State of the Homeless 2018

FATE OF A GENERATION:

How the City and State Can Tackle Homelessness by Bringing Housing Investment to Scale

By Giselle Routhier, Policy Director, Coalition for the Homeless

Executive Summary

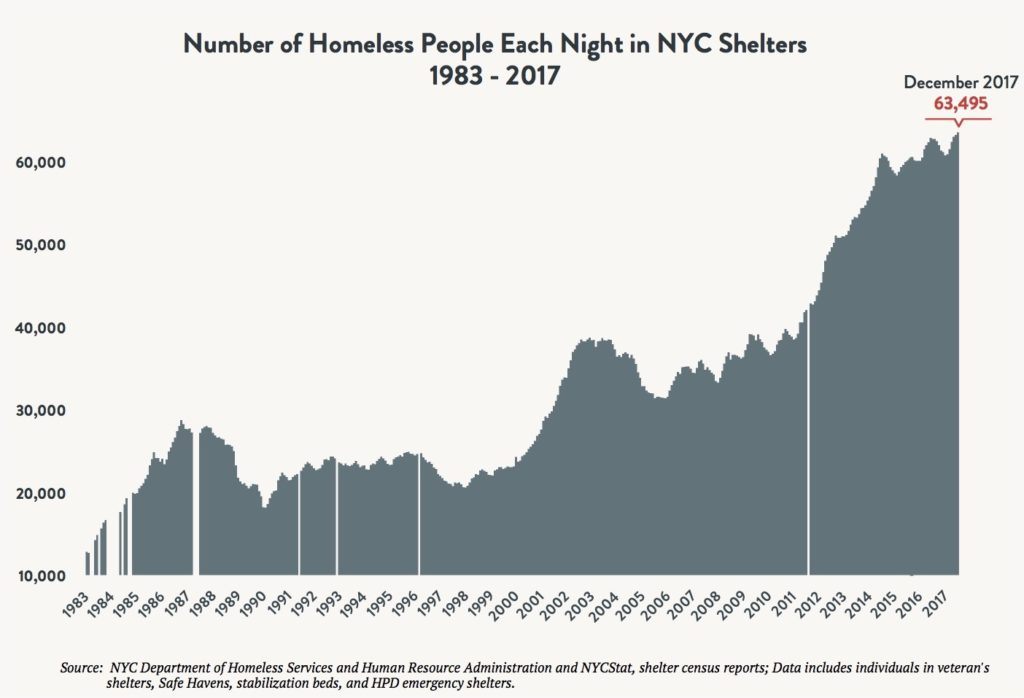

New York City reached a grim new milestone at the close of 2017: Last December, an average of 63,495 men, women, and children slept in City homeless shelters each night – an all-time record.[1] To put this in context, only nine cities in the entire state of New York have populations larger than New York City’s sheltered homeless population. Three-quarters of New Yorkers sleeping in shelters are members of homeless families, including 23,600 children. An 82 percent increase in homelessness over the past decade speaks to the severe shortage of affordable housing – fed by the combination of rising rents and stagnating incomes – along with devastating policy decisions that have limited access to affordable and supportive housing for homeless and extremely low-income New Yorkers.

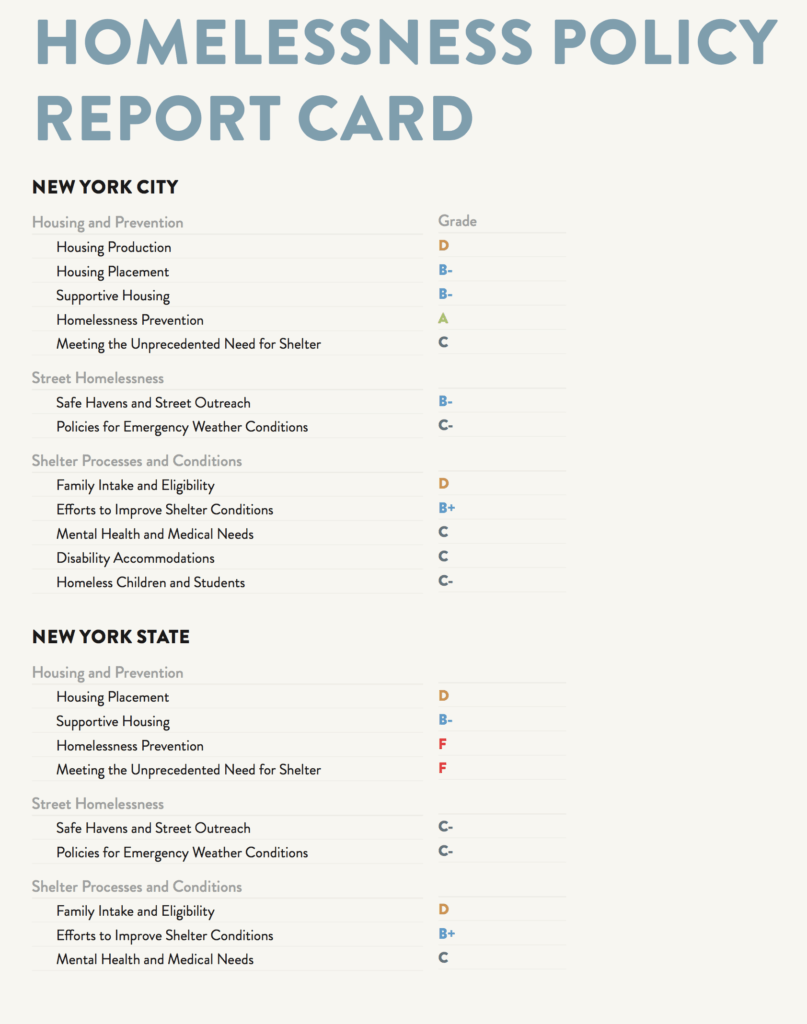

Both the City and State governments bear responsibility for the ongoing crisis. Mayor de Blasio’s record has been mixed and he has missed critical opportunities to meaningfully turn the tide on the problem he inherited, but which continues to grow on his watch. Governor Cuomo’s tenure has been marked by a systematic strategy of shifting costs to shelter and house homeless individuals from the State to the City. Aside from his commitment to supportive housing, which has yet to yield any units ready for occupancy, and some enhanced mental health services in shelters, his policies have been either woefully inadequate or concretely counterproductive. Our Homelessness Policy Report Card grades both the City and State on a range of policies needed to address the ongoing crisis.

As record homelessness remains a near-permanent fixture in our City, it is worth reflecting on how this tragedy impacts the tens of thousands of children that experience homelessness every single year.[2] A wealth of research confirms that homeless children perform worse on measures of academic achievement than their permanently housed peers and are also more likely to experience health problems and developmental delays. Nearly one in five homeless parents today was homeless as a child – and last year, more than 110,000 NYC students were homeless at some point. By allowing this crisis to continue, we are placing the fate of an entire generation at risk.[3]

The stark reality remains: The City and State cannot succeed in meaningfully reducing homelessness without taking bold steps to bring permanent housing solutions for homeless families and individuals to scale in response to the vast need. State of the Homeless 2018 articulates the steps necessary for the City and State to make a meaningful and lasting impact on this tragedy of historic proportions.

HOMELESS SHELTER CENSUS PROJECTION

By mid-2017, there were 60,700 homeless individuals sleeping each night in NYC shelters. Mayor de Blasio’s February 2017 plan, Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City, projects a mere 4 percent decrease in the number of people living in shelters by 2021.

Despite the Mayor’s projected decrease in the shelter census, at the end of 2017, an average of 63,495 men, women, and children slept in NYC shelters each night (see Chart 2) – an all-time record and a red flag highlighting the urgent need for adequate investments in housing built specifically to serve homeless New Yorkers.

If the City and State adopt the policy recommendations outlined below, the number of homeless people needing to sleep in shelters each night could be reduced by up to 35 percent, and by 2021, the census could be brought below 40,000 people per night for the first time in a decade.[4]

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

HOUSING

New York City must:

- Increase the number of units for homeless households created under the Housing New York 2.0 plan from 15,000 to 30,000, including 24,000 newly constructed, deeply subsidized units and 6,000 preservation units. This plan will require the Mayor to build roughly 2,000 new units of housing for homeless individuals and families every year between now and 2026.[5]

- Increase the number of Section 8 vouchers provided to homeless families from 500 to 2,000 per year.

- Increase the number of public housing placements for homeless families to 3,000 per year.

- Continue to house 4,500 new single adults and families per year through City-initiated rent subsidies.

- Accelerate the timeline for the creation of NYC 15/15 supportive housing units by scheduling their completion within 10 rather than 15 years.

