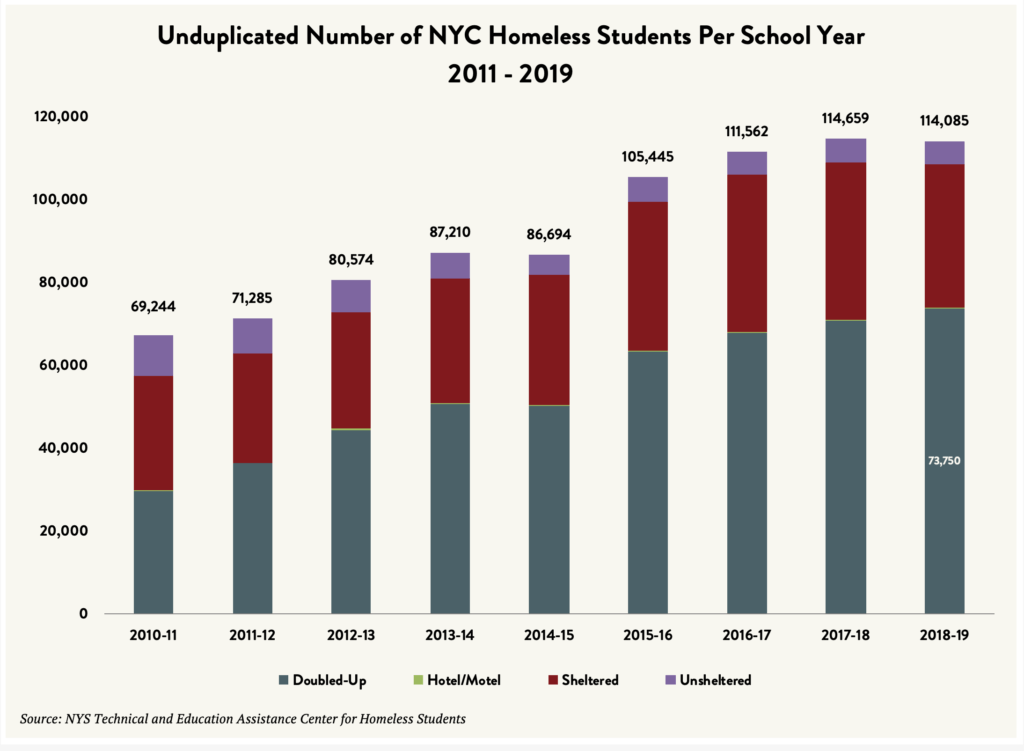

In 2018, more than 1,300 babies were born to parents living in DHS shelters. In 2019, the number of babies going “home” from the hospital to a shelter is expected to surpass 1,350, a five-year high. Based on estimates of the total birth rate, 1 in every 100 babies born in New York City is born homeless.

While the number of babies born to mothers living in shelters is on the rise, the number of homeless students sleeping in shelters decreased in the 2018-19 school year. However, the overall number of students experiencing homelessness remained near the all-time high of 114,000 due to an increase in the number of schoolkids living doubled-up with family or friends. There can be no doubt that the suppression of the family shelter census contributes to the unprecedented number of homeless students who are living doubled-up with family or friends in New York City. Nationally, the number of homeless students hit an all-time high in the 2017-18 school year: During this period, 1.5 million students experienced homelessness. [6] The same report found that only California and Texas had more homeless students than New York State.

CONCLUSION

Homelessness remains at historically high levels, with certain subpopulations of New Yorkers disproportionately affected by the shortage of affordable housing at the root of this ongoing crisis. A staggering number of homeless single adults are sleeping in New York City shelters – the highest level since the advent of modern mass homelessness in the late 1970s. Many homeless single adults have complex needs related to their disabilities or histories of institutionalization that contribute to longer lengths of stay in shelters and make it more difficult for them to navigate the shelter system and compete for scarce affordable apartments. Due to grossly inadequate discharge planning, the State has contributed substantially to the unchecked growth in single adult homelessness in New York City by releasing prisoners directly to the City’s shelter system.

The presence of homeless people on the streets remains a hard-to-measure phenomenon, but one with very real consequences. The challenges homeless New Yorkers sleeping on the streets face are numerous and exacerbated by the lack of ready access to housing and Safe Haven shelters. The chaotic, unsafe, and bureaucratic DHS shelter system does not adequately meet the needs of homeless New Yorkers staying outside. Instead of solving the real problems at hand, both Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo have turned to increased policing, harassment, and persecution of vulnerable individuals struggling to survive in public.

Homelessness among families in New York City has declined slightly in recent years, but the low eligibility rates for shelter applicants are masking the larger problem. The gatekeeping at the family intake centers is artificially suppressing the family shelter census. This results not only in an unwarranted delay in or denial of access to safe shelter for eligible families, but also in an underestimate of the number of families without safe, appropriate, and affordable housing of their own. This is especially disturbing considering the tragically large proportion of infants spending their early formative months and years without the stability of a home. Likewise, adult families have particularly high levels of need, and yet they experience the most daunting challenges of all in navigating the inscrutable shelter application process.

Homelessness is unequivocally an issue of racial justice. The disparity between the rates of homelessness among people of color and White New Yorkers is enormous. In reality, homelessness is rare among White New Yorkers. The continued lack of urgency from Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio to end homelessness can only lead to even wider disparities and, unless each of them changes course, they will fail to achieve true justice and equity for New Yorkers of color. Every New Yorker deserves a home.

