State of the Homeless 2017

REJECTING LOW EXPECTATIONS:

Housing is the Answer

By Giselle Routhier, Policy Director, Coalition for the Homeless

Executive Summary

New York City remains in the midst of the worst crisis of homelessness since the Great Depression, with more than 62,000 men, women, and children sleeping in shelters each night. A chronic shortage of affordable housing and the potent combination of rising rents and stagnant wages have fueled a daunting and unabated 79 percent increase in the demand for shelter in the last decade. Three-quarters of New Yorkers staying in shelters are within families, and children constitute an alarming 38 percent of all those in shelters. There is no question that the City and State can implement solutions that work, but in order to match the unprecedented need, they must both accelerate and bring to scale their respective affordable and supportive housing production pipelines.

Although Mayor de Blasio has stabilized the shelter census with substantial investments in homelessness prevention and by helping thousands of families and individuals move into homes of their own through a variety of rent subsidy programs and stable Federally-funded apartments, the magnitude of the crisis requires much more. Extreme income inequality and unanticipated but rapid growth in New York City’s population together are pushing New Yorkers at the lowest end of the income spectrum out of the housing market entirely. City and State housing programs have proved insufficient to keep pace with the extreme need and enable more of the poorest individuals and families to keep their homes or reenter the rental market. Although homeless families and individuals have access to an array of City rent subsidy programs, the average length of stay in shelters for every segment of the homeless population exceeds a year as they grapple with the same scarcity of affordable housing that led many into the shelter system to begin with.

The stark reality is this: The City cannot succeed in turning the tide and achieving meaningful reductions in homelessness until it 1) fully utilizes all of its existing housing resources, including increasing stable housing placements in NYCHA and HPD to 5,500 per year for families, as well as 5,000 rent subsidies and supported placements for single adults, and 2) creates a new capital development program to finance construction of at least 10,000 units of affordable housing for homeless households over the next five years.

The City cannot combat homelessness on its own: The State must fully partner with the City to address the crisis. At a time of record need, the State has greatly and inexcusably reduced its proportional contributions to the shared cost of providing shelter to homeless New Yorkers, while simultaneously delaying the release of funds for desperately needed supportive and affordable housing that would enable them to move out of shelters and into permanent homes.

Record homelessness has strained the shelter system, exacerbating longstanding problems such as arduous intake procedures, hazardous conditions, insufficient accommodations for people with mental and physical disabilities, flawed code blue policies that fail to protect homeless people from dangerous cold weather, and the placement of families in shelters far from their schools and other social supports. These significant problems must be addressed, but at this critical juncture, the principal focus of City and State homeless policy must be on rapidly reducing the need for shelters by bringing permanent housing solutions for families and individuals to scale.

The structural forces contributing to record mass homelessness are formidable, but the human and financial costs of failing to tackle the crisis are far too great, and City and State responses have proved anemic at best. Just as the City and State partnered together in the late 1980s and 1990s to finance supportive and affordable housing on an unprecedented scale, so they must once again. While they work to fix the harmful processes and conditions in the shelter system, both the City and State need to accelerate and expand supportive and affordable housing production to provide homes for homeless New Yorkers and to rectify the dearth of affordable housing that has pushed tens of thousands of New Yorkers into homelessness.

HOMELESS SHELTER CENSUS PROJECTION

- At the end of fiscal year 2016, there were 60,000 homeless individuals staying each night in NYC

shelters.

- Mayor de Blasio’s recent plan, Turning the Tide on Homelessness in New York City, would produce

only a nominal decrease in the number of people living in shelters by 2021.

- If the City and State adopt the policy recommendations outlined below, the number of homeless

people needing shelter each night could be reduced by up to 25 percent, and bring the census

below 50,000 people per night by 2020, while the Mayor’s plan would by this point have only

reduced homelessness by 3 percent.[1]

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

HOUSING

With family and single adult homelessness remaining stubbornly at record levels, the City and State must invest in housing solutions on a scale to meet the magnitude of the need.

New York City must immediately:

- Increase the number of public housing placements for homeless families from 1,500 per year to at least 3,000 and the number of Section 8 and HPD resources to at least 2,500 placements. At least 5,500 placements per year are needed to regain the ground lost as a result of the 32,000 placements denied to homeless families during the “Lost Decade.”

- Continue to place at least 3,000 families through City-funded rent subsidy programs each year.

- Quickly open new units of supportive housing under the Mayor’s 15-year, 15,000-unit

commitment.

- Significantly increase the number of single adults provided with rental assistance or supported

housing to at least 5,000 per year.

- Create a new capital development program to finance at least 10,000 units of affordable housing

for homeless households over the next five years.

- Aggressively enforce the source-of-income anti-discrimination law with landlords who illegally

reject families and individuals seeking to use housing vouchers to help pay their rent.

- Provide all homeless individuals and families with housing application and housing search

assistance, including all individuals and families placed in hotels and cluster site apartments.

New York State must immediately:

- Release the $1.9 billion for affordable and supportive housing funds appropriated in 2016 and

currently stalled due to inaction by the Governor and Legislative leaders. - Implement Assembly Member Hevesi’s proposal to create a State-funded long-term rent subsidy

program, known as Home Stability Support. - Expand the Disability Rent Increase Exemption (DRIE) program to include households with a

family member with a disability who is a child or an adult but is not the head of household.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

The City and State must also improve shelter conditions and processes in order to reduce the trauma of homelessness for families, children, and single adults; provide lawful accommodations for people with disabilities; reduce the length of shelter stays; and reduce overall disruption for homeless children and students.

New York City must:

- Open additional Transitional Living Community (aka “TLC”) shelter capacity – designed to provide intensive services to help people with psychiatric disabilities develop independent living skills – for homeless men with such needs.

New York State must immediately:

- Reverse harmful cuts to New York City’s emergency shelter system, and share equally with New York City in the non-Federal cost of sheltering homeless families and individuals.

The City and State together should implement:

- A less onerous shelter intake process, in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining required documents, 2) the housing history documentation requirement is limited to a list of residences for six months, and 3) recommended housing alternatives are verified as actually available and pose no risks to the health and safety of applicants or the continued tenancy of a potential host household.