- Establish a proper inspection protocol to guarantee that all housing placements made through NYCHA, Section 8, or City subsidies meet the needs of individuals and families; are guided by informed consent in all cases; and are free from conditions that could harm the health and safety of formerly homeless families and individuals or force them back into homelessness.

- Aggressively enforce the source-of-income anti-discrimination law.

- Provide all homeless individuals and families with housing application and search assistance.

New York State must:

- Implement Assembly Member Hevesi’s proposal to create a State-funded, long-term rent subsidy program known as Home Stability Support.

- Implement an anti-discrimination law that prevents source-of-income discrimination in all localities in New York State.

- Expand the Disability Rent Increase Exemption program (DRIE) to include households with a family member with a disability who is a child or an adult who is not the head of household. This would help such families retain their rent-stabilized housing, prevent their displacement to a system ill-equipped to meet their needs, and at the same time, prevent deregulation of their apartments.

- Accelerate the pace of production for the Governor’s 20,000 supportive housing units by scheduling their completion within 10 rather than 15 years.

- Adequately fund community-based housing programs for individuals with psychiatric disabilities, many of which have lost 40 percent to 70 percent of the value of their initial funding agreements due to inflation and inadequate investment by the State.

- Implement effective discharge planning for individuals being released from State prisons to identify viable housing options prior to each individual’s scheduled date of release.

The City and State together should:

- Ensure that individuals who have served their prison sentences receive all services they are entitled to and are not incarcerated for longer periods of time or otherwise held beyond their sentences because of lack of housing or shelter options.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

New York City must:

- Increase capacity in the shelter system to maintain a vacancy rate of no less than 3 percent at all times so that homeless New Yorkers are no longer effectively denied access to decent shelter that is appropriate to their needs.

- Place homeless families with children in shelters near children’s schools.

- Open additional Transitional Living Community (aka “TLC”) shelter capacity, which is designed to provide intensive services for homeless men and women with psychiatric disabilities.

- Shorten the timeframe for ending the use of cluster site shelters from the end of 2021 to the end of 2019.

- Change the temperature thresholds and durations for extreme weather “Code Blue” and “Code Red” policies, extend the time they are in operation to 24 hours, and prevent families from being served notices of ineligibility when extreme weather alerts are in effect.

- Develop a medical respite program to address the needs of individuals with acute medical conditions released from hospitals and other institutions who cannot be accommodated within the shelter system.

- Comply with the Butler settlement to accommodate the needs of individuals with disabilities.

- Require mental health training for all personnel assigned to mental health shelters and intake facilities.

- Ensure that all shelters are adequately staffed at all times.

- Initiate a spot-check monitoring protocol to better assess and address problem conditions in shelters.

- Eliminate the requirement that families applying for shelter must bring their children to their first appointment at intake, resulting in the children unnecessarily missing school.

New York State must:

- Reverse harmful cuts to NYC’s emergency shelter system that have resulted in the State short-changing the City $257 million over the past six years, and share equally with NYC in the non-Federal cost of sheltering families and individuals.

- Amend the cold weather emergency regulation to apply 24 hours per day, raise the temperature threshold, and prevent families from being served notices of ineligibility when the policy is in effect. Implement a “Code Red” policy that conforms to reasonable thresholds, applies 24 hours per day, and prevents families from being served notices of ineligibility when the policy is in effect.

- Establish a structure to license and regulate medical respite programs.

- Conduct oversight of all hospitals and nursing homes to prevent inappropriate discharges to shelters.

- Raise the personal needs allowance for those living in shelters to at least $144 per person per month, the same as others in Congregate Care Level 1 settings such as Family Care Homes and Family Type Homes for Adults.

The City and State together should:

- Implement a less onerous shelter intake process for homeless families in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining necessary documents, 2) the housing history documentation requirement is limited to a list of prior residences for six months, and 3) recommended housing alternatives are verified as actually available and pose no risks to the health and safety of applicants or to the continued tenancy of a potential host household.

RECORD HOMELESSNESS IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

MODERN MASS HOMELESSNESS IN ITS FOURTH DECADE

- At the end of 2017, an average of 63,495 men, women, and children slept in NYC homeless shelters each night. This is a new all-time high.

- The shelter census has increased 1 percent compared with the same point last year and 82 percent since 2007.

- In fiscal year 2017, an all-time record 129,803 unique individuals (including 45,242 children) spent at least one night in the shelter system – an increase of 57 percent since 2002.

- The steep and sustained increase in the shelter census that took place between 2011 and 2014 as a result of the previous mayoral administration’s elimination of all housing assistance programs for homeless families continues to contribute to ongoing record homelessness.

- Mayor de Blasio’s restoration of housing assistance for homeless families has slowed the rate of increase in the shelter census, but has not been aggressive enough to turn the tide: More families and individuals continue to enter shelters than exit to stable housing each year.

HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION

- Three-quarters of those sleeping in NYC shelters each night are members of homeless families.

- Nearly 40 percent of all individuals in shelters are children, and nearly half of them are under the age of six.

- A near-record number of families slept in shelters each night as 2017 ended: 15,568 households.

- The number of homeless children continues to remain below the all-time high of 25,849 reached in December 2014, but increased by 1,000 children over the second half of 2017 – to 23,655.

- The number of single adults in shelters continues to reach new records week after week, and now stands at more than 16,000 men and women – an increase of 9.5 percent in just the last year and 43.2 percent since Mayor de Blasio took office.

- The number of single adults in Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters hit new a record high 29 times between November 1, 2017 and January 31, 2018.

LENGTH OF STAY IN SHELTERS

- For the second year in a row, the average length of stay in shelters for all populations (single adults, families with children, and adult families) exceeded one year.

- The length of stay for families with children has stabilized, but it has not dipped below 400 days in the past five years.

- The average length of stay for single adults rose for the eighth year in a row and, at 397 days, is now 62 percent longer than it was in fiscal year 2010.

- Adult families continue to have the longest average length of stay – over 18 months – likely due to higher rates of disability among this population as well as fewer housing options for which they qualify and that meet their needs.

ECONOMIC CONDITIONS

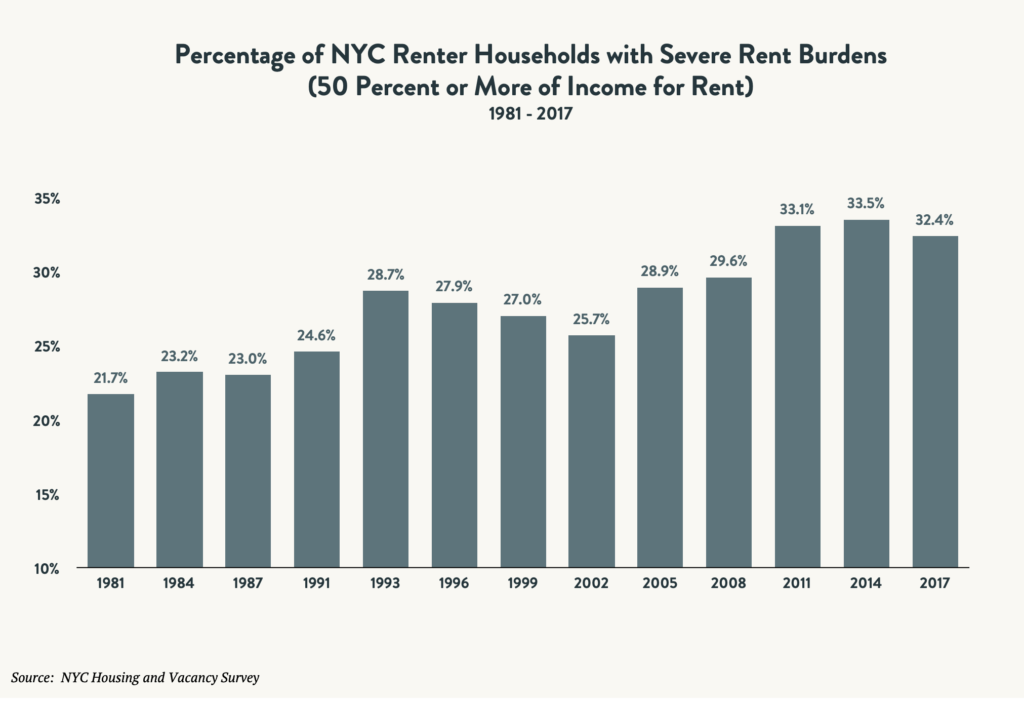

- Recently released data from the 2017 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey confirm that the affordability crisis and economic conditions that fuel record homelessness continued to worsen in recent years.

- Between 1996 and 2017, New York City lost more than 1.1 million housing units with contract rents below $800 per month. These low-rent apartments now comprise just 17 percent of all rental units, even as the need for them has not abated. In 2017, more than 860,000 households needed to spend less than $800 on rent in order for their apartment to be affordable (consuming 30 percent or less of income), but only 350,000 such apartments existed – a shortage of more than 510,000 apartments affordable to low-income families and individuals.