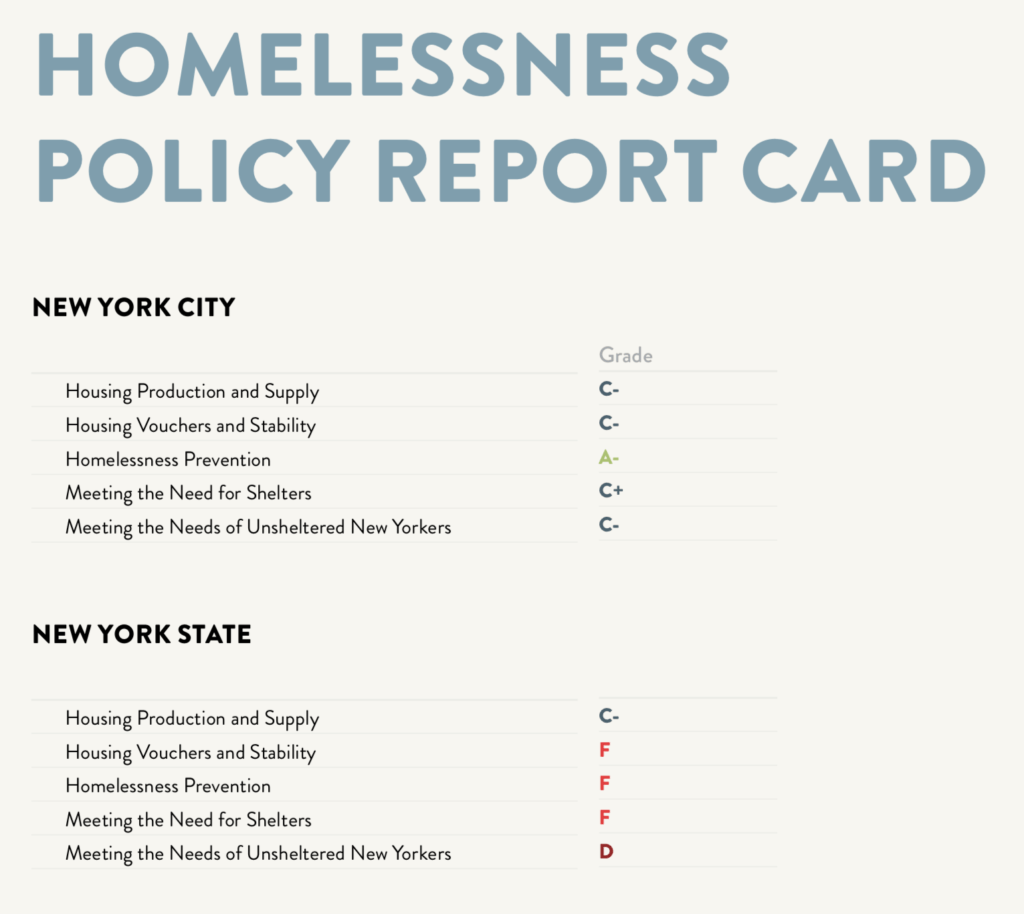

HOMELESSNESS POLICY REPORT CARD 2020

HOUSING PRODUCTION AND SUPPLY

City: C- State: F

Affordable Housing

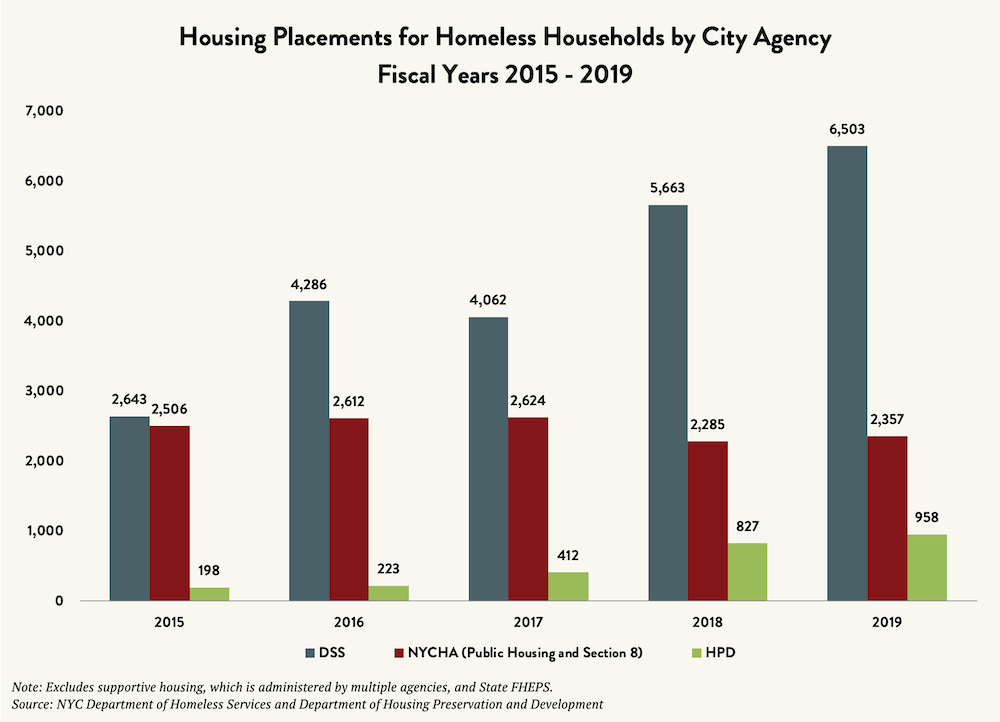

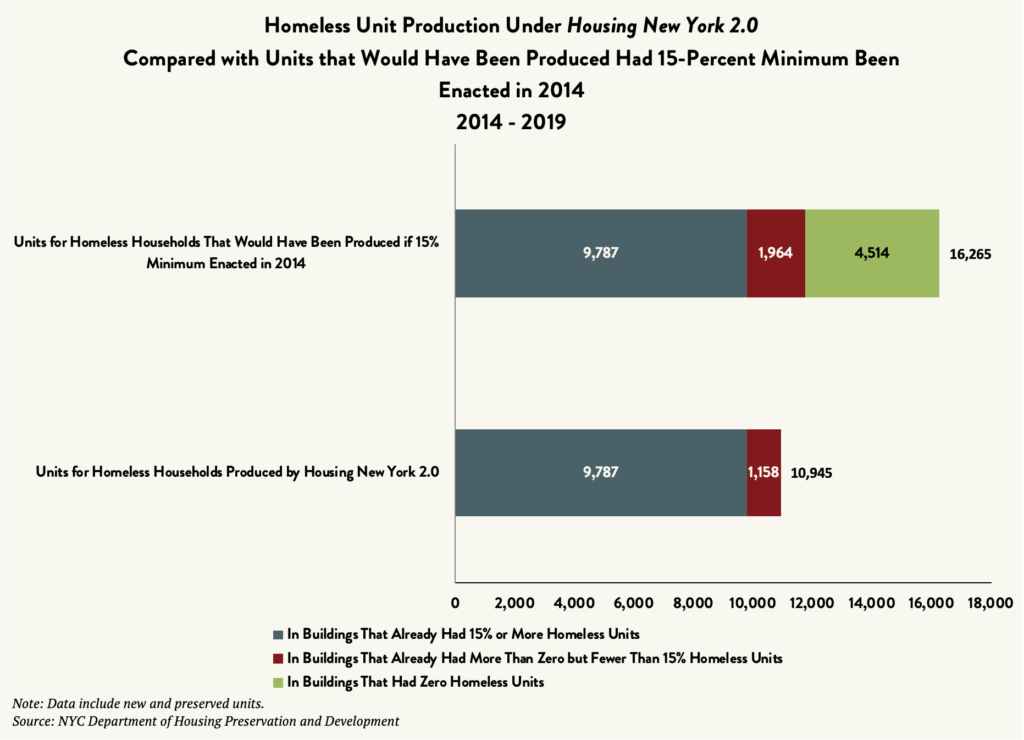

Mayor de Blasio’s affordable housing plan, Housing New York 2.0 (“HNY”), continues to fail to adequately address the city’s homelessness crisis. Because of the low rate of production of housing for homeless New Yorkers through HNY, fewer than 1,000 homeless households moved from shelters into apartments through the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) in 2019 – the lowest of any agency that administers housing assistance for homeless New Yorkers. [7] Regrettably, with the shelter census at near-record levels, the number of apartments made available to homeless New Yorkers from HPD and the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) grew by merely 203 in 2019. Creating new apartments for homeless people has clearly not been a top priority of Mayor de Blasio’s housing agencies: Between 2014 and 2019, 31,000 newly constructed apartments – 41 percent of all new apartments produced under the plan during that period – were in buildings that provided absolutely no housing for homeless New Yorkers. While some buildings did set aside more than 15 percent of their apartments for homeless households, a large portion of these units were part of the Mayor’s separate supportive housing commitment.

Meanwhile, in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, almost 700 apartments created under Mayor de Blasio’s affordable housing plan have “gone to market” since the plan’s inception, which means the apartments were advertised through third-party sites such as StreetEasy after the City was unable to find eligible, interested renters through the Housing Connect lottery. [8] All of these apartments were built for households earning above 100 percent of the area median income (AMI), with most of the apartments reserved for households at 120 percent of AMI. A family of three with an income at 120 percent of AMI earns about $115,000 a year. Apartments created for these households are still counted toward the City’s “affordable” housing targets, even if they are unable to find any interested tenants who earn the requisite six-figure salaries. By contrast, it is not uncommon for HPD to receive 300 to 500 applications for each apartment created for lower-income New Yorkers at or below 30 to 50 percent of AMI. [9] This stark contrast in demand for new apartments illuminates the mismatch between the Mayor’s housing plan and the dire need for housing for homeless and extremely low-income New Yorkers, who clearly have the most pressing need for truly affordable housing.

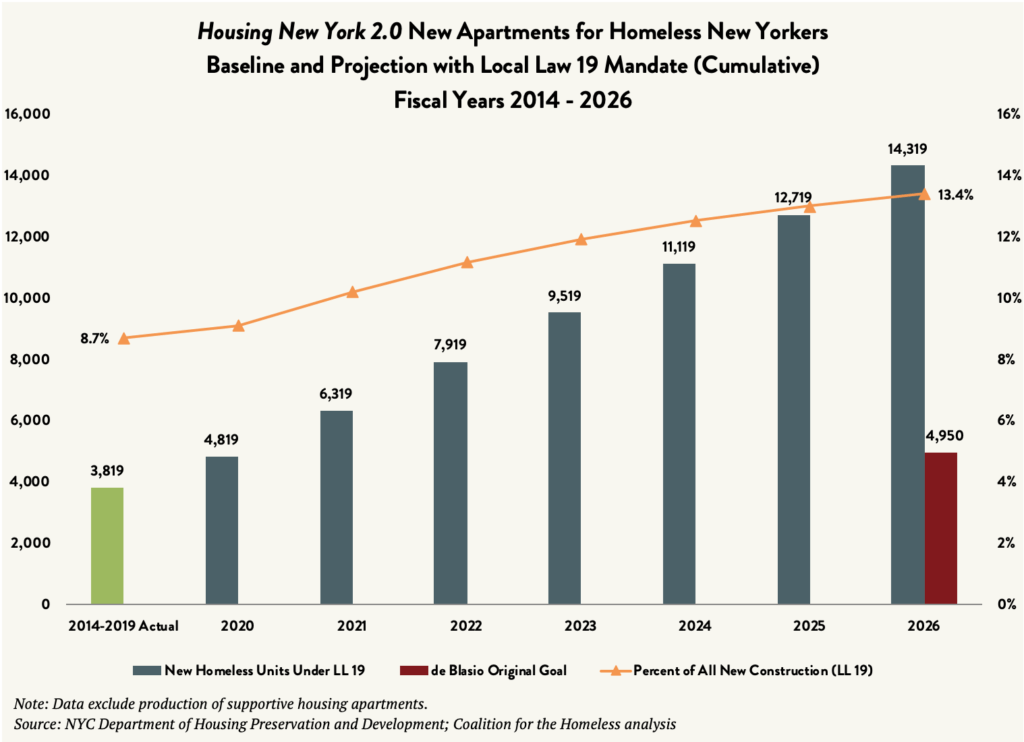

In December 2019, the New York City Council passed legislation that became Local Law 19 of 2020. Beginning on July 1, 2020, this historic legislation will require all new rental developments with more than 40 apartments that receive City financing to set aside a minimum of 15 percent of apartments for homeless individuals and families. If this 15-percent set-aside had been required in every rental project with more than 40 apartments from the beginning of the Mayor’s housing plan in 2014, the City would have created 5,320 additional apartments (about 900 per year) for homeless New Yorkers, in addition to the 3,819 new apartments the City actually financed for homeless households during this time. [10] With this level of production in place prospectively, the City can expect to have built more than 14,000 new apartments for homeless households by 2026 (separate and apart from the Mayor’s commitment to create supportive housing), nearly three times the Mayor’s original Housing New York 2.0 goal.

At the same time, the Governor often touts his $20 billion housing plan, but the truth is that only a small portion of that plan represents increased State investment in producing more affordable housing. Most of the $20 billion consists of the ongoing costs of sheltering homeless New Yorkers, the baseline annual funds for various housing programs, and a large aggregate amount from Federal tax credit investments used to help finance housing development over time.