- Code blue policies using more rational temperature thresholds consistent with the medical literature on the prevention of hypothermia and frostbite, and which ensure access to daytime indoor shelter for vulnerable homeless individuals and families.

- Revised discharge planning policies and procedures to prevent and regulate the discharge of patients from nursing homes and hospitals, to ensure that the needs of individuals with serious mental and physical disabilities are properly addressed and accommodated and that community placements other than homeless shelters are secured for them consistent with Olmstead requirements.

- Sufficient shelter capacity to meet the need for families whose homelessness cannot be prevented and to appropriately accommodate people with disabilities. Such capacity should allow families and individuals to be placed as close to their communities of origin as possible to avoid disruptions to school, medical care, employment, and social supports.

- Required mental health training for all personnel assigned to mental health shelters and intake facilities.

RECORD HOMELESSNESS IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

MODERN MASS HOMELESSNESS IN ITS FOURTH DECADE

- At the beginning of 2017, 62,692 men, women, and children slept in NYC homeless shelters each night. This was down slightly from the all-time high of 62,840 in November 2016.

- The shelter census has increased 4 percent since the same time last year and 79 percent since the beginning of 2007.

- Fueling today’s record homelessness was the steep and sustained increase that took place between 2011 and 2014, as a result of the previous administration’s elimination of all housing assistance programs for homeless families.

- Modern mass homelessness is a result of both poor policy decisions and economic conditions that have caused a decades-long increase in the disparity between rents and incomes for the lowest-income households. These same economic forces have kept a large number of the very lowest-income New Yorkers in a perpetual state of housing instability, even amidst the economic recovery following the Great Recession. (See Appendix for further detail on the economic context of record homelessness.)

ANNUAL NUMBER OF PEOPLE SLEEPING IN NYC SHELTERS

- Mayor de Blasio’s restoration of homeless families’ access to NYCHA and Section 8 housing and the creation of new rent subsidies have slowed the rate of increase in the shelter census, but more families and individuals continue to enter shelters than exit shelters each year.

- In fiscal year 2016, a record 127,652 unique individuals (including 45,692 children) spent at least one night in the shelter system – an increase of 54 percent since 2002.

- The housing instability remaining in the wake of the Great Recession and the cumulative effect of too few stable housing placements and supportive housing opportunities for homeless New Yorkers have created both a daunting demand for shelter and an equally formidable need to adjust housing goals accordingly.

HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION

- Members of families constitute three-quarters of the people staying in NYC shelters.

- Children comprise 38 percent of all individuals sleeping in shelters each night.

- A near-record number of families slept in shelters each night as 2017 began: 15,802 households.

- Nevertheless, the number of homeless children staying in shelters declined by more than 1,800 from the all-time high of 25,849 in December 2014, as the City succeeded in helping larger families move out of shelters into homes of their own.

- The number of single adults continues to reach a new record nearly every month and recently surpassed 15,000, as the number of supportive housing placements fell to the lowest level since 2010 (see Chart 14)

LENGTH OF STAY IN SHELTERS

- For every segment of the homeless population, the average length of stay now exceeds one year.

- The length of stay for families with children jumped 36 percent between 2010 and 2011, following the elimination of all rent subsidies for homeless families.

- Now that Federal housing placements have been resumed and long-term rental assistance is available, lengths of stay for families with children have finally begun to decline – after rising by 83 percent in the span of seven years. Between December 2015 and 2016, lengths of stay decreased by 7 percent for families with children (from 436 to 404 days).

- The length of stay for single adults continues to increase each year and, at 384 days, is now nearly 60 percent longer than it was in 2009.

- Adult families have the longest average length of stay – over 18 months – likely due to higher rates of disability within this segment of the population.

HOMELESSNESS POLICY REPORT CARD

HOUSING AND PREVENTION

HOUSING PLACEMENTS

City: B- (Most Improved)

State: D

New York City has made laudable progress in helping homeless families move out of shelters into homes of their own. New housing initiatives offering families access to permanent affordable homes have unquestionably helped to stem the precipitous increase in shelter demand that began in 2011. By reversing a near decade-long policy of denying homeless families priority access to public housing and Section 8 – and instead placing an average of 1,500 families in public housing and 1,500 families with Section 8 in each fiscal year 2015 and 2016 – the de Blasio administration took the first important steps needed to stabilize the shelter census. The provision of these critical housing resources represents a robust increase from the paltry 170 total NYCHA and Section 8 placements made by Mayor Bloomberg in 2013. Still, the number of these placements has yet to reach the levels of 2003-2005, when the City experienced the only multi-year decrease in the family shelter census in nearly two decades.

Between 2006 and 2014, the City dramatically reduced the use of Federal housing resources to help homeless families move out of shelters – a disastrous decision given that the rate at which formerly homeless households remain stably housed is the highest in these types of housing. From 1999 to 2005, New York City supplied an average of 3,989 Federal housing placements for homeless families each year. From 2006 to 2014, only a few hundred units per year were provided, and on average, 3,548 fewer homeless families per year received stable housing placements over these nine years. The accumulated deficit is 31,935 fewer Federal housing placements made during the nine-year period of the Bloomberg policy that withheld these vital housing resources from homeless families – a veritable “Lost Decade,” the effects of which are still being felt today.

By contrast, the de Blasio administration’s new City-initiated rent subsidies are a welcome effort to help thousands of families and single adults finally move into their own apartments. In 2015, more than 2,700 families and single adults moved out of shelters with LINC and CityFEPS. In 2016, nearly 6,000 placements were made with a combination of LINC, CityFEPS, SEPS, and HOME TBRA. [2] Initial data from the first four months of fiscal year 2017 suggest placement levels will rise to nearly 7,000 by the end of the fiscal year.