- As the overall citywide vacancy rate increased slightly in 2017 to 3.63 percent, the vacancy rate for low-rent units declined to just over 1 percent, and the vacancy rate for rent-stabilized units remained just above 2 percent. Vacancy rates for low-rent and rent-regulated apartments have been far lower than the rate for all rentals since 2005.

- Nearly one-third of NYC renter households are severely rent burdened, paying more than 50 percent of their income for rent.

- Nearly 5 percent of all renter households and nearly 6 percent of rent-regulated tenants lived in severely crowded conditions (more than 1.5 persons per room) in 2017.

HOMELESSNESS POLICY REPORT CARD

HOUSING AND PREVENTION

HOUSING PRODUCTION

City: D

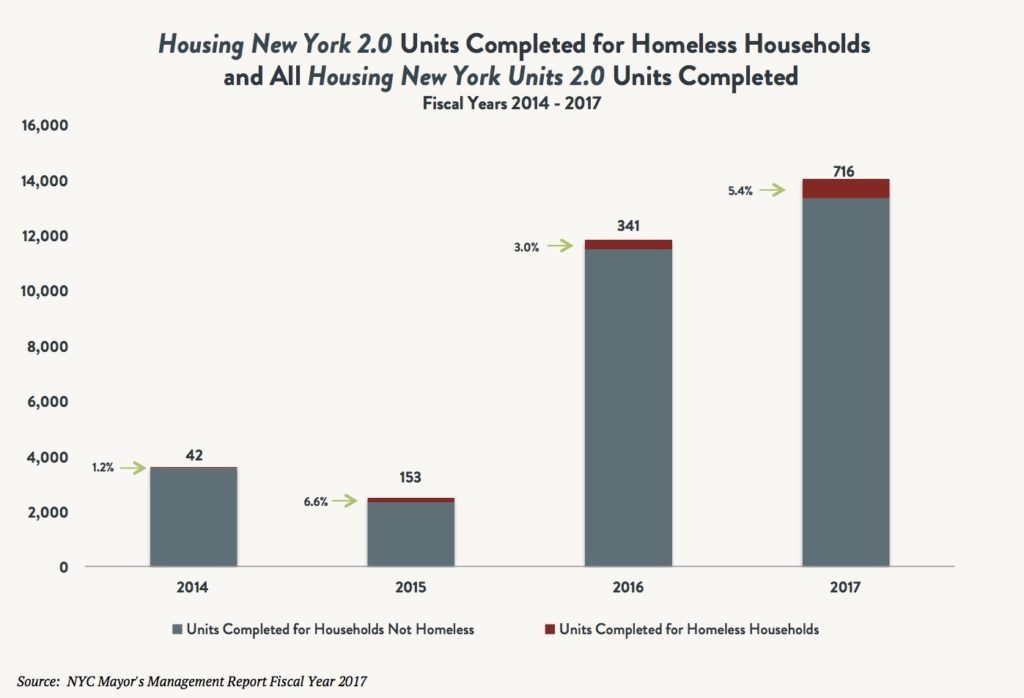

Mayor de Blasio has made one of his signature policy goals the unprecedented creation and preservation of 300,000 units of affordable housing, as outlined in his Housing New York 2.0 plan. However, he is planning to designate just 15,000 of these units for homeless households by 2026 – a paltry 5 percent.[6] In contrast, at a time when the shelter census was only a fraction of what it is today, Mayor Koch dedicated more than 10 percent of his overall housing plan to homeless adults and families, contributing to significant decreases in homelessness between the late 1980s and 1990s.

By the end of fiscal year 2017, nearly 32,000 units of housing were completed under the Mayor’s plan across the city, with another 46,000 units financed and in the early stages of development. Since the inception of the Mayor’s plan, only 1,200 of these units have been completed for homeless households – a mere 4 percent in four years. In fiscal year 2017 alone, only 700

units were created or preserved for homeless households, with fewer than half of those units available for immediate move-in by families and individuals from shelters. The remaining units were preserved, already-existing occupied units. Only about 3 percent of preservation units create a new housing opportunity for a homeless household in a given year. Despite ambitious goals, the Mayor’s housing production plan is not aligned with the reality of record homelessness, and the City is doing far too little to reduce homelessness among families and individuals.

HOUSING PLACEMENT

City: B-

State: D

Between 2006 and 2014 under Mayor Bloomberg, the City dramatically reduced the use of effective Federal housing resources, such as NYCHA public housing and Section 8 vouchers, to help homeless households move out of shelters – a disastrous policy that led to the steep increase in homelessness and a veritable “Lost Decade” for New Yorkers who had lost their homes. Mayor de Blasio has rightfully taken steps to reverse the damaging policies of this period by making these critical resources available once again to homeless New Yorkers. However, the accumulated deficit in housing placements continues to rise, as the number of public housing apartments and Section 8 vouchers made available to homeless households remains insufficient to make up for the Lost Decade and meet today’s unprecedented need.

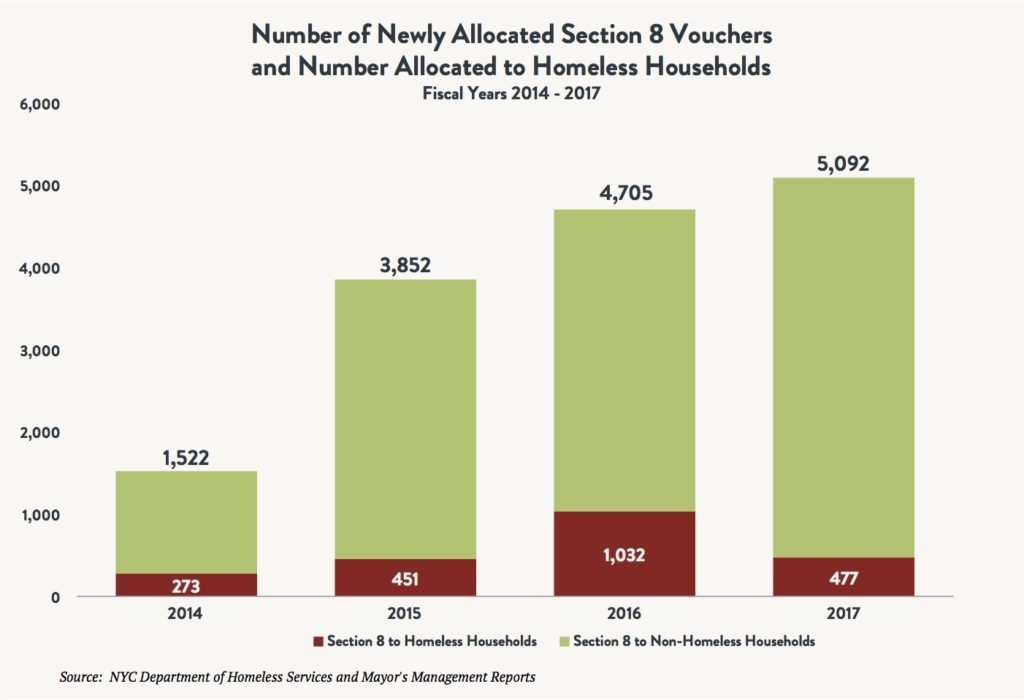

Although the number of families moving out of shelters to NYCHA public housing improved to 2,147 in fiscal year 2017 from 1,580 the previous year, it still remains below the Coalition’s recommended goal of 3,000 households per year. Moreover, fewer than 500 households moved out of shelters with the assistance of Section 8 vouchers, even though over 5,000 vouchers were made available to new households through NYCHA and HPD during the year – a steep decline in both the number and percentage provided to homeless households from fiscal year 2016. In other words, fewer than 10 percent of these critical Federally funded affordable housing vouchers were used to address record homelessness in our city last year. Had these Federally funded resources been consistently deployed to serve homeless families and individuals over the past decade, over 36,000 more households would have moved out of NYC shelters into stable, Federally subsidized homes, and far fewer would have returned to the shelter system from less stable housing (see Chart 20).