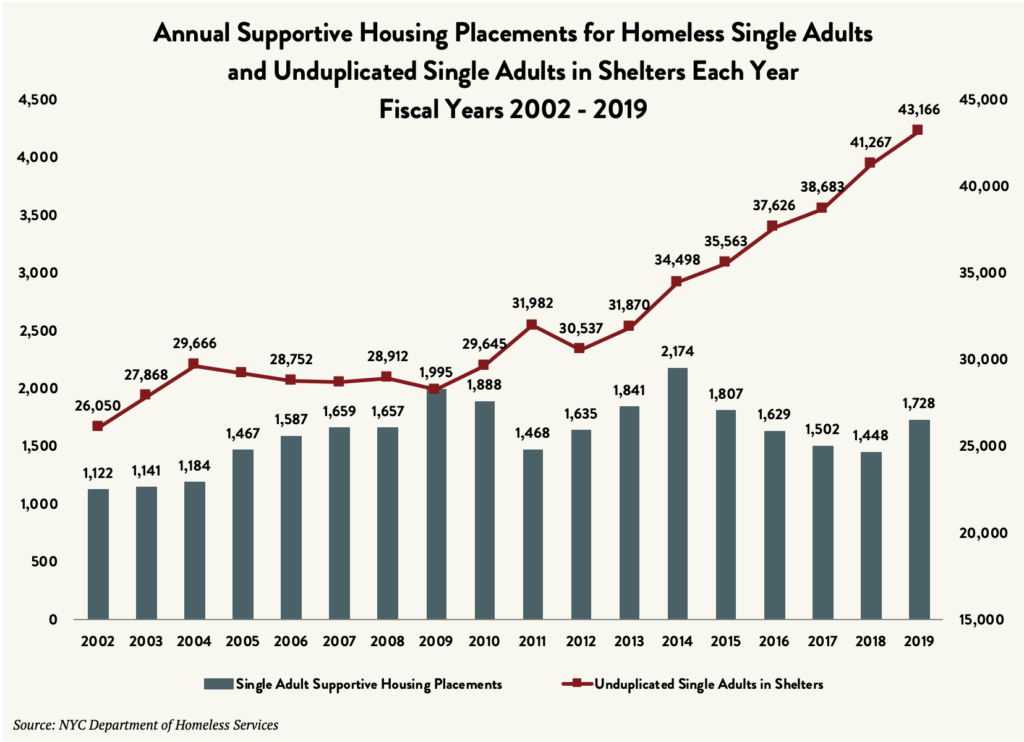

Supportive Housing

More than 1,700 homeless adults moved into supportive housing in fiscal year 2019, a 19-percent increase from the 14-year low in 2018. However, more than 43,000 homeless single adults spent at least one night in the DHS shelter system in 2019. With more than half of single adults in shelters estimated to have a mental illness, and many of them likely eligible for supportive housing, the rate of placement into supportive housing is still far too low to meet the need. The demand for supportive housing remains extremely high, with five approved supportive housing applications for each vacancy.

The process of applying for and obtaining supportive housing is needlessly complex, bureaucratic, and rife with problems for the vulnerable individuals meant to benefit from this critical resource. To access supportive housing, a prospective tenant must complete an HRA 2010e application, which requires a psychosocial assessment, a separate psychiatric evaluation, and the assistance of professional staff who must submit the application. In recent years, the Department of Social Services (DSS) has implemented new policies in response to the Federal “coordinated entry” mandate, and applicants are assigned a vulnerability score based in part on the number of “systems contacts” they have had with various City agencies. This scoring system poses accuracy problems and can misrepresent the needs of people who are disengaged – sometimes intentionally – from government agencies. Notably, there is no official, impartial appeals process for an applicant wishing to challenge an eligibility determination or vulnerability score. The supportive housing application process is unnecessarily complex and onerous for homeless applicants, who must rely on caseworkers to advocate for them with application reviewers and communicate application status updates to them.

Once an application is approved, a prospective tenant faces a new set of hurdles before receiving keys to an apartment. Applicants’ experiences vary widely during the interview stage as there is no central oversight to ensure consistent best practices among housing providers – a negative byproduct of having multiple sources of government funding and regulations for supportive housing. This inconsistency is extremely challenging for many applicants.

For example, although homeless applicants have already submitted extensive documentation with their 2010e applications, some supportive housing providers ask them to submit additional materials. Some applicants report having to complete complex forms during the interview, including paperwork that waives their right to manage their own money and benefits. On occasion, and without advance notice, applicants are required to undergo an additional mental health evaluation, or to demonstrate their ability to evacuate a building in a very short amount of time. Because of inconsistencies among providers, applicants are often left confused, overwhelmed, and unprepared for the interview process. All of these barriers illustrate how far supportive housing has moved away from a true Housing First model. [11]

Many people living in supportive housing apartments are not aware of their tenancy rights or the rules particular to their program. It can be difficult to ascertain which regulatory schemes in the patchwork of supportive housing programs govern a particular building. Supportive housing residents often do not know where to turn when their tenancies are threatened or they need help with money management. As the City and the State work to increase the supply of supportive housing, it will become even more important to ensure that residents are fully informed of their rights and know where to obtain assistance when they need it.

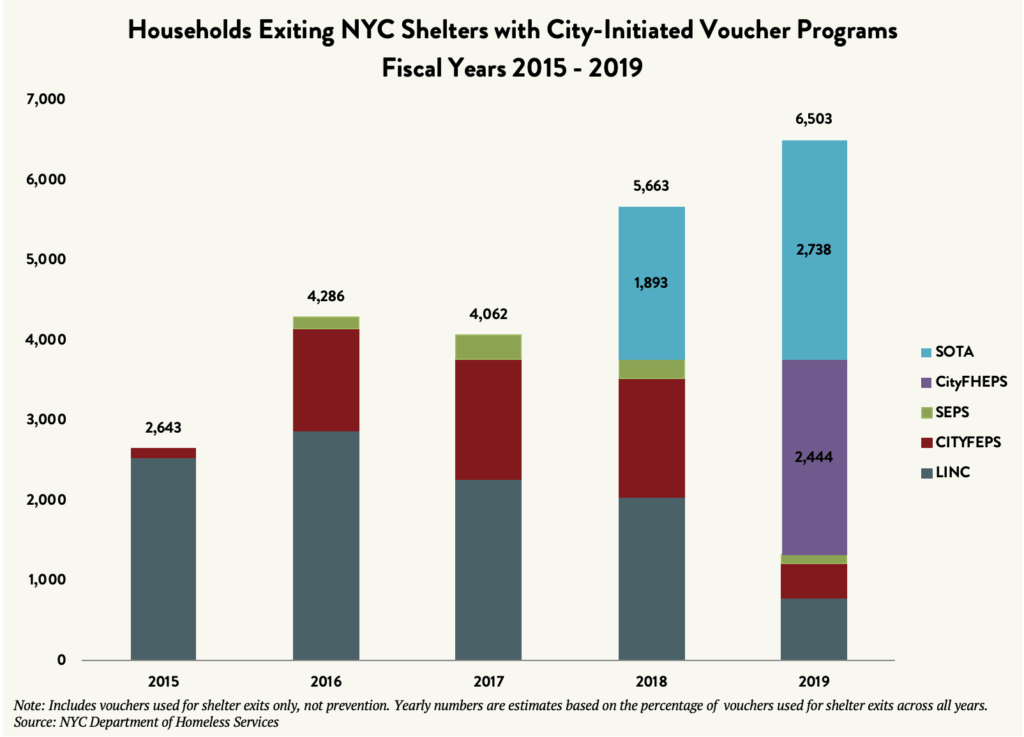

HOUSING VOUCHERS AND STABILITY

City: C- State: F

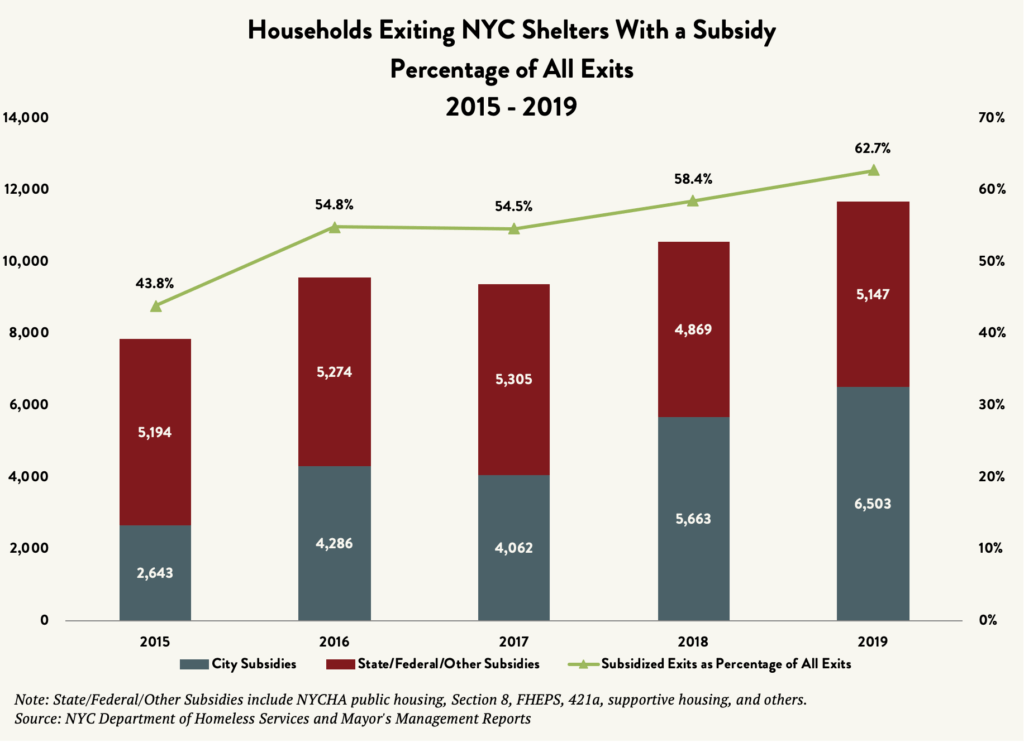

The City is increasingly relying on the Special One-Time Assistance (SOTA) program to help families and individuals move out of shelters. SOTA provides one year of rent assistance to help shelter residents move within the five boroughs, beyond New York City, or outside of New York State. In 2019, more homeless families secured housing using SOTA than any other City program: 42 percent of all households leaving shelters with a City subsidy in 2019 did so through SOTA. The use of all other long-term City voucher programs combined has been steadily declining since 2016. According to the most recent data, including the first quarter of fiscal year 2020, 5,356 households have moved out of shelters with SOTA, comprising 21 percent of all households that have moved out of shelters with City-funded rent subsidies since Mayor de Blasio took office in 2014.