The number of stable housing placements for families has reached the highest level since 2004 as a result of increased placements with NYCHA, Section 8, and City rent subsidies. The number of single adults placed in stable housing is at its highest level since 2002, due to the increase in subsidized placements through City rent subsidies. However, the percentage of single adults provided with stable housing placements is still just 20 percent, despite increasing every year for the past six years. More critically, for both families and single adults, the increase in placements to stable housing has not kept pace with increases in the demand for shelter: There were only 9,139 stable housing placements made among the 32,000 households that exited shelters in 2016 – meaning that more than two-thirds of the households in shelters did not receive stable housing placements.

There is no doubt that the City’s continued under-utilization of Section 8 vouchers and NYCHA apartments to house homeless families – especially in light of the lingering effects of the “Lost Decade” – is causing too many families to remain in shelters for too long, and is a self-defeating obstacle that stands in the way of a reduction in the shelter census.

These improvements in housing placements, stability, and permanency for homeless single adults and families have occurred despite inadequate investment by the State. The State has capped and cut its contributions toward the cost of both housing subsidies and homeless shelters (see below). In 2016, New York State provided a mere 14 percent reimbursement for the cost of City rent subsidies, or just 17 percent of the non-Federal costs. The City spent nearly five times as much as the State to provide rent supplements for homeless families and single adults.

SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

City: A

State: INCOMPLETE

Recognizing the dire need for more supportive housing as the third New York/New York housing agreement expired last year, both Mayor de Blasio and Governor Cuomo made bold commitments to create a total of 35,000 units of supportive housing over the next 15 years (30,000 in New York City and 5,000 elsewhere in the state). The City plans to open the first new supportive housing units this year, including crucial scattered-site units that can be provided quickly while additional units are sited, financed, and built. Funding for all 7,500 of the City’s brick and mortar new construction units has recently been made available via an open request for proposals, enabling supportive housing developers and investors to hit the ground running as they seek to site and finance this critically needed new housing.

Unfortunately, progress on the Governor’s commitment has needlessly been stalled by self-imposed roadblocks. In his January 2016 State of the State address, Governor Cuomo committed to funding 20,000 supportive units statewide over 15 years. The first 6,000 units (about $1 billion) were to be funded in last year’s budget – but when the spending plan was finalized in April, the $2 billion appropriated for supportive and affordable housing was restricted from use pending the execution of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) by the Governor and Legislative leaders. As the legislative session came to a close in June 2016, the leaders signed a pair of small MOUs to fund a one-year allotment: Only 1,200 units. Even as homelessness rose again to new records, the Governor and Legislative leaders have failed to negotiate and complete the MOU required to release the remaining $1.9 billion provided for affordable and supportive housing in last year’s budget.

Meanwhile, the dearth of supportive housing units has left more New Yorkers languishing in shelters and on the streets for longer periods of time: Supportive housing placements as a proportion of single adult shelter residents has reached a 10-year low, and is 39 percent below the peak in 2009 when 9,000 fewer people resided in the single adult shelter system.

HOMELESSNESS PREVENTION

City: A

The de Blasio administration has made significant strides in decreasing evictions through increased funding for legal services to assist low-income tenants, and offering both emergency and ongoing rental assistance to prevent homelessness. The administration invested over $100 million in legal services for low-income tenants in 2017, building upon prior increases initiated in 2013. This proactive approach of helping families and individuals to stay in their homes has yielded a dramatic decrease in residential evictions despite the city’s worsening housing affordability crisis. Residential evictions dropped 23 percent between 2013 and 2016, marking the second straight year that total residential evictions were under 23,000 – lower than any time since at least 2006. The City justifiably celebrates the fact that 40,000 people were able to stay in their homes and, as a result, eviction is no longer the leading cause of homelessness among families. Additionally, Mayor de Blasio and Speaker Mark-Viverito recently announced a five-year plan to guarantee universal access to legal counsel for low-income tenants in housing court as a strategy to further prevent evictions among those at risk of homelessness.

The City’s suite of housing subsidy programs and the provision of emergency rental assistance have also enabled more New Yorkers to remain stably housed in their own apartments, and protected them from the all-too-common experience of homelessness. The City has provided emergency rental assistance to 161,000 households at risk of losing their homes due to excessive rent burdens, enabling them to avoid homelessness. Further, among all City-funded housing subsidies from 2015 to 2017 (LINC, CityFEPS, SEPS, and HOME TBRA), nearly one in five was provided as a means of homelessness prevention. Using housing subsidies to prevent homelessness saves taxpayers the exorbitant cost of shelter ($44,000 per year for families and $34,500 for single adults) and enables families to avoid the trauma of losing their homes – and the months, if not years, of residential instability that typically follow an eviction. In many cases, it also helps keep rent-regulated housing affordable and less likely to become unregulated or subject to a vacancy bonus that would increase the rent beyond the normally authorized annual increases.

STREET HOMELESSNESS

SAFE HAVENS AND STREET OUTREACH

City: B-

Thousands of vulnerable individuals continue to live on the city’s streets, in transportation terminals, and in abandoned buildings. Last year, Mayor de Blasio created a new HOME-STAT program to increase outreach activities to offer more help to unsheltered New Yorkers. As part of this renewed focus on street homelessness, the de Blasio administration also increased the number of safe haven beds (in low-threshold shelters for chronically homeless individuals) by 15 percent between January 2016 and January 2017. The City reports having helped 690 individuals move into shelters or housing from the streets. However, the prospect of these homeless men and women finding permanent homes is, regrettably, limited by a severe and growing shortage of permanent supportive housing – long proven as a cost-effective solution to chronic homelessness. There is currently only one unit available for every six individuals approved for supportive housing.

CODE BLUE POLICIES FOR EMERGENCY WINTER WEATHER CONDITIONS

City: D

State: C-

An effective “code blue” policy is one that protects individuals and families from dangerous temperatures and weather conditions by easing access to shelters and drop-in centers, increasing street outreach, and opening warming centers. While the City and the State have each released code blue policies, both are flawed. The City’s code blue policy takes effect after 4 p.m. when the temperature falls to 32 degrees and ceases at 8 a.m., regardless of temperature or weather conditions. Low temperatures, wind, and damp weather endanger people exposed to the elements and can lead to cold weather injuries or even death due to hypothermia and frostbite. Hypothermia can occur at temperatures well above 32 degrees, and those particularly susceptible to it include infants, the elderly, and those suffering from malnutrition, alcoholism, and endocrine disorders.[3] The City’s code blue emergency procedures take effect only during evening hours even if dangerous weather conditions like heavy snow are present during the day. This arbitrary rule has caused men, women, and children taking refuge in a shelter during the night to be forced out into subfreezing temperatures or snow at 8 a.m.