Mayor de Blasio’s new City-initiated rent subsidies continue to help roughly 4,500 families and adults move out of shelters each year. Four thousand additional households have used these subsidies to avoid homelessness since the inception of the programs. While the City’s progress in giving homeless New Yorkers a path out of shelters is commendable, the City must ensure that people are being placed into appropriate units. An alarming number of households have come to the Coalition for help after signing apartment leases through various City-funded programs (including LINC, SOTA, and the enhanced one-shot deal), only to find significant problems in the apartments. Many families had to return to the shelter system because of uninhabitable conditions in the apartments, including having no running water, inoperable stoves, and vermin – conditions that are particularly hazardous for children. Some families had no heat in their apartments in the middle of winter. In at least one instance, the apartment was deemed an illegal attic unit, which led the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development to issue a vacate order. Several families were moved into apartments in New Jersey, where they did not have any aftercare services or referrals to local advocacy or legal resources to assist them with their housing problems or reconnecting with disability-related services. The City must develop an adequate inspection process to ensure that individuals and families placed both inside and outside New York City move to habitable units and receive appropriate referrals to resolve any issues that may arise during their tenancies.[7]

The combined effects of Mayor de Blasio’s efforts to address homelessness are thus mixed – and in some areas they have been wholly inadequate, as reflected by indicators of housing stability among formerly homeless families and individuals. The number of stable placements for homeless families and single adults in 2017 remained roughly consistent with 2016, and still accounts for only 40 percent of family shelter exits and 26 percent of single adult shelter exits. Thus, the percentage of previously homeless families re-entering shelters did not decrease in 2017, but rose slightly to 49 percent, after decreasing three years in a row from a high of 63 percent (see Chart 20).

While the City’s housing placement efforts continue to fall short of what is needed to address the scale of the crisis, the State’s provision of housing assistance has been grossly inadequate. The State helps pay for only three of the 10 City-initiated rent subsidies – CityFEPS and LINC I and II – and in fiscal year 2018 will contribute only 17 percent toward the total cost of these programs, leaving the City to cover the bulk of the expenses. The State has also failed to release $15 million appropriated in each of the past three budgets to pay for rent subsidies for homeless households in New York City.

SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

City: B-

State: B-

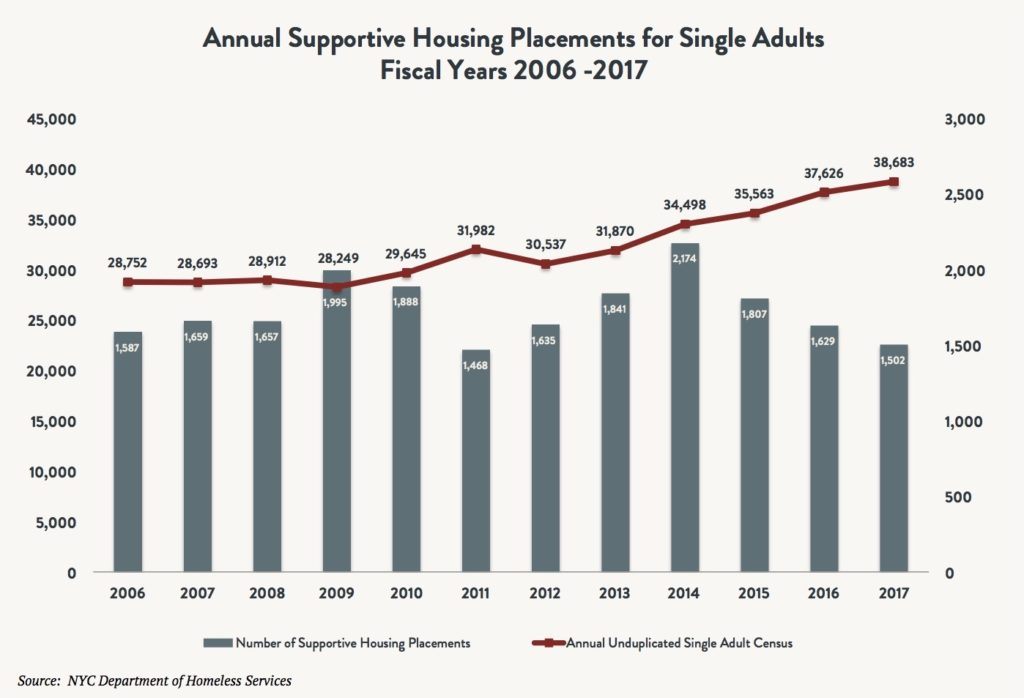

The number of homeless single adults placed in supportive housing reached a six-year low in fiscal year 2017. Just over 1,500 adults were placed in supportive housing – fewer than 4 percent of the total population of single adults in shelters in fiscal year 2017. This was the lowest proportion of shelter residents given supportive housing placements since 2006. In the 10-year period preceding 2017, there were an average 1,775 placements annually, and the shortage of placements has left hundreds of men and women to languish in shelters and on the streets awaiting their turn for supportive housing.

Despite the Mayor and Governor both making historic commitments in 2015 and 2016 to fund a combined 35,000 units of supportive housing, the production and occupancy of these units have been moving far too slowly. The City has so far opened only approximately 200 units of supportive housing under its NYC 15/15 commitment, despite the goal of opening over 500 units before the end of 2017. The State so far has opened none. All of the State’s promised 20,000 units will be new construction, and therefore not scheduled to open for several years. Both the City and State must accelerate the rate of production and occupancy for these critical housing resources, as the number of homeless single adults continues to skyrocket.

HOMELESSNESS PREVENTION

City: A

State: F

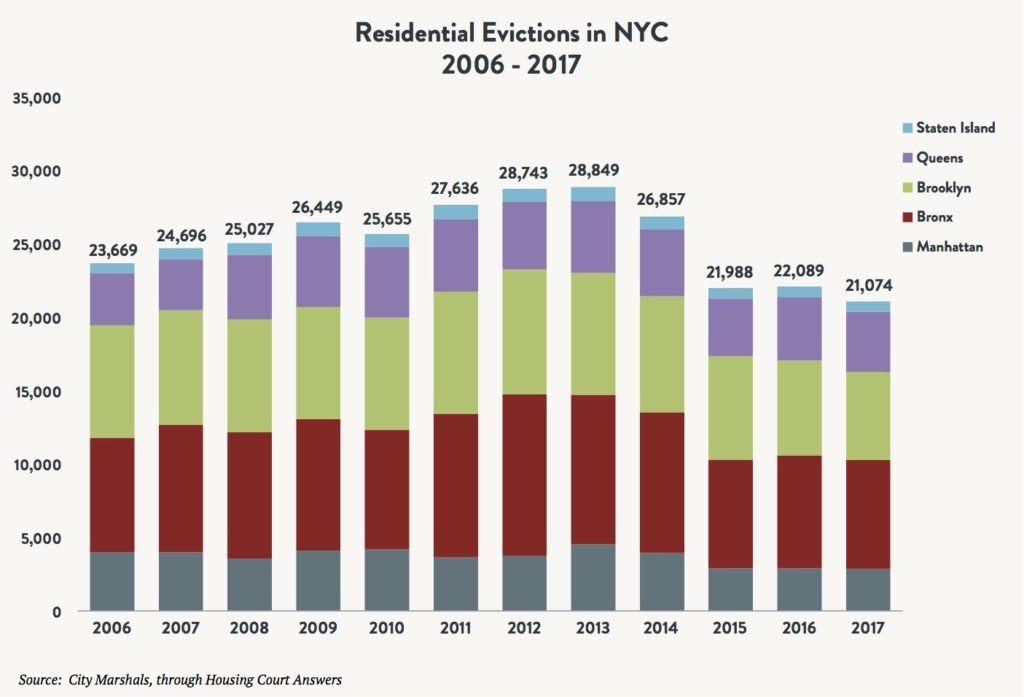

Since 2014, the City has made substantial investments in the provision of rent arrears grants and legal services for tenants in housing court, with approximately 180,000 New Yorkers [8] already having used expanded legal services. While eviction remains one of the main drivers of the city’s continuing homelessness crisis, the eviction prevention investments have prevented tens of thousands more New Yorkers from losing their homes. Residential evictions citywide reached a new low: just over 21,000 in 2017. This is the third year in a row in which evictions numbered between 21,000 and 22,000, after ranging between 25,000 and nearly 29,000 from 2008 through 2014. Since 2006, the largest percentage decrease in evictions occurred in Manhattan, at 29 percent, followed by Brooklyn, at 22 percent. All boroughs saw decreased evictions between 2016 and 2017.

This positive trend is likely to be reinforced following the passage in August 2017 of City Council Intro. 214-b – the right to counsel bill. The lack of legal representation for tenants in housing court has long served as one of the driving forces underlying the city’s high eviction rate, since unrepresented tenants often do not know their rights or how to access resources that could help them with rent arrears or other conflicts. Following a multiyear advocacy effort by the Coalition and other members of Right to Counsel NYC, the City has begun a five-year implementation to guarantee legal counsel in housing court for low-income tenants, and the program was initiated last fall in three high-need zip codes in each borough. Other cities across the country are already looking to replicate New York City’s groundbreaking model.