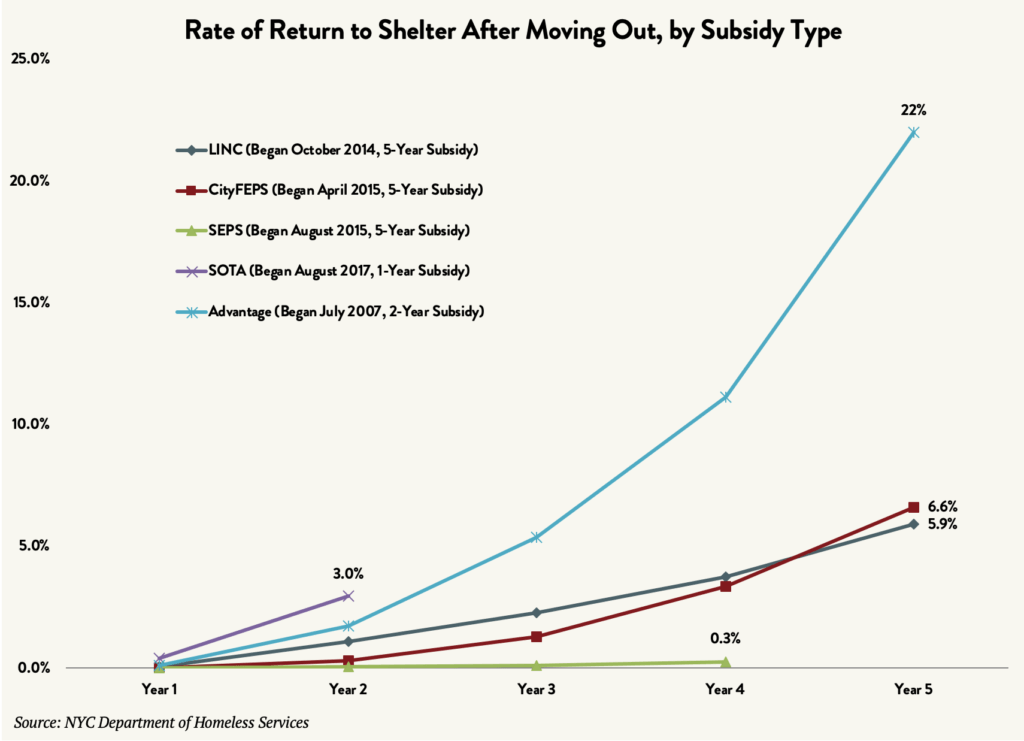

The City’s reliance on SOTA is problematic in part because of its short-term nature, [12] as rent assistance is limited to one year. Between 2006 and 2011, Mayor Bloomberg experimented with a series of short-term rent vouchers for homeless households, with the last iteration being the Advantage program, which offered assistance for up to two years. Even before the Advantage program was abruptly ended in its fourth year after the State pulled its funding share and the City followed suit, more than 10 percent of families that had moved out with the program were already back in the shelter system.

It is still too early to tell how many SOTA recipients will ultimately end up back in the NYC shelter system, but it is worth noting that at the two-year mark, we are already seeing a 3-percent return rate – one percentage point higher than the return rate from Advantage in its second year. The return rate for SOTA would also fail to capture households who used SOTA to move to a different city and who, upon losing their housing, may not be able or willing to return to the NYC shelter system.

All other City-funded long-term subsidies have low return rates: LINC, CityFEPS, and SEPS have all had return rates of less than 5 percent four years after first being implemented. The City consolidated LINC, SEPS, and CityFEPS into the CityFHEPS program in late 2018. It is too early to analyze return data from this consolidated program, but it is reasonable to assume it will remain similar to the programs it subsumed.

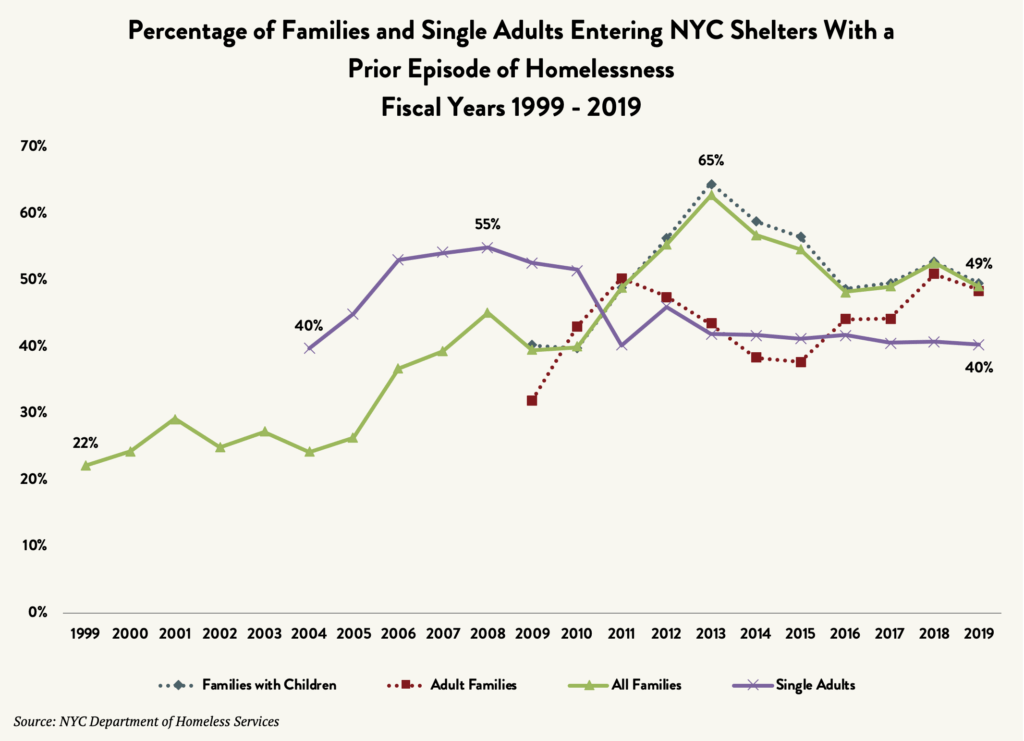

Alarmingly, homelessness is all too often a repeat occurrence among families and individuals sleeping in shelters. In fiscal year 2019, half of all families and 40 percent of all single adults entering the shelter system had stayed in a shelter at some point earlier in their adult lives. The rate of shelter return for families with children is down from the all-time high of 65 percent in 2013 (following the end of the Advantage program), but it is still extraordinarily high and reflects a lack of housing stability for many families exiting homelessness. Repeat episodes of homelessness among adult families have increased since 2015, while the rate of return among single adults has remained consistent for the past seven years.

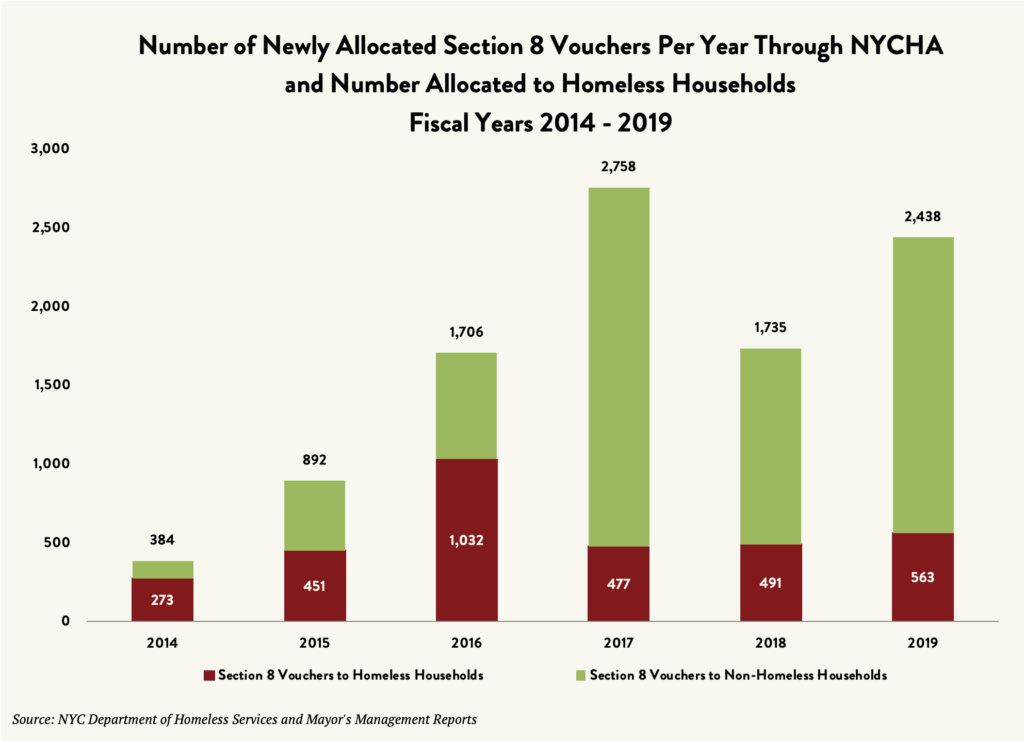

The City has created its patchwork of locally funded rent subsidies to make up for the lack of State and Federal assistance, which even in its limited supply has not been appropriately allocated to homeless New Yorkers. In 2019, fewer than 25 percent of available federally funded Section 8 vouchers were provided to homeless households – an appallingly low rate given the scope of the homelessness crisis. In 2016, 60 percent of available Section 8 vouchers went to homeless households.