An effective “code blue” policy is one that protects individuals and families from dangerous temperatures and weather conditions by easing access to shelters and drop-in centers, increasing street outreach, and opening warming centers. While the City and the State have each released code blue policies, both are flawed. The City’s code blue policy takes effect after 4 p.m. when the temperature falls to 32 degrees and ceases at 8 a.m., regardless of temperature or weather conditions. Low temperatures, wind, and damp weather endanger people exposed to the elements and can lead to cold weather injuries or even death due to hypothermia and frostbite. Hypothermia can occur at temperatures well above 32 degrees, and those particularly susceptible to it include infants, the elderly, and those suffering from malnutrition, alcoholism, and endocrine disorders.[3] The City’s code blue emergency procedures take effect only during evening hours even if dangerous weather conditions like heavy snow are present during the day. This arbitrary rule has caused men, women, and children taking refuge in a shelter during the night to be forced out into subfreezing temperatures or snow at 8 a.m.

The State’s “Emergency Measures for the Homeless During Inclement Winter Weather” policy similarly does not address the serious health threats that exist at temperatures above 32 degrees, nor does it ensure consistent access to shelters during the day. The State policy does include wind chill, but the 32-degree temperature threshold is too low. The NYS Department of Health each year warns operators of State-licensed nursing homes that hypothermia can occur when indoor air temperatures are 60 to 65 degrees. The State’s code blue policy does not clearly require localities to make shelters available all day in inclement weather, and permits New York City to turn away men, women, and children during the day. The only way to ensure that New Yorkers experiencing homelessness are not exposed to the dangers of hypothermia and frostbite is to require that shelters remain open at all times when weather conditions pose a threat to their wellbeing.

INTAKE AND ELIGIBILITY

City: D

State: D

When homeless families apply for shelter in New York City, they endure a grueling, multiple day investigation, at the end of which far too many are wrongly turned away and left to begin the whole stressful process again by reapplying. Recent policy changes have made the process even more demanding and error-prone. In November 2016, the State and City quietly agreed to modify a directive that governs which homeless families can qualify for a shelter placement, which rolled back earlier sensible improvements and has made it more difficult for homeless families to prove their eligibility.

As a direct result, too many homeless families are once again being found ineligible for shelter when City investigators erroneously send families back to stay in housing that is not actually available to them. Following implementation of the modified directive, the percentage of homeless families approved for shelter dropped far below the average for prior months – from a high of 50 percent in October 2016 to a low of 42 percent in December. This represents the lowest eligibility approval rate since 2011. This change is forcing more truly homeless families to reapply for shelter in order to receive a correct eligibility determination – often leaving them no choice but to take shelter in emergency rooms, subway stations, or 24-hour businesses, and to miss school or work as they repeat the arduous shelter application process multiple times. The hardship is real: The percentage of homeless families forced to apply for shelter two or more times before being found eligible increased from 37 percent in July to 45 percent in December 2016.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

MENTAL HEALTH AND MEDICAL NEEDS

City: D

State: C

A significant number of homeless single adults have serious medical and/or mental health needs. National estimates indicate that nearly one-third of homeless single adults in shelters likely suffer from a severe mental illness and/or chronic substance use disorder – and the rates are even higher for those not staying in shelters.[4] A recent noticeable increase in the number of people discharged from nursing homes to homeless shelters reflects changes in both policy and practice that are not yet fully understood. They are undoubtedly related to the State’s shift to Medicaid Managed Care for populations previously exempt, and new “pay for performance” reforms in health care systems that incentivize fewer and shorter stays in hospitals and nursing homes. Shelters are, for the most part, not equipped to meet the needs of individuals with significant medical or mental health conditions.

Often, people are discharged from facilities against their will: Half of the 120 nursing home discharge appeals lost each year by New York City residents are from nursing homes to homeless shelters, with the explicit approval of the State Health Department.[5] As the shelter system becomes a last resort for many low-income individuals discharged from hospitals, nursing homes, or psychiatric facilities, many find themselves without access to proper health and mental health care.

Homeless adults are assigned either to a general population shelter or a specialized shelter, depending on their circumstances. However, specialized shelters for those with mental health and medical needs are struggling to adequately address such needs and have difficulty securing more appropriate permanent housing placements. Specialized shelters are designed to provide some additional supports, but they were never intended to be a replacement for nursing homes and hospitals for those who lack the ability to live independently.

Below are anonymous examples of the types of serious disabilities that make living in a shelter extremely challenging for many homeless individuals:

During the two years DG has been homeless, he has watched his health deteriorate. He takes 22 medications daily to deal with his high cholesterol, diabetes, chronic pain, back problems, and high blood pressure. He struggles to navigate the crowded shelter using a walker or a cane. After his triple-bypass heart surgery in December, he was discharged from the hospital and returned to his shelter. Managing these various health conditions would be difficult in any setting, but DG finds it nearly impossible to maintain his precarious health in a shelter. Most recently, he was sent to the hospital with pneumonia for two days – one of many examples of his perpetual cycling between the hospital and the shelter. These frequent hospitalizations have caused him to miss critical public assistance appointments, which resulted in him losing his Medicaid and his Access-a-Ride transportation. He feels increasingly frustrated with every passing day in the shelter, and is trying his best to avoid yet another hospitalization.

When SN had his leg amputated due to diabetes complications, he had no idea that it was the beginning of his descent into homelessness. He stayed at a nursing home/rehab facility in Brooklyn for 13 months before being discharged, with the hope of being transferred to an assisted living facility. When that plan fell through, he was left with nowhere to turn but the shelter system. Even showering in the shelter is an ordeal: SN, who uses a walker and a prosthetic leg to get around, is constantly afraid of slipping. He also has problems with storing his medications at the shelter, and he has not been taking his prescribed insulin because he is concerned about his inability to properly refrigerate it. Despite his visible disability, his application for disability benefits was recently denied, depriving him of vital resources that could help him move into a home of his own.