In addition to addressing the need for tenant representation in housing court, the City has also increased spending on rent arrears grants and expedited application processing to better help people who have fallen behind on their rent. A greater share of the City’s rent subsidy programs is being used for homelessness prevention as well: 25 percent of subsidies were used to help people stay in their own homes through mid-2017, up from 19 percent through December 2016. Paying off tenants’ arrears or connecting them to a voucher and thereby preventing them from becoming homeless is a fiscally sound investment and often costs a fraction of the $61,262 it costs per year to provide emergency shelter for a family.

In contrast, the State continues to contribute to record homelessness by allowing its correctional facilities to discharge parolees directly to New York City shelters rather than assisting them with adequate discharge planning and re-entry housing opportunities. Both the number and percentage of formerly incarcerated individuals released directly from State correctional facilities to NYC shelters rose dramatically between 2014 and 2017. More than 54 percent of all individuals released from prison to NYC were released directly to the shelter system in 2017 – up from 23 percent in 2014. More than 4,100 individuals were released to NYC shelters from upstate prisons in 2017, up 92 percent from 2014. One in five entrants to the shelter system now comes directly from a State prison, up from one in 10 just four years ago. This demonstrates an egregious failure by the State to conduct proper housing planning with incarcerated New Yorkers prior to prison discharge. It both fuels record homelessness in New York City and creates numerous additional obstacles for those already grappling with the formidable challenges of re-entry.

MEETING THE UNPRECEDENTED NEED FOR SHELTER

City: C

State: F

It now costs New York City more than it ever has to shelter homeless families and single adults. In fiscal year 2017, it cost on average $73,000 to provide emergency shelter to a family and $38,000 to provide emergency shelter to a single adult, given the average length of shelter stays for each population. Governor Cuomo’s budgeting practices have resulted in a massive withdrawal of State resources to address poverty and homelessness, and nowhere has the pain of these reductions been more keenly felt than in New York City. Between 2011 and 2017, the total cost to shelter homeless families increased by $552 million, but the State contributed just $26 million toward this increase (a paltry 5 percent), leaving the City to shoulder $266 million of the remainder not reimbursed with Federal funds. Likewise, the cost to provide shelter to homeless single adults increased by $327 million during the same period, with the State paying for just $26 million of the increase, Federal funds covering $1.8 million, and the City contributing $299 million. Thus, the State shortchanged the City in the amount of $257 million over these six years: That is the added amount the State would otherwise have provided for the rising cost of providing shelter had the increases not reimbursed with Federal funds been shared equally between the City and State.

While rents continue to rise and affordable housing remains in extremely short supply, the City continues to struggle to meet the growing need to provide shelter for single adults and families who have lost their homes. In January 2018, the City had fewer vacant beds in the shelter system for single adults than during the same month in the past two years. The vacancy rate was only 1.5 percent on any given night, and this caused an ongoing failure on the part of the City to accommodate individuals’ shelter placement needs and provide timely placement for newly homeless men and women coming into the shelter system.

As new capacity has been added to the shelter system for single adults in recent weeks, along with additional buses for transporting men and women to shelters, the placement problems have eased somewhat. But the shelter system for homeless single adults and for families will need to continue to grow until the City can meet its own goal of maintaining a 3 percent vacancy rate (the vacancy rate in the family shelter systems remains below 1 percent).

The most sustainable means available for reversing the relentlessly growing need for more shelter beds is, of course, to interrupt the cycle of homelessness through the development of an adequate supply of affordable and supportive housing to enable far more families and individuals to leave shelters for stable permanent homes.

STREET HOMELESSNESS

SAFE HAVENS AND STREET OUTREACH

City: B-

State: C

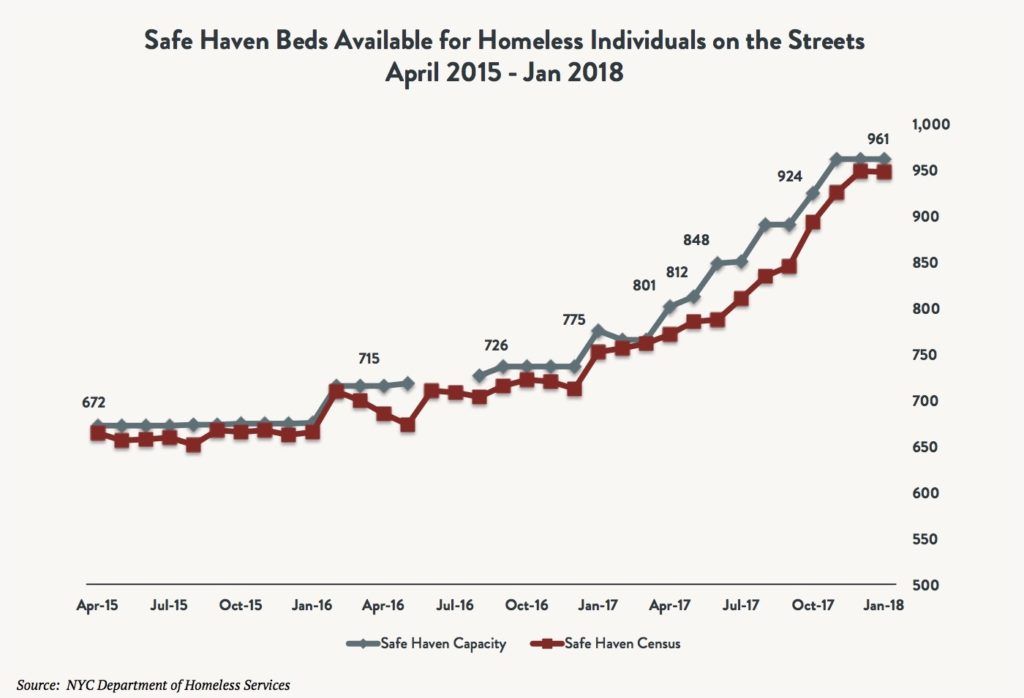

Thousands of vulnerable individuals continue to live on the city’s streets, in transportation terminals, and in other public spaces. Mayor de Blasio’s HOME-STAT initiative has ramped up outreach efforts and increased valuable low-threshold shelter capacity for vulnerable individuals living on the streets by 43 percent since 2015. As of January 2018, the City has moved nearly 1,300 individuals into shelters or other transitional housing and another 390 individuals into permanent housing. Low-threshold shelter resources like safe havens are critical for helping individuals come inside from the streets, and far more are needed to reach the thousands more individuals that continue to bed down on City streets, the majority of whom suffer with mental illnesses. This vast need, coupled with the insufficient number of appropriate shelter settings and permanent supportive housing units to meet the needs of individuals with mental illness, continues to fuel street homelessness in New York City.

Governor Cuomo, on the other hand, has repeatedly suggested changing the State mental hygiene law in order to effect the forcible detainment of homeless New Yorkers who may be reluctant to enter shelters from the streets. This proposal is extremely misguided and stands in direct opposition to evidence-based protocols for engaging individuals who are homeless and surviving on the streets.

PG is a 65-year-old native New Yorker with mental illness. He was forced to leave his former job prior to his planned retirement as a result of serious medical needs, and then approximately four years ago lost the home he had lived in for 20 years. Upon becoming homeless, PG entered the shelter system and was assigned to a shelter on Wards Island. He felt intimidated by the environment there and was distrustful of the system’s involvement in so many aspects of his life, so he decided not to return.

As a result, PG rides the subways and avoids street outreach teams at all costs. His small disability check is insufficient to pay for a room. He frequents soup kitchens all over the city, as well as a favorite senior center where he meets with friends and is able to stay warm on cold winter days. At night, though, he feels he has no choice but to sleep in subway stations or on the train to escape the cold. Although he describes this as the best of all available options, he says he is constantly harassed and arrested by the police. In a recent conversation, he remarked, “MTA police are really the problem – they harass us and take us to central booking just for sleeping. If you didn’t know better, you would think they were instructed to harass the homeless.”

POLICIES FOR EMERGENCY WEATHER CONDITIONS

City: C-

State: C-

“Code Blue” policies are intended to protect individuals and families from dangerous temperatures and weather conditions by easing access to shelters and drop-in centers and increasing street outreach. Unfortunately, once again, neither the City nor the State has implemented Code Blue policies that rationally

and effectively protect vulnerable New Yorkers from dangerous winter weather. Both City and State Code Blue policies rely on a 32-degree threshold, which is too low to adequately guard against weather-related health threats. Medical research shows that hypothermia can occur at temperatures well above 32 degrees, and those particularly susceptible to it include infants, the elderly, and those suffering from malnutrition, alcoholism, and endocrine disorders.[9] Low temperatures, wind, and damp weather endanger people exposed to the elements and can lead to cold weather injuries or even death due to hypothermia and frostbite.