The number and share of households moving out of shelters with City-funded subsidies increased between 2015 and 2019 despite insufficient State and Federal housing assistance. More households than ever are leaving shelters with some type of subsidy because the City has increased the availability of vouchers, including short-term ones like SOTA. The number of families moving out of shelters with State and Federal assistance has remained virtually unchanged since 2015.

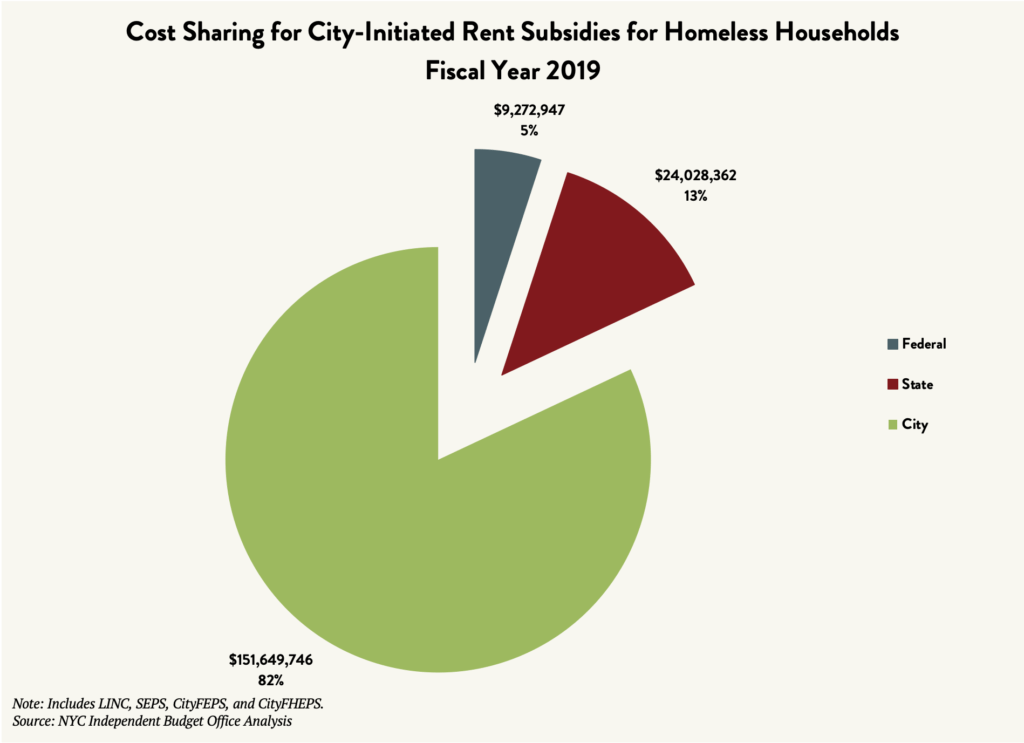

While the City has struggled to help families and individuals move into stable housing, the State has neglected its responsibility to provide housing assistance to homeless New Yorkers. In fiscal year 2019, the State contributed just 13 percent (about $24 million) of the cost of rent subsidies for homeless individuals and families. The City, conversely, paid 82 percent of the cost of rent subsidies ($152 million), more than six times the amount the State contributed. Since 2015, the State has never contributed more than 19 percent of the cost of local rent subsidies for homeless New Yorkers. [13]

HOUSING VOUCHERS AND STABILITY

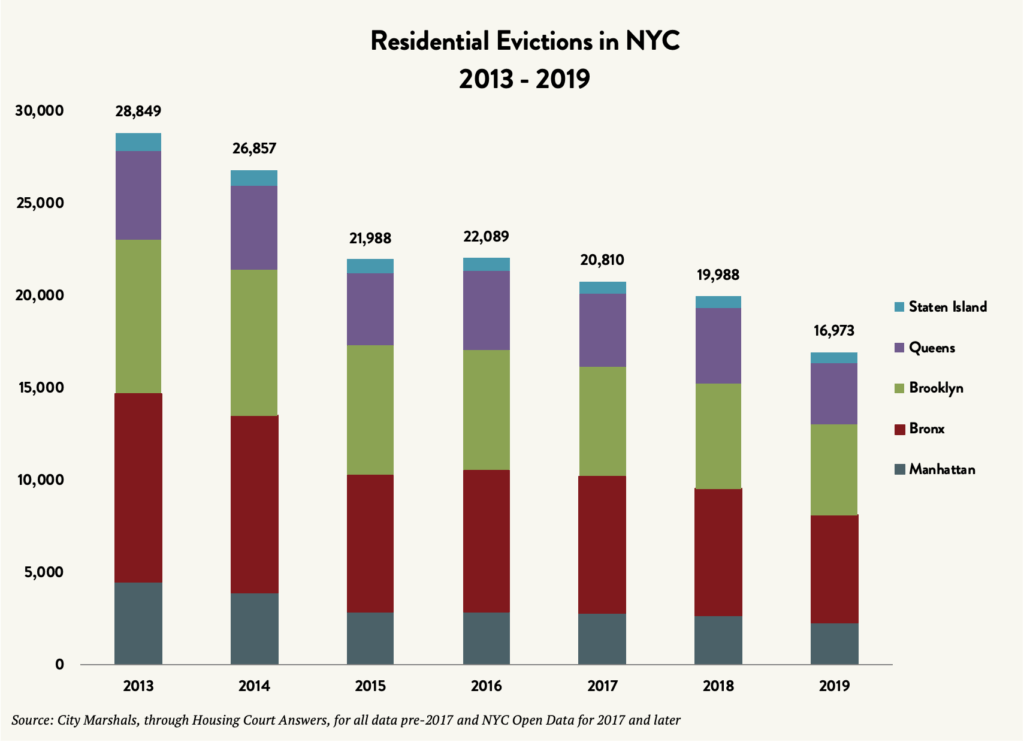

City: A- State: F

For the third year in a row, evictions in New York City are down. In 2019, residential evictions reached a new low of just under 17,000, down 41 percent from the high of 28,800 in 2013. Residential evictions decreased in every borough between 2018 and 2019. Queens saw the greatest percentage decline, with a 17-percent reduction, followed by Manhattan, with a 16-percent reduction.

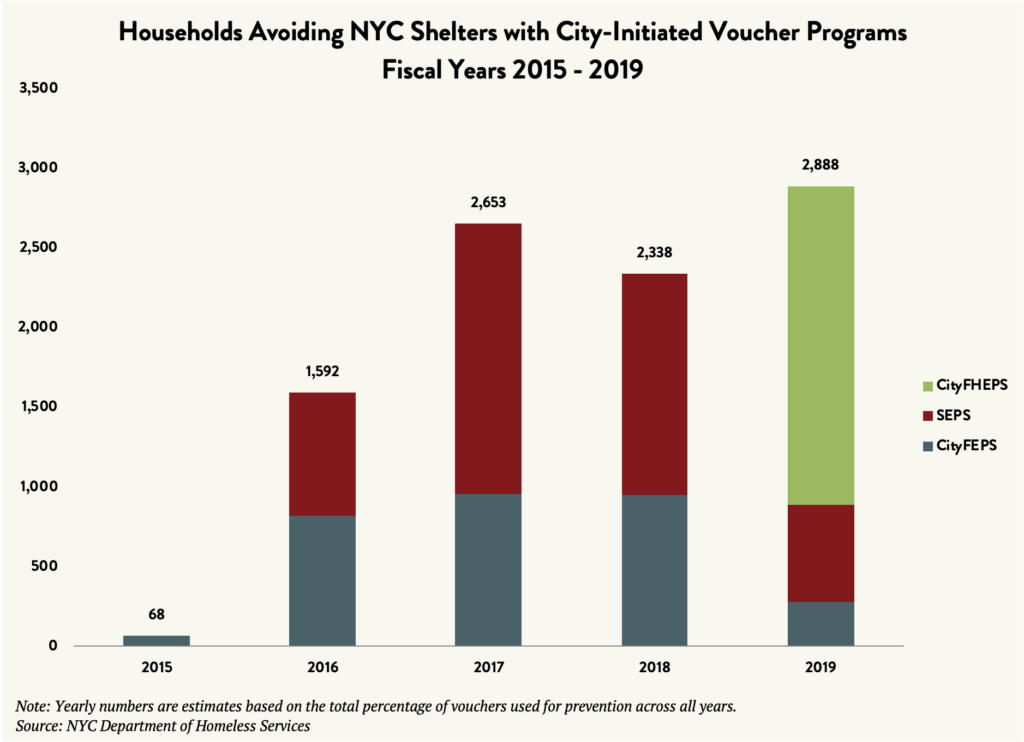

Key to the decline in residential evictions has been the City’s increased funding and distribution of rent arrears grants and the implementation of the right to counsel in housing court for low-income New Yorkers. In 2019, the City also helped nearly 2,900 households avoid shelters with the help of City-funded rent vouchers, up from 2,300 in 2018.