JS has been homeless for over three years and uses a wheelchair. An accident left him with no motor function below the waist. Additionally, he suffers from high blood pressure, COPD, and asthma, and he has multiple fans near his shelter bed to enable him to breathe comfortably. He has had inconsistent case management at the shelter, which has at times derailed his attempts to move into permanent housing. He has had an extremely difficult time finding housing that is affordable and wheelchair accessible, even with the help of a City rent subsidy. He feels stuck, both figuratively and literally because of the insufficient transportation for himself and other shelter clients who use wheelchairs. There are so many clients with wheelchairs in his shelter that the van that takes people to appointments is always overbooked, which regularly causes JS and others to miss important appointments.

After AH suffered two strokes that left her unable to walk or use her hands, the hospital discharged her to a homeless shelter because she had no money or family able to take care of her. The hospital failed to follow protocol and alert the shelter, which was not equipped to provide the level of care AH needed – such as assisting her with bathing, eating, or taking her 13 prescription medications. She was soon re-hospitalized due to dehydration, but was subsequently again discharged to the shelter. Some of her medication was lost during a transfer to another shelter, and her extremities became so swollen that she could not fit a shoe on her foot. In addition to her physical struggles, AH says this harrowing situation has taken a terrible toll on her emotional wellbeing.

DISABILITY ACCOMMODATIONS

City: D

The higher rates of disability and health problems experienced by homeless individuals and families necessitate accommodations of various kinds, but the shelter system fails to provide adequate facilities and services for those with disabilities. In many cases, this has resulted in serious violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and in the worst instances has denied basic shelter to the most vulnerable homeless people. Recent litigation brought by the Legal Aid Society on behalf of the Coalition for the Homeless and Center for Independence of the Disabled-NY cited the following problems:

- The Department of Homeless Services lacks a systematic approach for screening and assessing the functional needs of clients with disabilities, resulting in uninformed assessments and inappropriate shelter placements — or no placement whatsoever. For example, those with hearing or visual impairments are often denied necessary American Sign Language interpreters or materials in alternate formats; individuals in need of personal care, home care, or in-home nursing care are unable to receive those services in most shelters; and those dependent on medical devices (such as mobility aids or enhanced oxygen support) are often unable to access shelters, store their devices, or use bathing and other shared shelter facilities due to architectural barriers.

- DHS lacks a consistent and effective approach to advise homeless clients with disabilities of their right to reasonable accommodations. Homeless individuals with disabilities do not receive adequate information about the process for obtaining accommodations, nor do they receive adequate information about the grievance process in the event that DHS fails to accommodate their needs.

- DHS does not provide sufficient staff training regarding the right to reasonable accommodations for disabilities and has no reliable system for record-keeping or case management to ensure that information relating to the disabilities of applicants and the accommodations they require are available to staff in accordance with the law.[6]

On far too many occasions, DHS has no vacant specialty beds for men or women with psychiatric disabilities, and often declines to provide any shelter placement at all for them until a bed in a mental health shelter becomes available. Further, there are too few shelter beds in Transitional Living Community (TLC) programs for homeless men (facilities which specifically help individuals with psychiatric disabilities develop independent living skills), and more are needed to help these vulnerable clients prepare to move into the supportive housing units that will become available under the Mayor’s and Governor’s new initiatives.

EFFORTS TO IMPROVE SHELTER CONDITIONS

City: B-

State: B-

New York City and New York State share regulatory responsibility for the oversight of facilities providing shelter to homeless New Yorkers. They are each also party to the consent decree in the Callahan v. Carey right to shelter litigation, to which the Coalition for the Homeless is also a party. The decree includes standards for the provision of shelter accommodations for single adults. The Coalition is the court-appointed monitor of those facilities and the City-appointed monitor of the facilities serving homeless families.

Heightened awareness of the abysmal physical conditions in many shelters has spurred a concerted effort by all parties to document and correct the problems. Since the City implemented a coordinated procedure to track and address conditions at shelters in late 2015, the number of recorded violations per shelter has decreased by an average of 83 percent at all non-cluster site facilities.[7]

Assisting in the effort to improve shelter conditions, the State has for the first time established State and local oversight mechanisms for all facilities offering shelter accommodations to homeless people, and added 73 full-time inspectors[8] to fulfill this responsibility.

One notable success in the stepped-up oversight of shelters is that safe havens and veterans facilities now have the lowest average number of violations per site, at just two per shelter.

However, pressing issues remain. Among non-cluster site facilities, those sheltering adult families without children have the greatest number of violations: An average of nine per site. Most troubling have been the persistently hazardous conditions found in cluster site apartments. On average, each cluster site address was cited for five additional violations between January 2016 and December 2016, even as the number of violations in other shelters was rapidly falling due to an intensive repair program undertaken by the City.

Despite the worsening conditions in cluster site units and the City’s original commitment to phase out the use of them by the end of 2019, the Department of Homeless Services continues to rely heavily on this inappropriate model of shelter for families: In December 2016, nearly 20 percent of all homeless families were living in cluster site units. Mayor de Blasio’s new plan to replace the use of cluster site apartments and commercial hotels (360 sites citywide) with 90 new shelters and the expansion of some existing shelters is admirable, but unfortunately delays the date by which the City will be out of cluster sites from 2019 to 2021.

HOMELESS CHILDREN AND STUDENTS

City: C-

The City has made far too little progress for the 45,000 children staying in shelters each year. The number of children in shelters remains at record levels and was effectively the same in 2015, although the City was successful in at least stemming the rapid rate of increase that brought over 8,000 more children into shelters in between 2012 and 2016 – an increase of over 22 percent.