Another fundamental flaw of the Code Blue policies is that they provide for protections and enhanced services only during nighttime hours. The City’s Code Blue policy takes effect after 4 p.m. and ceases at 8 a.m., regardless of daytime temperature or weather conditions such as heavy snow. The fact that Code Blue protections do not extend to daytime hours means families seeking shelter at either the Prevention Assistance and Temporary Housing (PATH) intake center or Adult Family Intake Center (AFIC) can be found ineligible during the day and turned away onto the below-freezing, snow-covered streets. This arbitrary daytime policy is enabled by the State’s own policy, which does not clearly require localities to make shelters available all day in inclement weather. If Code Blue policies are to actually ensure that men, women, and children are protected from the dangers of hypothermia and frostbite, they must specify a higher temperature threshold and require that shelters remain open and accessible at all times during dangerously cold weather conditions.

“Code Red” policies serve the same purpose, but for conditions of extreme heat. Similar to the City’s Code Blue policy, Code Red is only in effect for a certain portion of the day – in this case from noon to 8 p.m., unless the temperature threshold reaches 105 degrees for at least two hours. This, once again, places families at risk of being turned away from shelters during weather conditions that can be extremely hazardous, particularly for children, adults with health problems, and people taking certain medications. In addition, the temperature thresholds are extremely high: Code Red does not go into effect at all until the temperature reaches 95 degrees for at least six consecutive hours.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

FAMILY INTAKE AND ELIGIBILITY

City: D

State: D

The process families must undergo to access shelters in New York City is onerous, stressful, and error-prone. To apply, families must either go to the PATH intake center if they have children or the AFIC if they do not. The application process involves providing an array of documentation and undergoing extensive interviews and investigation, often with hours of waiting between each step. Families are given a 10-day conditional placement while their situation is investigated, and at the end of this conditional period they are found either ineligible or eligible, in which case they are given a more stable shelter placement. Sometimes, a seemingly small detail is enough for the City to deny shelter to a homeless family – for example, when a family has a few nights over the past two years for which they cannot prove where they slept.

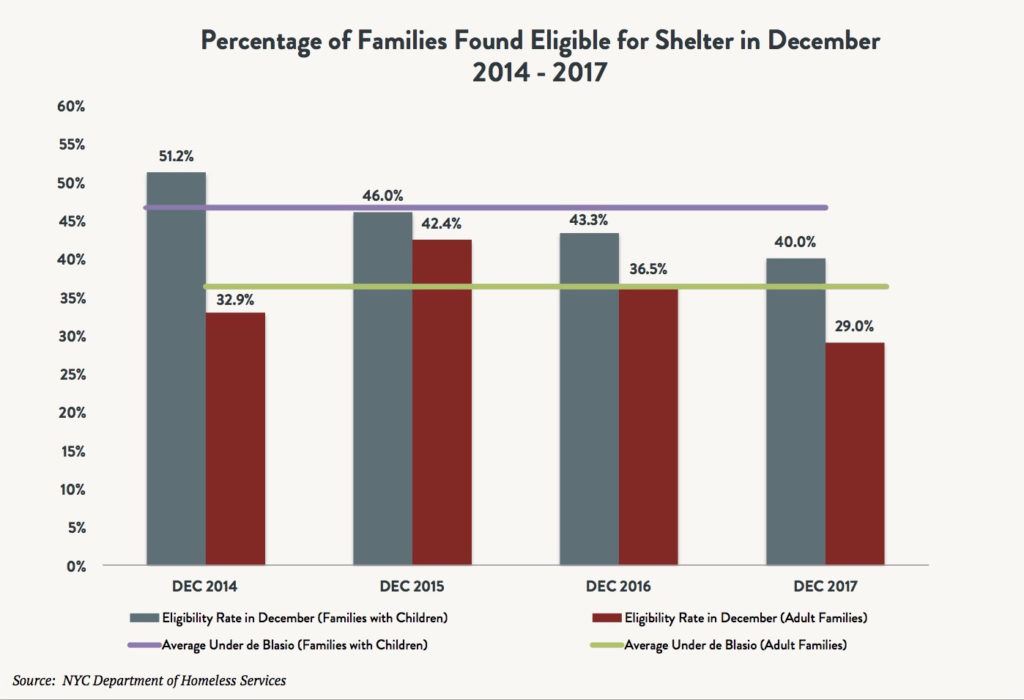

City investigators also turn families away at PATH and AFIC, and erroneously send them to housing that is not actually available to them – a scenario that has occurred with increasing frequency following a November 2016 agreement between the City and the State to modify a directive that governs shelter eligibility determinations. This policy change largely explains why the percentages of families with children and adult families found eligible for shelter continue to hover at the lowest levels of Mayor de Blasio’s tenure. In December 2017, just 40 percent of all families with children who applied for shelter were found eligible. In the same month, just 29 percent of adult families were found eligible. When a family is found ineligible but actually has nowhere else to go, they must repeat the arduous application process again, resulting in more paperwork, more stress, and more missed days of school and work. Some families spend nights sleeping on the subways, in emergency rooms, or elsewhere until they can make it back to the intake center or find an advocate to help them with their application. As the eligibility rate for families with children has decreased from over 53 percent in May 2016, the percentage of families forced to submit multiple applications before being found eligible has increased, reaching a high of 47 percent in June 2017, and surpassing 45 percent in three of the past seven months.

Although DHS no longer requires children to attend appointments at PATH when their parents are re-applying for shelter after having been denied, it still requires all family members to be present for an initial application, including school-aged children. No legitimate governmental purpose is served by this policy, which causes vulnerable children – who already face daunting odds and worse performance and attendance as a result of being homeless – to be unnecessarily removed from the one stable institution in their lives. Given that the whole family will report to a shelter at some point each evening, any necessary bureaucratic tasks requiring the physical presence of school-aged children can be accomplished then. The City should abolish this counterproductive requirement immediately.

EFFORTS TO IMPROVE SHELTER CONDITIONS

City: B+

State: B+

The City and State’s increased attention to shelter conditions has made a marked difference in the number of official violations recorded for each shelter. For all shelter types other than cluster sites, there have been significant decreases in the average number of violations per site since February 2016. All non-cluster site facilities now average fewer than 10 violations per site. Cluster sites continue to have the worst conditions, and the average number of violations per address rose from 45 to 60 between February 2016 and November 2017. However, an insufficient number of staff at many facilities, including both case management and maintenance staff, has resulted in the persistence of avoidable conditions, such as lack of regular cleaning and maintenance and delays in responding to individual complaints. Routine shelter condition complaints reported to the Coalition for the Homeless include: unsanitary facilities, mold, vermin, lack of heat, lack of ventilation, and poor quality food.

Although cluster sites continue to exhibit the worst conditions, the City is making significant efforts to stop using them to shelter families. Since February 2016, the City has stopped using at least 120 cluster site addresses. The City’s recently announced plan to convert an additional 30 addresses with 800 homeless families into permanent housing run by qualified non-profits is a substantial positive step toward reaching the goals of eliminating the use of cluster sites and replenishing the associated loss of rent-regulated apartments.

In its role as a regulatory authority for shelters, the State has been responsive to complaints about conditions and has substantially increased staffing to address the need for more frequent inspections of City shelters. It is in the process of implementing policies to certify all shelters, not just the larger facilities that have been regulated for decades.

MENTAL HEALTH AND MEDICAL NEEDS

City: C

State: C

The City’s right to shelter is an essential component of the safety net, but too often people with significant mental health or medical conditions are discharged from nursing homes and hospitals into shelters that are not equipped to meet their needs. Although the DHS system includes a small number of specialized shelters with some additional supports for people with mental health and medical needs, these facilities were never intended to serve as a replacement for nursing homes or hospitals for homeless people who cannot live independently.

In an effort to address the current gap in services for homeless people who are not medically appropriate for shelters but who do not need hospital-level care, the Coalition, government partners, other advocates, and health care providers have commenced discussions about the possibility of establishing new medical respite programs in New York City. These initial conversations are a promising step toward ensuring that the medical needs of homeless New Yorkers are appropriately and safely met. Pursuant to these ongoing discussions, the City must develop a medical respite program to address the needs of individuals with acute medical conditions released from hospitals and other institutions who cannot be accommodated within the shelter system, and the State must establish a regulatory structure to license any such respite programs in which the provision of bedside medical care is contemplated.