The State, meanwhile, has done little to help prevent homelessness, and instead has exacerbated the problem in New York City by regularly releasing people from prisons and other institutions directly to shelters without proper discharge planning (see page 10).

MEETING THE NEED FOR SHELTERS

City: C+ State: F

Cost

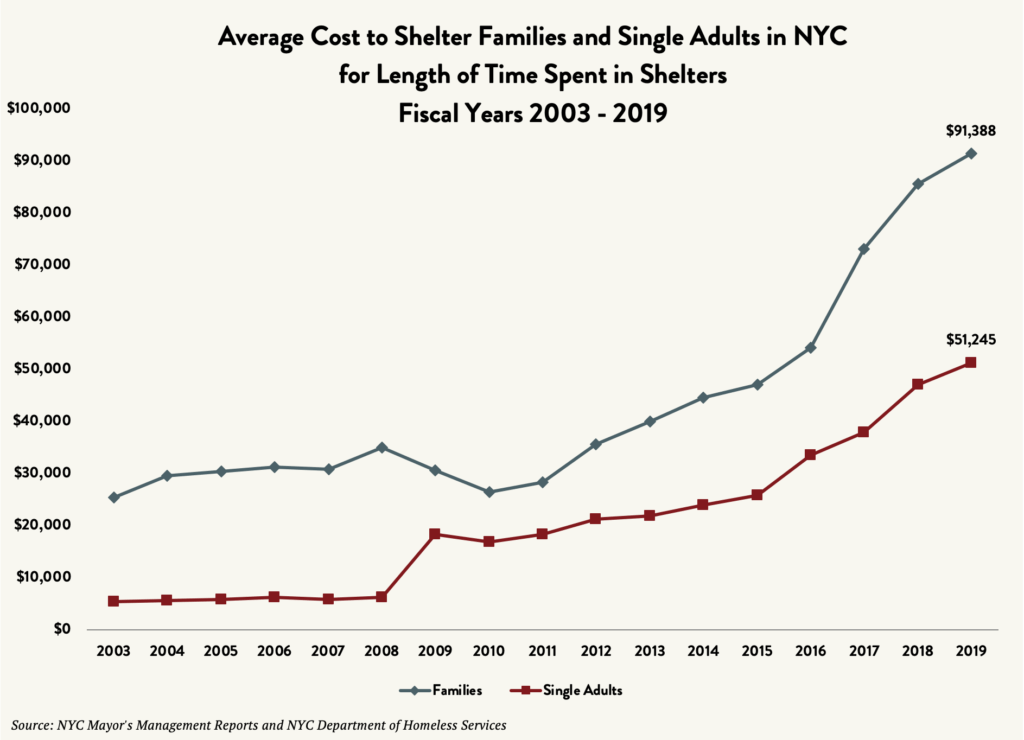

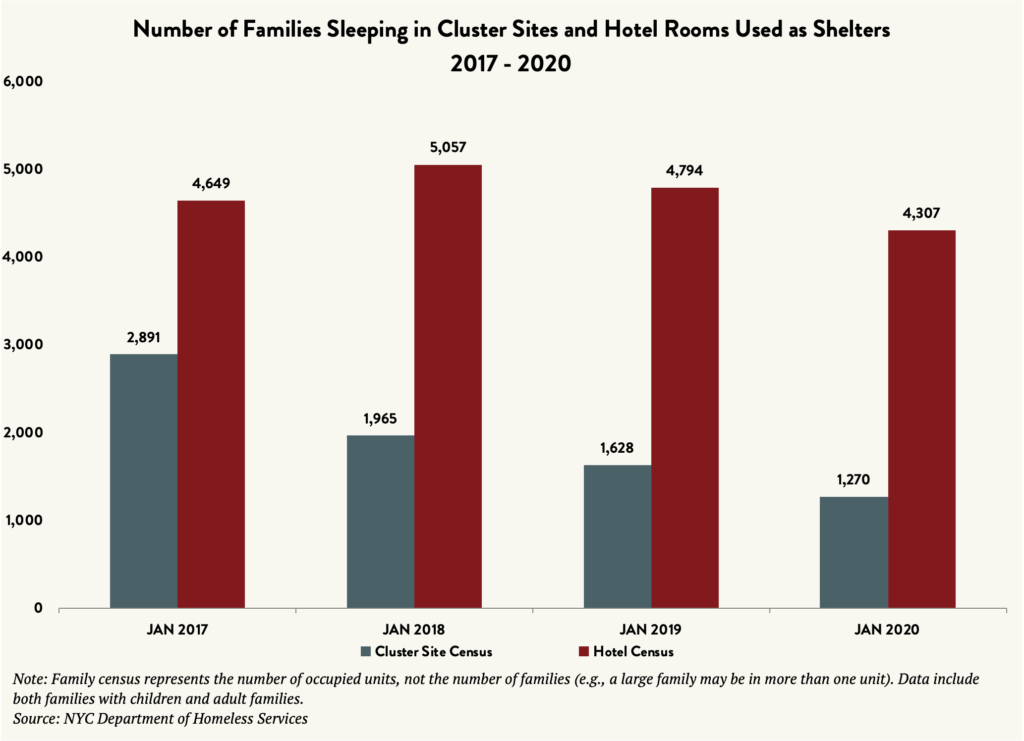

In fiscal year 2019, the cost of providing shelter to homeless families and single adults reached a new high. Accounting for the average length of stay, the cost to shelter one family exceeded $91,000 and the cost to shelter a single adult exceeded $51,000. Shelter costs have continued to rise because of multiple factors. For example, the City has made a commitment to standardize and right-size contracts among non-profit shelter providers, and has set budgets that more accurately reflect service costs. Yet the City is also still paying exorbitant sums to use commercial hotels as emergency shelters. On an average night in January 2020, more than 4,300 homeless families were sheltered in commercial hotels, representing about 30 percent of all family shelter accommodations. An additional 3,500 single adults were sheltered in commercial hotels – almost the exact number of individuals the State released directly to shelters from prisons in 2018. Notable, though, is the City’s progress in eliminating the use of cluster site shelters. Cluster site units now comprise just 9 percent of available family shelter placements, a reduction of 1,621 units between 2017 and 2020.

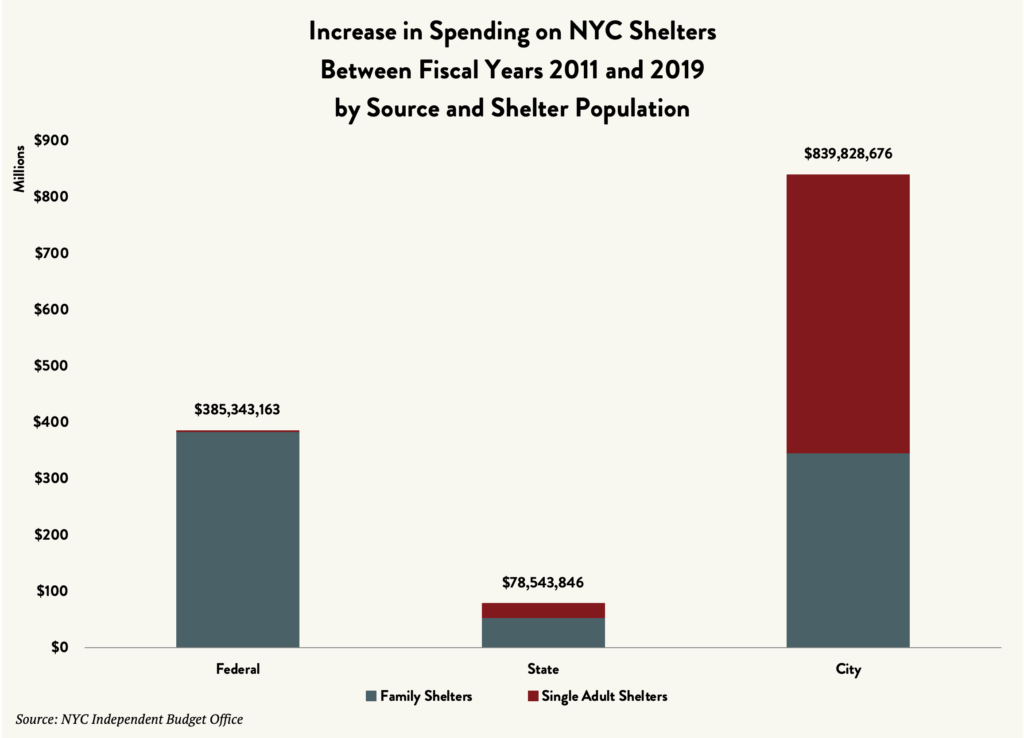

The State continues to fail to adequately contribute to the cost of shelters for homeless New Yorkers. In 2010 (the year before Governor Cuomo entered office), the State paid 27 percent of single adult shelter costs and 25 percent of family shelter costs, while the City paid 67 percent and 38 percent, respectively. In 2019, the State paid just 9 percent of both single adult and family shelter costs, while the City paid 88 percent and 42 percent, respectively. Between fiscal years 2011 and 2019, the City’s share of the cost of shelters increased by $840 million, due in large part to the increased cost to shelter single adults, while the State’s share increased by just $79 million.