In response to the persistent advocacy of the Legal Aid Society and Coalition for the Homeless, DHS finally modified the intake and shelter placement process for families in order to solve a pernicious problem that had forced many homeless children to miss school. As of late 2016, children are no longer required to be present at every PATH shelter intake appointment – they must be there only for the initial appointment. Nevertheless, many families continue to bring their children to PATH appointments due to other problems such as no access to school transportation, extremely long waits at PATH, and lack of childcare.

The average school attendance rate for children in DHS shelters has not improved significantly during Mayor de Blasio’s tenure. In 2017 to date, homeless children in DHS shelters attended school only 84 percent of the time, on average. School attendance is directly affected by how well the City succeeds in placing families in shelters near their children’s schools. The proportion of families provided with a shelter placement near the school attended by their youngest child has decreased by half since 2005. As the shelter system has strained under record homelessness, a very serious shortage has developed in the City’s capacity to provide shelter placements closer to families’ schools, day care centers, community ties, and health care providers. The Mayor’s new plan to site shelters in homeless families’ communities of origin is a welcome step in the right direction for reducing displacement, improving school attendance, and helping homeless families retain access to their communities, jobs, and support systems.

The City Council’s March 2017 proposed package of bills to revamp the City’s Fair Share rules would, on the other hand, ignore the needs of homeless families and children to remain near existing social supports. The proposed legislation would do little more than foster the rejection of homeless shelters and other vital transitional housing and human services without providing a vehicle to accomplish their needed placement, resulting in continued capacity strains that would make it difficult to place families near their children’s schools.

The number of homeless students in shelters (including those operated under the auspices of agencies other than the Department of Homeless Services) has reached its highest level since the 2011-12 school year. Moreover, the number of doubled-up school-aged children increased by 26 percent between the 2014-15 and the 2015-16 school years, a reflection of the growing number of families who are unstably housed – on the brink of losing their precarious hold on a place to live and needing a shelter placement.

MEETING THE UNPRECEDENTED NEED FOR SHELTER

State: F

Governor Cuomo’s budgeting practices have resulted in a massive withdrawal of State resources to address poverty and homelessness, and nowhere has the pain of these reductions been more keenly felt than in New York City. From 2011 to 2017, the number of homeless family households and single adults staying in NYC shelters rose 60 percent. During the same period, the total cost of sheltering homeless families in NYC increased by $435 million. The City has shouldered 36 percent of this increase ($156 million), while the State contributed a mere 3 percent ($13 million). The State shifted most of the costs it had previously borne to localities and the Federal TANF block grant.

For single adult shelters, the fiscal disparity is even worse. Between 2011 and 2017, the total cost of sheltering homeless single adults doubled, increasing by $263 million. The City has shouldered roughly 90 percent of this increase ($235 million), while the State contributed only 10 percent ($26 million).[9]

The State’s failure to contribute equally to the shared obligation to provide shelter and services for an unprecedented number of New Yorkers in need has left New York City to bear the bulk of the increased cost on its own, while the State has avoided providing $176 million it should otherwise have supplied.

PROJECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

HOUSING SOLUTIONS

With family and single adult homelessness remaining stubbornly at record levels, the City and State must implement solutions on a scale to meet the magnitude of the need.

To help homeless families, New York City must immediately:

- Increase the number of public housing placements for homeless families from 1,500 per year to at least 3,000, and the number of Section 8 and HPD resources to at least 2,500 placements. At least 5,500 placements per year are needed to regain the ground lost as a result of the 32,000 placements denied to homeless families during the “Lost Decade.”

- Continue to place at least 3,000 families through City-funded rent subsidy programs each year.

These actions will result in more families leaving the shelter system than entering it, and will allow homeless families to regain and retain homes of their own for the long term. The number of families staying in shelters each night would thus be reduced by roughly 30 percent by 2020.[10]

For single adults, the solutions are also clear. Because they have historically been afforded few options for stable, affordable housing, more housing and subsidies must be provided to help them move out of shelters and into apartments.

To help single adults, New York City must immediately:

- Open new units of supportive housing under the Mayor’s 15-year, 15,000-unit commitment as quickly as possible. The faster these units are funded and occupied, the better, as they provide stable housing, save tax dollars, and benefit the neighborhoods in which they are located.

- Significantly increase the number of housing subsidies provided to homeless single adults from the current level of 2,000 placements per year to 3,000 subsidized placements per year.

- Provide at least 5,000 single adults with rent subsidies or supported housing per year – an imperative increase from the current 3,500 total annual placements through both programs.

The number of single adults staying in shelters would thus be reduced by nearly 10 percent by 2020 (see Chart 30 below).

For both families and single adults, the City must immediately:

- Create a new capital development program to finance construction of at least 10,000 units of affordable housing for homeless families and single adults over the next five years. The Mayor’s current affordable housing plan unfortunately fails to target nearly enough new housing for homeless families and individuals.

- Provide all homeless individuals and families with housing application and housing search assistance, including all individuals and families placed in hotels and cluster site apartments.

- Aggressively enforce the source-of-income anti-discrimination law with landlords who illegally reject families and individuals seeking to use housing vouchers to help pay their rent.

Taken together, these recommendations could help reduce the number of families and single adults staying in shelters and prevent their number from growing by thousands in the coming years. The total number of homeless people needing shelter each night could be reduced by up to 25 percent, and the census could be brought below 50,000 people per night by 2020.

New York State must also step up and play a much greater, more constructive role in addressing record homelessness in New York City following years of broken promises and delayed funding for supportive housing, the withdrawal of financial support for homeless shelters when the need is greatest, and shifting the costs to New York City and the counties.

The State must immediately:

- Release the $1.9 billion for affordable and supportive housing funds appropriated in 2016 and currently stalled due to inaction by the Governor and Legislative leaders.

- Implement Assembly Member Hevesi’s proposal to create a State-funded long-term rent subsidy program, known as Home Stability Support.

- Expand DRIE: The Disability Rent Increase Exemption program should be expanded to include households with a family member with a disability who is a child or an adult who is not the head of household. This would help such families retain their rent-stabilized housing and prevent their displacement to a system ill-equipped to meet their needs, and at the same time help prevent deregulation of their apartments.