For homeless New Yorkers who are able to manage their mental health and medical needs independently within the shelter system, the shelters overseen by DHS may inadvertently exacerbate their underlying conditions. The needs of men and women are assessed when they enter the single adult shelter system, and they may be assigned to either a general population shelter or a specialized shelter, such as a facility for people with mental illnesses. The demand for beds in mental health shelters surpasses their availability, and therefore, the persistently low vacancy rate in the shelter system is disproportionately felt by clients assigned to mental health shelters. For example, from October 2017 through January 2018, there were 69 nights on which there were no reported vacant mental health beds for men, and 39 nights with no mental health vacancies for women. This often results in men and women with mental illness being bused around from shelter to shelter well into the night in search of a vacant bed – a stressful experience for anyone, but one that is particularly damaging for this vulnerable population who may be ill-equipped to deal with instability and bureaucratic barriers to a stable shelter placement. As required by law, the City must immediately add shelter beds that appropriately accommodate individuals with mental health needs, and ensure that such capacity meets individuals’ needs in the least restrictive setting possible and without segregating them from the rest of the sheltered population.

WH is diagnosed with schizophrenia, characterized by disorganized, illogical, and sometimes bizarre thoughts, in addition to a cognitive disability that makes keeping track of time or understanding the shelter system and its policies – like curfews – difficult for her to manage. As a result, she frequently loses her bed, and sometimes isn’t heard from for a few days after she is shuffled to a new shelter in an unfamiliar neighborhood. The shelter’s curfew policies are strict and inflexible with respect to signing for a bed at a specific time, despite WH’s difficulty keeping track of time and disorganized thoughts – challenges that are not uncommon among those living with serious mental illnesses.

On one occasion when WH lost her bed, the shelter could not find a vacancy in a mental health shelter for her. On each of five consecutive nights, she waited until 2 a.m. for a bed to open up at her assigned shelter, only then to be sent to a different shelter for the night. In the morning, she was awakened at 6 a.m. and told to return to her previously assigned shelter – where she would again wait in a chair all day and most of the night for a permanent shelter placement to be identified. This practice was the result of an unwritten policy of placing clients with mental health needs who had lost their beds only at mental health shelter sites (despite the fact that many such shelters are oversubscribed and rarely have vacant beds), instead of offering her the next available bed in any women’s shelter. This constant “over-nighting” was disorienting and exhausting for WH: It resulted in missed appointments and lost property as well as exacerbated mental health symptoms due to nightly sleep deprivation.

DISABILITY ACCOMMODATIONS

City: C

High rates of disabilities and health problems among homeless families and particularly among homeless individuals necessitate accommodations of various kinds, which for decades the shelter system failed to provide. In September 2017, the City reached a settlement in Butler v. City of New York, which was brought with the assistance of White & Case on behalf of clients of The Legal Aid Society, Coalition for the Homeless, and the Center for Independence of the Disabled in New York. The terms of the settlement mark a historic victory for homeless New Yorkers living with disabilities.

This agreement will require DHS to provide reasonable accommodations, cease discriminating against class members, communicate effectively with homeless people with disabilities, develop appropriate policies and procedures, properly train staff, identify and remediate barriers, and provide an appeals process for adverse determinations. As a result of the implementation of this agreement:

- Service animals will be accommodated;

- Shelter residents will receive services in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs;

- Every shelter will be assigned an Access and Functional Needs Coordinator;

- A menu of possible reasonable accommodations will be established; and

- Reasonable accommodation provision will be tracked.

Further, the stipulation’s baseline population and architectural analyses will inform the critically needed remediation plan to ensure geographically balanced, meaningful access to shelters and services for those with disabilities, and at the same time, avoid segregating them from others without disabilities. Implementation, however, will be an ongoing process phased in over five years.

Now, in the beginning stages of the implementation of the settlement, there remain many steep challenges for homeless people with disabilities sleeping in New York City shelters. One such issue is the availability of home care for single adults. While the City makes accommodations for families to receive home care when needed, they prohibit such services for single adults, citing privacy issues in dorm settings. Without access to needed home care services, single adults often rely on fellow shelter residents to help them with activities of daily living. Other examples of ongoing problems with disability accommodations include: a lack of assistance with understanding application documents; lack of cooking facilities for individuals with health conditions requiring special diets; lack of electrical outlets for various types of medical equipment; and shelter placements far from health care providers.

BR is a 45-year-old man who lost the use of his legs and much of the function of his arms in a car accident many years ago. He lives with his husband in an adult family shelter in Queens where he receives home care to assist with bathing, toileting, and dressing himself. As a result, he requires a physically accessible shelter placement that also affords him access to a private bathroom with accommodations such as a prescribed shower chair and sufficient space for his home health aide to be in the bathroom with him. BR’s doctors and other supports are located in Canarsie, and because his motorized chair often does not work, he cannot travel distances to access services. At the time Coalition staff met BR, only one shelter in the DHS system (the shelter in which he had been placed) could accommodate his needs. However, he was served a transfer notice due to a disagreement with his case manager and was set to be moved to a new location. His property was in the process of being bagged by shelter staff when he sought assistance from the Coalition. After speaking with his doctors and obtaining documentation

of his needs, Coalition staff managed to avert the transfer, and BR was able to remain in his accessible unit with the assignment of a new case manager.

UE is a single mother of three children (ages 2, 3, and 6), including TE, her 6-year-old child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. TE struggles with sensory perception, specifically with respect to his food, and is supposed to follow a special diet as a result. The family lives in a hotel room in Queens with two twin beds and no kitchen; there is inadequate space for the family to sleep and no way to meet TE’s dietary needs. He has refused to eat the prepared food provided by the shelter since first being admitted a few months ago, and so he has lost six pounds. All three children attend school in Queens, and TE is enrolled in a special school that includes transportation and a para-professional escort – important supports UE feels must be maintained. UE requested a transfer to another shelter unit in Queens to better accommodate her family’s needs. Although the request has been approved by DHS, she has received no feedback or update on the timing of her approved transfer for months.

HOMELESS CHILDREN AND STUDENTS

City: C-

The number of children who slept in a shelter at some point during the year has exceeded 45,000 for each of the past three years, and declined by less than 1 percent from 2016 to 2017. Homelessness carries particular stress for students, who struggle to keep up with their stably housed classmates. The City has continued to make insufficient progress in helping homeless children attend school regularly, despite increased resources to support bus routes between shelters and schools. The average school attendance rate for homeless students in shelters remained around 83 percent in fiscal year 2017 – equating to about a month of missed school days for homeless students. This ongoing attendance issue can be partly explained by the fact that the City has made no progress in placing more homeless families in shelters that are near the school of their youngest child. Only 50 percent of homeless families currently reside in shelters near their child’s school – down from 95 percent in 2005. As discussed above, DHS also requires school-aged children to miss school when their parents first apply for shelter. The City must immediately address the harmful disruption to the lives of homeless families and children caused by unnecessary missed school days.

In February 2017, Mayor de Blasio committed to keeping families closer to their communities of origin by shifting to a borough-based shelter system – a cornerstone of his Turning the Tide on Homelessness plan.[10] Delays in implementing this plan – coupled with the stubbornly high shelter census – have impeded the City’s ability to keep families close to their schools, churches, jobs, health care providers, and support networks. Sponsors of new shelters sited to enable families to remain closer to their communities of origin have encountered numerous hurdles, including vociferous neighborhood opposition.

Unfortunately, rather than denouncing the disturbing “not in my backyard” protests, in March 2017 the New York City Council added more fuel to the fire of shelter siting debates by introducing a package of ill-conceived bills to revise New York’s “fair share” rules – which affect how and where public facilities (like homeless shelters) are sited. The proposed bills would make shelter siting even more difficult, and impede progress toward the goal of placing homeless men, women, and children close to their schools and other familiar supports.

The number of homeless students in shelters (including those operated under the auspices of agencies other than the Department of Homeless Services) has reached another record high. More than 111,000 NYC students were homeless at some point during the 2016-17 school year – an increase of over 40,000 students since the 2011-12 school year, driven in large part by the continued increase in the number of students living in doubled-up situations. This increase reflects the growing number of precariously housed families, who will likely soon find themselves in need of homelessness prevention services or emergency shelter.

PROJECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

HOUSING

With family and single adult homelessness remaining at stubbornly high levels, the City and State must implement housing solutions on a scale to meet the magnitude of the need.

To help both homeless families and single adults, New York City must:

- Increase the number of units for homeless households created under the Housing New York 2.0 plan from 15,000 to 30,000, including 24,000 newly constructed, deeply subsidized units and 6,000 preservation units. This plan will require the Mayor to build roughly 2,000 new units of housing for homeless individuals and families every year between now and 2026.

- Continue to house 4,500 new single adults and families per year through City-initiated rent subsidies.

- Establish a proper inspection protocol to guarantee that all housing placements made through NYCHA, Section 8, or City subsidies meet the needs of individuals and families; are guided by informed consent in all cases; and are free from conditions that could harm the health and safety of formerly homeless families and individuals or force them back into homelessness.

- Aggressively enforce the source-of-income anti-discrimination law.

- Provide all homeless individuals and families with housing application and search assistance.And New York State must:

And New York State must:

- Implement Assembly Member Hevesi’s proposal to create a State-funded, long-term rent subsidy program known as Home Stability Support.