Shelter Bed Availability

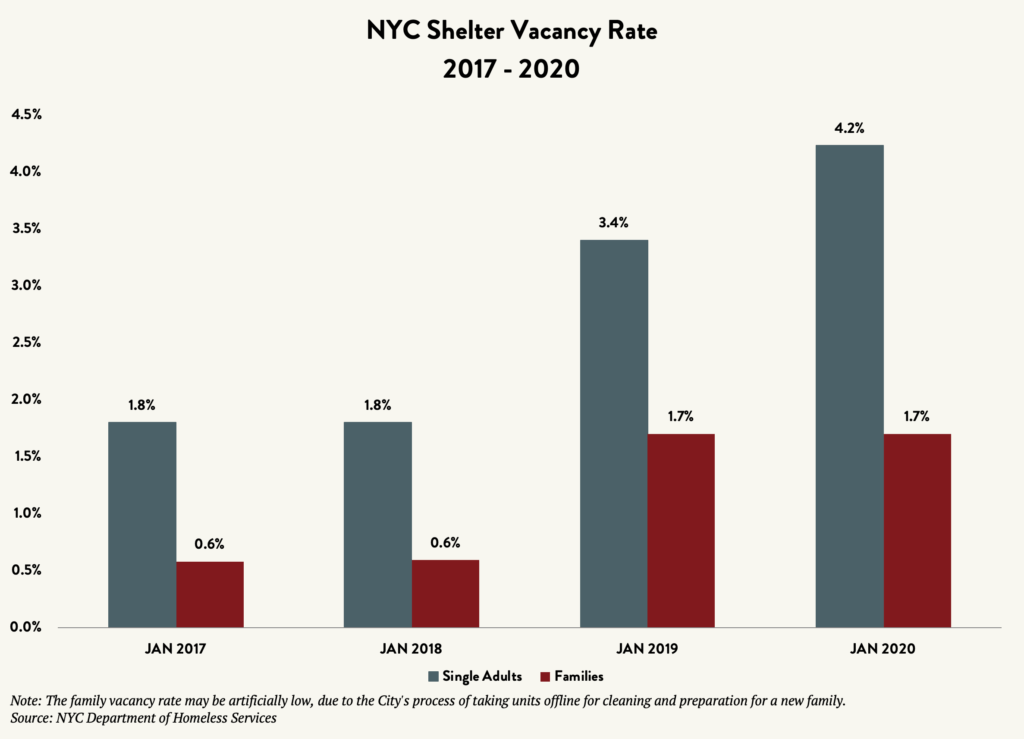

Over the past four years, the City has improved its planning to ensure it provides sufficient shelter capacity for homeless New Yorkers. In 2017, the City maintained an average vacancy rate in the single adult shelter system of just 1.8 percent, causing myriad problems with access to beds, involuntary transfers, long waits, and overall confusion and chaos for individuals entering shelters. Similarly, the vacancy rate for families in 2017 was just 0.6 percent, creating difficulty in placing families near children’s schools and parents’ support networks. Both vacancy metrics have improved considerably, with a single adult shelter vacancy rate for January 2020 of 4.2 percent and a family vacancy rate of 1.7 percent. Problems that accompany low shelter vacancy rates have thus decreased in frequency since 2017, although occasional problems do arise.

Snapshot of Shelter Conditions: Food

The Coalition for the Homeless receives frequent and widespread complaints about the food provided in shelters, including problems with the quality, preparation, handling, storage, and nutritional content, as well as accommodations to address dietary needs, food allergies, and religious requirements. Shelter residents, in their own words, describe the following food issues in shelters:

“If you are a vegetarian, there are only two options. You eat the same thing for lunch and dinner. Side dishes always run out. Given my health circumstances, a lot of food in the shelter may trigger medical issues. Even with a doctor’s referral, I cannot obtain my dietary needs. The shelter staff give you an attitude like ‘go buy something.’ They do not take responsibility for people like me, and diabetics have the biggest issues.” – K.C.

“It can be improved. There is always room for improvement in the shelter. I don’t know what the standards are. The food contains too much starch, and most of it is processed food. The food is giving us health issues. If you eat in the shelter, you will get sick. I was there 1.5 years, and you will get sick.” – Anonymous “

Where I am at, the food is terrible – prepackaged food, and for the most part it has no taste. It is like jail food. Small portions, and they say the portions are recommended for a meal. Sometimes they will give you two trays. Food is so terrible that they cannot give this stuff away. I don’t always eat it.” – Anonymous

“It is very bad. When they have something good, people eat it quickly. Sometimes the shelter cafeteria is open for 40 minutes and not for an hour. They do not give enough food. The portions are for kids. It is supposed to be ‘all-you-can-eat’ but they [the shelter staff] refuse. The lady says: ‘No, you cannot eat more.’ I went to eat at 7:00 pm for dinner, and the lady closed the gate and told me she was not going to give me food.” – E.B.

Below are examples of reports Coalition for the Homeless shelter monitors sent to the Department of Homeless Services regarding food issues we observed and complaints we received from shelter residents.

A July 2018 visit to Fort Washington Men’s Shelter resulted in this report to DHS:

We spoke to two clients who have food allergies that were not being accommodated. [CLIENT NAME] is allergic to seafood and tomatoes. He has a doctor’s letter, but is not offered any alternatives when those foods are provided. [CLIENT NAME] also has a doctor’s letter for food allergies, but reports no accommodations.

A March 2019 visit to Broadway House, a women’s shelter, resulted in this report to DHS:

The shelter has no vending machines and diabetic snacks are not available. Clients stated there is no alternative meal for those clients with allergies and other dietary restrictions. [CLIENT NAME] was in a diabetic coma for two weeks during 2018 because she could not access appropriate food. She spent a total of six weeks in the hospital.

A March 2019 visit to Jack Ryan Residence, a men’s shelter, resulted in this report to DHS:

The shelter has no vending machines and diabetic snacks are not available throughout the day. Clients complained that they are not permitted seconds at meal times. Instead, extra food is discarded. Clients wait outside the building so they can open the garbage bags and find the discarded food. Other clients beg for food on the streets. Clients complained that the breakfast hours are too limited. Elevator issues delay their arrival to the cafeteria.

A May 2019 visit to Casa de Cariño, a women’s shelter, resulted in this report to DHS:

Several clients expressed issues with the quality of the food. Several clients have reported having increased health issues since entering Casa de Cariño. One client reported that her diabetes medications have been tripled by her doctors since moving to Casa de Cariño in order to deal with the poor quality of the food that is served there. It was reported by more than one client that on several occasions meals were served by maintenance workers who do not have food handlers’ licenses.

MEETING THE NEEDS OF UNSHELTERED NEW YORKERS

City: C+ State: D

New Yorkers struggling to survive on the streets face increased criminalization through an array of new initiatives implemented by Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo. These new programs deploy NYPD, transit police, and other law enforcement officials to specifically target homeless individuals.

One recent and egregious example is the Subway Diversion Program, announced by the Mayor in June 2019. The program was framed as a way to offer services in lieu of contact with the criminal justice system to homeless individuals who bed down in the transit system, by having officers say that they will clear transit violation summonses if recipients agree to engage with street outreach teams. Unsurprisingly, in practice, the program unnecessarily increases contact between homeless people and law enforcement. First-hand reports from homeless individuals and observations of their interactions with the NYPD demonstrate that law enforcement officials explicitly target people who appear to be homeless, issuing summonses and then coercing individuals to board vans to travel to the offices of a shelter provider, all while promising that the summonses will be cleared if the person cooperates and accepts shelter and services.

At a New York City Council hearing on January 21, 2020, the NYPD testified that they had issued 1,296 summonses through this program and only 477 of those summonses had been cleared, meaning that a staggering 63 percent of summonses (819) issued through this program are still active. The homeless people who were issued these summonses likely cannot afford to pay them. We also learned that people who receive a summons are not eligible to have it cleared if they are already assigned to a shelter, Safe Haven, or drop-in center.

In August 2019, Governor Cuomo announced a plan similar to the Mayor’s Subway Diversion Program that directs MTA police and State officials to target homeless people at subway line endpoints. No additional funds for housing or low-threshold shelter beds were announced as part of this initiative. As of February 2020, there are no data on how many people have entered a shelter or been targeted, issued summonses, or arrested after contact with MTA police and State officials.

In December 2019, Mayor de Blasio finally heeded the calls of Coalition for the Homeless and other advocates when he announced a plan to provide additional housing and low-threshold shelters for homeless New Yorkers on the streets. The Journey Home plan promises an additional 1,000 Safe Haven shelter beds and 1,000 permanent apartments to be allocated based on a Housing First model. This is a step in the right direction, but still does not match the scale of the need for housing and other services, and does nothing to curb the increased criminalization of homeless people.

CONCLUSION

In the past four decades, mass homelessness has devastated the lives of countless New Yorkers. There is no dispute that the root of the crisis is the catastrophic lack of affordable housing for the lowest-income families and individuals, yet Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo have refused to enact policies that harness proven solutions to match the scale of the crisis, despite ample evidence supporting housing solutions. The problem is not one of resources or ideas; it is one of political will.