SHELTER PROCESSES AND CONDITIONS

The City and State must also improve shelter conditions and processes in order to reduce the trauma of homelessness for families, children, and individuals, provide lawful accommodations for people with disabilities, reduce the length of shelter stays, and reduce overall disruption for homeless children and students.

New York City must:

- Open additional Transitional Living Community (aka “TLC”) shelter capacity – designed to provide intensive services to help people with psychiatric disabilities develop independent living skills – for homeless men with such needs.

New York State must immediately:

- Reverse harmful cuts to New York City’s emergency shelter system, and share equally with New York City in the non-Federal cost of sheltering homeless families and individuals.

The City and State together should implement:

- A less onerous shelter intake process in which 1) applicants are assisted in obtaining necessary documents, 2) the housing history documentation requirement is limited to a list of residences for six months, and 3) recommended housing alternatives are verified as actually available and pose no risks to the health and safety of applicants or to the continued tenancy of a potential host household.

- Code blue policies using more rational temperature thresholds consistent with the medical literature on the prevention of hypothermia and frostbite, and which ensure access to daytime indoor shelter for vulnerable homeless individuals and families.

- Revised discharge planning policies and procedures to prevent and regulate the discharge of patients from nursing homes and hospitals, to ensure that the needs of individuals with serious mental and physical disabilities are properly addressed and accommodated and that community placements other than homeless shelters are secured for them consistent with Olmstead requirements.

- Sufficient shelter capacity to meet the need for families whose homelessness cannot be prevented and to appropriately accommodate people with disabilities. Such capacity should allow families and individuals to be placed as close to their communities of origin as possible, to avoid disruptions to school, medical care, and other social supports.

- Required mental health training for all personnel assigned to mental health shelters and intake facilities.

APPENDIX: ECONOMIC CONTEXT OF RECORD HOMELESSNESS

RENTAL HOUSING VACANCY RATES

- The vacancy rate of 3.45 percent for all rental housing in NYC remains at emergency levels and has justified two years of rent freezes by the Rent Guidelines Board.

- Further, vacancy rates for the lowest-cost units are far below the average for all rentals, and underscore the profound need for affordable housing targeted to households with the lowest incomes.

- The vacancy rate for the lowest-cost units that rent for under $300 per month has been at or below 1 percent for the last 17 years, and this is the only housing affordable to small households living on public assistance and Supplemental Security Income or Unemployment Insurance.

RENT BURDENS

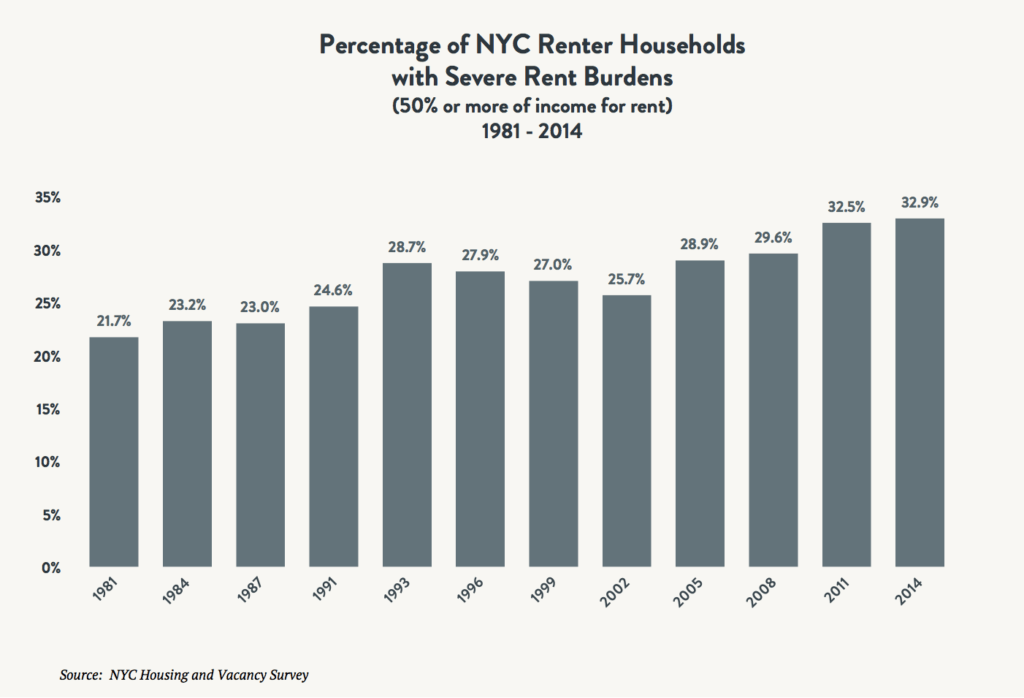

- Rent burdens for all households have continued to rise since 1981.

- As of 2014, one-third of all renters were paying more than half of their incomes on rent.

- High rent burdens among the lowest-income New Yorkers are nearly universal. On average, 80 percent of those with incomes under $35,000 per year pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent, and nearly 60 percent pay more than half of their income on rent.

- The proportion of households paying more than half of their income on rent grew by more than 50 percent between 1981 and 2014.

CROWDING

- The number of renter households with conditions of severe crowding has increased 30 percent since 1999.

- In 2014, 4.7 percent of all renter households were severely crowded.

- While the number of severely crowded households was fairly constant between 1999 and 2005, the number rose by over 24,000 households in the subsequent decade at a time of rapid population growth.

LOSS OF LOW-INCOME HOUSING

- Between 1996 and 2014, NYC lost more than 1.1 million apartments with contract rents below $800 per month, principally due to rent increases.

- During that time, the entire rental stock grew by 195,000 apartments.

- The percentage of all rental units with rents below $800 plummeted from 77 percent in 1996 to 17 percent in 2014.

- By 2014, NYC had fewer than 87,000 apartments affordable to small households relying on public assistance, Supplemental Security Income, or Unemployment benefits – nearly 150,000 fewer very low-cost apartments than in 1996.