- Implement an anti-discrimination law that prevents source-of-income discrimination in all localities in New York State.

These actions, together with those listed below, will result in more families and individuals leaving the shelter system than entering it, and will begin to meaningfully reduce the shelter census far beyond Mayor de Blasio’s modest projections. The total number of homeless people needing shelter could be reduced by up to 35 percent from current levels, compared with the mere 4 percent decrease proposed in Mayor de Blasio’s plan, and the census could be brought below 40,000 people per night for the first time in a decade.[11]

To help homeless families, New York City must:

- Increase the number of Section 8 vouchers provided to homeless families from 500 to 2,000 per year.

- Increase the number of public housing placements for homeless families to 3,000 per year.

And New York State must:

- Expand the Disability Rent Increase Exemption program (DRIE) to include households with a family member with a disability who is a child or an adult who is not the head of household. This would help such families retain their rent-stabilized housing, prevent their displacement to a system ill-equipped to meet their needs, and at the same time, prevent deregulation of their apartments.

These actions, together with those listed above, would reduce the family shelter census by roughly 40 percent by 2021, compared with the roughly 13 percent decline projected by Mayor de Blasio.

To help single adults, New York City must:

- Accelerate the timeline for the creation of NYC 15/15 supportive housing units by scheduling their completion within 10 rather than 15 years.

And New York State must:

- Accelerate the pace of production for the Governor’s 20,000 supportive housing units by scheduling their completion within 10 rather than 15 years.

- Adequately fund community-based housing programs for individuals with psychiatric disabilities, many of which have lost 40 percent to 70 percent of the value of their initial funding agreements due to inflation and inadequate investment by the State.

- Implement effective discharge planning for individuals being released from State prisons to identify viable housing options prior to each individual’s scheduled date of release.

The City and State together should:

- Ensure that individuals who have served their prison sentences receive all services they are entitled to and are not incarcerated for longer periods of time or otherwise held beyond their sentences because of lack of housing or shelter options.

Mayor de Blasio’s current projections indicate that the single adult shelter census will reach 18,000 by 2021 – an astonishing two-fold increase in a decade. The above actions are absolutely critical to reverse this devastating trend. Taken altogether, our recommendations would result in a more beneficial, cost-effective 20 percent decline in the single adult shelter census by 2021.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

The City and State must also work together to improve shelter conditions and processes in order to reduce the trauma of homelessness for children, families, and adults.

New York City must:

- Increase capacity in the shelter system to maintain a vacancy rate of no less than 3 percent at all times so that homeless New Yorkers are no longer effectively denied access to decent shelter that is appropriate to their needs.

- Place homeless families with children in shelters near children’s schools.

- Open additional Transitional Living Community (aka “TLC”) shelter capacity, which is designed to provide intensive services for homeless men and women with psychiatric disabilities.

- Shorten the timeframe for ending the use of cluster site shelters from the end of 2021 to the end of 2019.

- Change the temperature thresholds and durations for extreme weather “Code Blue” and “Code Red” policies, extend the time they are in operation to 24 hours, and prevent families from being served notices of ineligibility when extreme weather alerts are in effect.

- Develop a medical respite program to address the needs of individuals with acute medical conditions released from hospitals and other institutions who cannot be accommodated within the shelter system.

- Comply with the Butler settlement to accommodate the needs of individuals with disabilities.

- Require mental health training for all personnel assigned to mental health shelters and intake facilities.

- Ensure that all shelters are adequately staffed at all times

- Initiate a spot-check monitoring protocol to better assess and address problem conditions in shelters.

- Eliminate the requirement that families applying for shelter must bring their children to their first appointment at intake, resulting in the children unnecessarily missing school.

New York State must:

- Reverse harmful cuts to NYC’s emergency shelter system that have resulted in the State short-changing the City $257 million over the past six years, and share equally with NYC in the non- Federal cost of sheltering families and individuals.

- Amend the cold weather emergency regulation to apply 24 hours per day, raise the temperature threshold, and prevent families from being served notices of ineligibility when the policy is in effect. Implement a “Code Red” policy that conforms to reasonable thresholds, applies 24 hours per day, and prevents families from being served notices of ineligibility when the policy is in effect.

- Establish a structure to license and regulate medical respite programs.

- Conduct oversight of all hospitals and nursing homes to prevent inappropriate discharges to shelters.

- Raise the personal needs allowance for those living in shelters to at least $144 per person per month, the same as others in Congregate Care Level 1 settings such as Family Care Homes and Family Type Homes for Adults.

The City and State together should:

- Implement a less onerous shelter intake process for homeless families in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining necessary documents, 2) the housing history documentation requirement is limited to a list of prior residences for six months, and 3) recommended housing alternatives are verified as actually available and pose no risks to the health and safety of applicants or to the continued tenancy of a potential host household.

References

[1] The Coalition reports on the number of homeless adults and children residing in the municipal shelter system, which is primarily administered by the NYC Department of Homeless Services. This does not include data about homeless people residing in other public and private shelters including: families and individuals residing in domestic violence shelters; runaway and homeless youth residing in youth shelters; homeless people living with HIV/AIDS residing in special emergency housing; homeless people residing in faith-based shelters; and homeless people sleeping overnight in drop-in centers. Our reports focus on the municipal shelter system because data for that system is historically consistent over three decades.

[2] Voiceless Victims: The Impact of Record Homelessness on Children

[3] NYC Department of Homeless Services. Profile of Families with Children in Shelter, April 2017.

[4] See [11] for full methodology.

[5] The City has already financed about 3,300 units of new construction.

[6] Preliminary Fiscal 2018 Mayor’s Management Report

[7] LINC: Living in Communities Rental Assistance Program; SEPS: Special Exit and Prevention Supplement; CityFEPS: City Family Eviction Prevention Supplement; HOME TBRA: Home Tenant-Based Rental Assistance; SOTA: Special One-Time Assistance. For more information about individual City subsidy programs, see: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dhs/permanency/rental-assistance.page

[8] De Blasio Administration Reports Record 27% Decrease in Evictions as Access to Legal Assistance for Low-Income New Yorkers in Housing Court Increases: http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/065-18/de-blasio-administration-reports-record-27-decrease-evictions- access-legal-assistance-for

[9] Source: O’Connell, J., Petrella, D., Regan, R. (2004). Accidental Hypothermia and Frostbite: Cold-Related Conditions. The Health Care of Homeless Persons: A Manual of Communicable Diseases & Common Problems in Shelters & on the Streets, published by Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

See also: Biem, J., Koehncke, N., Classen, D., Dosman, J. (2003) Out of the cold: management of hypothermia and frostbite.

[10] Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City

[11] Methodology for the following projection graphs is as follows: The Mayor’s plan, Turning the Tide on Homelessness in NYC, projects that the total shelter census will decrease by 2,500 people over five years. This reduction is a combination of a reduction in the family shelter census that counteracts a predicted increase in the number of homeless single adults sleeping in shelters. The Mayor’s plan assumes that “the single adult census will increase at about the annual rate it has increased over the past decade.” At the current rate, the single adult shelter census will rise by approximately 3,000 people in five years. Therefore, the family census must decrease by 5,500 people in five years to account for the total projected shelter census decline of 2,500 over five years. This report assumes an average family size of three, consistent with City assumptions. This report also assumes the reduction will be spread out evenly over five years. Coalition for the Homeless projections are based on assumptions about the number of families and single adults entering and leaving shelters. Exits from shelters to stable housing placements will increase by the amounts recommended in our report and entries to shelters will decrease slightly as a result of reduced housing instability and returns to the shelter system. The number of shelter residents exiting without subsidies is projected to be similar to years when a greater number of stable housing options were available.

Press Coverage

New York Daily News: Population At City Homeless Shelters Hits Record High Of 63,495, Study Shows

NY1: Report: Number of Homeless in City Shelters at Record High

El Diario NY: Sube Como Nunca El Número De Neoyorquinos Durmiendo En Refugios

PoliticoPro: Report Cites City And State Policy Failures On Homelessness

6SqFt: NYC’s Homeless Shelter Population Would Make It the 10th Largest City in the State

TV/Radio

WNBC-NY: Coalition for the Homeless Says the Number of People Relying on City Shelters has Now Reached an All-Time High

NY1: Occupancy at City Homeless Shelters Hit an All-Time High Last Year

1010 WINS News: Homelessness in the City is at Record Highs

WNYC: A New Report Says Over 63,000 Men, Women, and Children in New York City are Sleeping in Shelters Every Night

NPR: City’s Shelter Population Has Increased by 79% in the Last Decade

Take Action:

Sign our petition to urge Mayor de Blasio to dedicate 30,000 units of permanent housing to homeless New Yorkers!