Governor Cuomo has been failing to address record homelessness in New York City, and the State in fact contributes substantially to the growing number of individuals sleeping in shelters through improper discharge planning and inadequate housing options for people leaving State-run institutions, including prisons and hospitals.

Mayor de Blasio, meanwhile, has a mixed record: His homelessness prevention initiatives are laudable, but insufficient in the absence of serious efforts to expand the housing supply for homeless New Yorkers on a scale to match the magnitude of the need.

Prospectively, Governor Cuomo must take meaningful action and advance solutions to end homelessness. First and foremost, he must immediately implement Home Stability Support (HSS), which will create a statewide rent subsidy that would bridge the difference between inadequate public assistance shelter allowances and actual rents for families and individuals who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. HSS will help homeless individuals and families access stable, long-term housing and result in a fairer distribution of cost-sharing between the City and State.

There is no criminal justice or policing solution to homelessness. It bears repeating that homelessness is not a crime. People avoid services and shelters for a variety of legitimate reasons, the most important being negative past experiences in the shelter system and other institutions, and bureaucracies that have repeatedly failed them. The vast majority of those bedding down in public spaces report a prior stay in the shelter system and contact with outreach teams since leaving the system. Because outreach workers are generally unable to provide anything more than another trip to a shelter, their offers of help are frequently rejected. Ending the tragedy of people taking makeshift refuge in transit facilities and on the trains requires giving homeless people somewhere better to go.

Urgent action is needed to expand the supply of permanent housing necessary to finally reduce homelessness, both for the New Yorkers on the streets and those in shelters.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

If Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo follow the below recommendations, the number of families and individuals sleeping in shelters each night would actually begin to decrease. By 2024, the total shelter census would decline by 32 percent and drop below 42,000 people for the first time since 2012. The number of homeless families would decrease by more than 5,000 households over the next four years, and the precipitous rise in homelessness among single adults would finally turn a corner. Detailed in the following pages are these recommended changes to housing production and placements, which would contribute to this projected reduction in the number of homeless individuals and families:

- Enacting Home Stability Support will add 4,000 housing placements with subsidies for households leaving shelters in the first year, and then slightly fewer each subsequent year as older, inadequate subsidies are subsumed over time. HSS will also help reduce the number of returning families and individuals who enter shelters by preventing displacement and fostering long-term housing stability for public assistance recipients

- Accelerating the pace of the State and City’s production of supportive housing from 15 to 10 years will add approximately 1,000 apartments per year.

- Increasing production of housing through HPD will add an additional 900 apartments per year.

- Increasing the percentage of Section 8 vouchers for homeless families and individuals could add an additional 1,500 vouchers per year.

- Reducing reliance on SOTA would decrease unstable, short-term housing placements for homeless families by at least 2,000.

Other recommendations to fund and expand housing for single adults and individuals leaving institutions could have an even greater impact on the shelter census and greatly reduce the tragedy of New Yorkers sleeping on the streets and in the subways.

HOUSING

Governor Cuomo must:

- Implement the Home Stability Support (HSS) program to create a State-funded, long-term rent subsidy for households receiving public assistance who are homeless or at risk of losing their housing due to eviction, domestic violence, or hazardous housing conditions.

- Accelerate the pace of production of the 20,000 units of supportive housing pledged by the Governor in 2016 by completing them within 10 rather than 15 years, and fully fund the construction and operation of the remaining 14,000 units.

- Follow the recommendations of the Bring it Home Campaign and adequately fund existing community based housing programs for individuals with psychiatric disabilities.

- Ensure effective reentry planning for individuals being released from State prisons in order to identify viable housing options prior to each individual’s scheduled release date.

- Reform punitive parole practices that allow parole officers to exercise wide discretion and deny placement at potentially viable addresses for individuals leaving State prisons.

- Fund the creation of supportive housing specifically for individuals reentering the community from State prisons.

- Expand the Disability Rent Increase Exemption program (DRIE) to include households with a family member with a disability who is not the eligible head of household.

Mayor de Blasio must:

- Allocate at least $20 million in the fiscal year 2021 budget to help subsidize the increased production of housing mandated under Local Law 19.

- Greatly reduce reliance on SOTA and help families move out of shelters with long-term rent subsidies, including Section 8 vouchers.

- Allocate at least three-quarters of tenant-based Section 8 vouchers made available each year to homeless households so they can exit shelters.

- Accelerate the timeline for the creation of 15,000 City-funded supportive housing units by scheduling their completion by 2025 rather than 2030.

- Create an impartial appeals process through the Human Resources Administration (HRA) for individuals applying for supportive housing.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo should together:

- Fund the production of more housing specifically for single adults, separate and apart from their respective existing supportive housing commitments.

- Expand access to supportive housing for adult families – a population with disproportionately high levels of disability and complex needs.

- Implement a system of notifying supportive housing residents of their rights as tenants and clients of service providers.

- Create a standard set of practices for supportive housing providers to interview and accept residents, with an emphasis on Housing First and low-barrier entry.

SHELTERS AND SERVING UNSHELTERED INDIVIDUALS

Mayor de Blasio must:

- Apply elements of the Safe Haven shelter model to general shelters to make them more humane, respectful, and suitable for homeless individuals whose past experiences lead them to avoid shelters.

- Ensure all shelters serve individuals and families with dignity, provide a safe environment, and are adequately staffed at all times to provide meaningful social services, housing search assistance, and physical as well as mental health care and/or referrals.

- Expand the supply of Safe Havens by at least 2,000 beds to meet the needs of unsheltered individuals bedding down on the streets and other places not meant for human habitation.

- Reform the provision of food in shelters to improve quality, expand oversight, adequately accommodate the nutritional needs of shelter residents, and allow for dietary, religious, and other requirements.

- End the Subway Diversion Program and CCTV monitoring of homeless individuals, and end the practice of deploying police officers to respond to the presence of homeless people on the subways and streets.

- Administratively clear all summonses that have been issued under the Subway Diversion Program.

Governor Cuomo must:

- Reverse harmful cuts to New York City’s emergency shelter system that have resulted in the State short-changing the City by hundreds of millions of dollars over the past six years, and share equally with the City in the non-Federal cost of sheltering families and individuals.

- Conduct oversight of hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions to prevent inappropriate discharges to shelters and the streets.

- Replace the grossly inadequate $45 per month personal needs allowance for those living in shelters with the standard basic needs allowance provided to public assistance recipients.

- Permanently eliminate the statewide requirement that shelter residents pay rent for shelter or enroll in a savings program as a condition of receiving shelter.

- Immediately end the initiative to place MTA police at the end of subway lines to target homeless individuals, and halt the plan to hire 500 additional MTA police officers, which will inevitably result in the disproportionate and discriminatory persecution of homeless and low-income New Yorkers, especially people of color.

Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo should together:

- Implement a less onerous shelter intake process for homeless families in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining necessary documents, 2) housing history documentation is limited to the prior six months, and 3) DHS-identified housing alternatives are investigated to confirm their availability, safety, and lack of risk to the potential host household’s tenancy. For adult families, the City must accept verification of time spent on the streets from the widest possible array of sources, including outreach workers, soup kitchens, social workers, health care providers, and neighbors.

- Fund additional services for individuals living with severe and persistent mental illnesses, such as expanding access to inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, providing mental health services in more single adult shelters, and adding more Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams for homeless people.

- Establish a structure to regulate, finance, and develop a medical respite program and longer-term residential supports to address the needs of individuals with medical conditions who are released from hospitals and other institutions, including those who may not have adequate documentation of their immigration status.

References

[1] The purpose of the Butler analysis, as outlined in the settlement, is for the City to determine the current and anticipated need for shelters for individuals and families with disabilities. This will inform the City’s plans to remediate existing shelter sites and appropriately plan for adequate accessible shelter capacity and services.

[2] Brad H. v. City of New York was filed in 1999 on behalf of incarcerated individuals on Rikers Island with mental illnesses. The lawsuit alleged a violation of plaintiffs’ constitutional rights in relation to inadequate discharge planning. The 2003 settlement requires the defendants to provide certain forms of discharge planning for incarcerated individuals who receive treatment for mental illness while in City jails. The terms of the settlement, which have been extended to July 31, 2020, require specific compliance monitoring, including releases from jails to shelters.

[3] The existence of a separate, youth-specific shelter system operated by the New York City Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) could account for some of the underrepresentation of youth in the DHS shelter system.

[4] Families with children and adult families (without minor children) must endure an onerous application process that requires that they prove their homelessness to the City. As part of the application, families with children must provide a two-year housing history and adult families must provide a one-year housing history. All families must document reasons why previous residences are no longer available or are unsafe for them. In November 2016, the State and City quietly agreed to modify a directive that governs which homeless families can qualify for a shelter placement. This new directive reversed earlier sensible improvements and has made it more difficult for homeless families to prove their eligibility

[5] See footnote 1 for explanation of Butler v. City of New York.

Press Coverage

New York Daily News: Advocates Slam Cuomo, de Blasio for Handling of City’s Homeless Crisis, which Hits Infants Hardest

WNYC: The Brian Lehrer Show: Homeless in a Pandemic

Politico New York: New York’s Leading Officials Receive Poor Marks for Enduring Homelessness Crisis

AMNewYork: One Percent of Children Born Last Year Went Home to a New York City Homeless Shelter: Report

Queens Daily Eagle: 1 in 100 Newborns Go From Hospital to Homeless Shelter

Take Action:

Call Governor Cuomo and tell him to include Home Stability Support in this year’s budget. This important legislation will help more New York families stay in their homes and help those currently experiencing homelessness transition into stable permanent housing.