- During the advent of modern mass homelessness in the early 1970s, New York City lost about 400,000 low-cost rental units to the policy known as vacancy decontrol. The policy was scrapped in the wake of skyrocketing rents, but those units forever lost their rent-regulated status. In 1993 and 1996, the NYS Legislature again adopted vacancy decontrol and vacancy bonus policies that resulted in the loss of 300,000 low-cost apartments.[11]

- By comparison, various mayors have implemented multi-year affordable housing production plans to build and preserve tens of thousands of units of housing, but they have not produced enough affordable housing to offset these losses.

- Mayor de Blasio’s plan to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing, “Housing New York,” contains the most ambitious goal of all the mayoral housing plans dating back to Koch, but fails to target nearly enough new housing for homeless families and individuals.

INCOME INEQUALITY

- A fundamental of the economics of homelessness is that in cities with low vacancy rates, high housing costs, and extreme income inequality, the people at the lowest end of the income spectrum fall out of the housing market altogether.

- According to the Fiscal Policy Institute’s 2017 budget analysis, the percentage of all income going to New York City’s top 1 percent has grown from 12.2 percent in 1980, when modern mass homelessness emerged as a public concern, to 40.9 percent in 2015, as the ongoing crisis again became a cause for widespread alarm.

- The Coalition for the Homeless first warned in 2000 that extreme income inequality had fundamentally altered the housing market in New York City with two grave consequences: “First, housing costs at the bottom end of the market were driven up by rising demand for fewer units among a growing number of poor households; and second, the poorest households were pushed out of the housing market entirely, and became homeless.”[12]

- We warned then that new housing production in the 1990s was half what it had been in the 1970s, and that the housing shortage was exacerbated by robust population growth.

POPULATION GROWTH

- In 1996 the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council projected that New York City’s population would reach 7.94 million people in 2020, but it actually reached 8 million in 2000, twenty years earlier than anticipated.[13]

- A subsequent census forecast projected a population of 8.5 million in New York City by 2020, but it reached that level early as well, in 2015.[14]

- The NYC population grew at a rate of nearly 71,500 people per year between 2010 and 2015, to 8.55 million people, and could top 8.9 million by 2020 (if not earlier). That would be roughly 350,000 more people than projected.

- The census is expected to grow by 75,000 per year in the next several years. [15]

- Based on that expectation, our projection shows that the 2025 NYC census would exceed the projected census by more than 500,000 people – resulting in a city population of nearly 9.3 million, rather than the 8.7 million originally forecast.

- As we warned a decade and a half ago, we now face even more calamitous housing problems than we did then, and for unambiguous reasons. With the population growing at this rate, it is clear that more housing must be built to accommodate far more households than anticipated. The investments needed to address this must take place now.

UNEMPLOYMENT

- While New York City’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate has generally declined since the end of the Great Recession, the city’s shelter census has continued to climb.

- A high number of housing placements blunted the impact of two previous periods of high unemployment, which enabled the shelter census to stabilize despite the economic downturn.

- In the wake of the Great Recession, renters with the lowest incomes have been pushed out of the housing market entirely. Current housing resources have proved insufficient to help enough New Yorkers regain their footing in homes of their own.

References

[1] See [10] for full methodology

[2]LINC: Living in Communities Rental Assistance Program; SEPS: Special Exit and Prevention Supplement; CityFEPS: City Family Eviction Prevention Supplement; HOME TBRA: Home Tenant-Based Rental Assistance; For more information about individual City subsidy programs, see: http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/get-help/im-in-need-of-housing/

[3] O’Connell, J., Petrella, D., Regan, R. (2004). Accidental Hypothermia and Frostbite: Cold-Related Conditions. The Health Care of Homeless Persons: A Manual of Communicable Diseases & Common Problems in Shelters & on the Streets, published by Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. See also: Biem, J., Koehncke, N., Classen, D., Dosman, J. (2003) Out of the cold: management of hypothermia and frostbite. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC140473/

[4] Current Statistics on the Prevalence and Characteristics of People Experiencing Homelessness in the United States (2011). SAMHSA

[5] NYS Department of Health verbal report, 2014

[6] Butler v. City of New York, 15-CV-3783 (S.D.N.Y.)

[7] Cluster site facilities are apartments (many of which are subject to rent regulation) that are rented by the City for the purpose of providing shelter to families. They are characterized by notoriously poor conditions, high costs, and a dearth of services.

[8] NYS Executive Budget Agency Presentation Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance Budget Highlights.

[9] Source: Independent Budget Office

[10] Methodology for the following projection graphs is as follows: The Mayor’s plan, Turning the Tide on Homelessness in NYC, projects that the total shelter census will decrease by 2,500 people over the next five years. This reduction is a combination of a reduction in the family shelter census that counteracts a predicted increase in homeless single adults. The Mayor’s plan assumes that “the single adult census will increase at about the annual rate it has increased over the past decade.” At the current rate, the single adult shelter census will rise by approximately 3,000 people in five years. Therefore, the family census must decrease by 5,500 people in five years to account for the total projected shelter census decline of 2,500 over five years. This report assumes an average family size of three, consistent with City assumptions. This report also assumes the reduction will be spread out evenly over five years. Coalition for the Homeless projections are based on assumptions about the number of families and single adults entering and leaving shelters. Stable exits from shelters will increase by the amounts recommended in our report and entries will decrease slightly as a result of reduced instability and shelter returns. The number of shelter residents exiting without subsidies is projected to be similar to years when a greater number of stable housing options were available.

[11] http://metcouncilonhousing.org/get_involved/reform_our_rent_regulation_laws

[12] Markee, P., Coalition for the Homeless (2002). Housing a Growing City: New York’s Bust in Boom Times, Second Edition (First Edition 2000). See also: O’Flaherty, Brendan (1996). Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness (Harvard University Press).

[13] Markee, P., Coalition for the Homeless (2002). Housing a Growing City: New York’s Bust in Boom Times, Second Edition.

[14] New York 1 (2016): http://www.ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/news/2016/03/23/nyc-s-population-tops-8-5-million-for-first-time–new-censusfigures-show.html

[15] Mayor’s Office of Operations, City of New York (2016). Social Indicators Report.

http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/Social-Indicators-Report-April-2016.pdf