For generations, homeownership has been foundational to the American Dream and establishing generational wealth. A home is a symbol of stability, comfort, and the promise of a better future. But as we all know, homeownership is not the reality for many, and certainly was not the case for Black families living in New York City’s redlined neighborhoods in the 20th century.

Image credit: Granddaughter Celeste G. Lumpkins-Moses & Family.3

So, this Black History Month, we are sharing the story of civil rights and community activist Elsie Richardson, a fierce and powerful voice for Black communities and fighter against the systems erected to hinder their quest for the American Dream.

So, this Black History Month, we are sharing the story of civil rights and community activist Elsie Richardson, a fierce and powerful voice for Black communities and fighter against the systems erected to hinder their quest for the American Dream.

Elsie Richardson was born in 1922 to Caribbean immigrants from Nevis and became one of Brooklyn’s most influential community organizers. Elsie’s journey as an activist began in her teenage years in Harlem, participating in civil rights campaigns including the 1941 bus boycott led by Adam Clayton Powell Jr. to force the City to hire Black bus drivers. She was also the only Black student at Washington Irving High School and often the only Black individual in many of the offices in which she subsequently worked. However, it was in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where she would leave her most indelible mark on civil rights history and urban development. When Elsie moved to Bed-Stuy after World War II, the neighborhood was a vibrant, mixed-income community.1

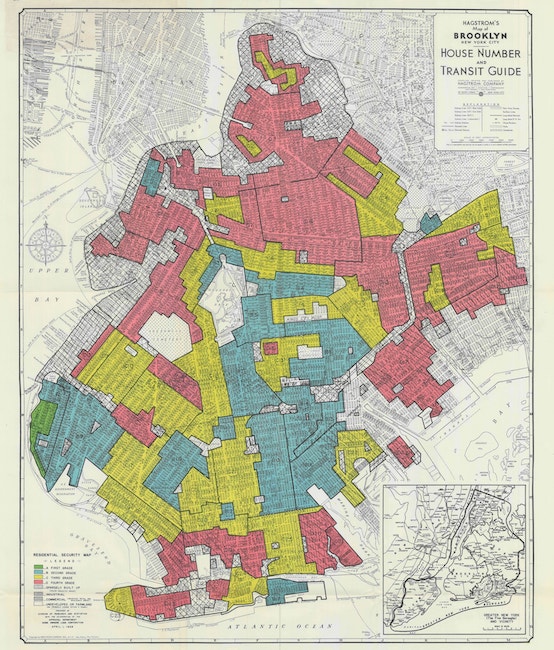

Enter redlining.

Redlining is the practice of denying people access to credit because of where they live, even if they are personally qualified for loans. Historically, mortgage lenders would take literal red markers, and draw a red line around ‘undesirable neighborhoods’, which were largely Black-populated neighborhoods.2

Image credit: National Archives and Records Administration, Mapping Inequality3

Without access to bank loans or credit, fewer homes and businesses in Bed-Stuy could be renovated. Residents were left to fend for themselves; and the impacts were severe. The once thriving, and lively neighborhood became a center for housing discrimination, political segregation, and denial of basic City services. By the mid-1960s, Bed-Stuy had become one of New York City’s poorest neighborhoods.3

Understanding that the neighborhood’s challenges were both political and economic in nature, Elsie, together with other community leaders, including future Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, helped establish the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council (CBCC).4 This umbrella organization became a powerful force in advocating for the community’s needs and fighting against discrimination.

Elsie’s signature moment occurred on a frigid February day in 1966, when she led Senator Robert F. Kennedy on a lengthy tour of the impoverished, majority-black Brooklyn neighborhood of Bed-Stuy. When Kennedy suggested yet another study of the neighborhood’s problems, Richardson delivered her famous retort: “We’ve been studied to death, what we need is bricks and mortar!” This powerful statement encapsulated the community’s frustration. It was always analysis, but no real action.5

Elsie’s bold challenge spurred Kennedy to act. Building on the comprehensive neighborhood renewal plan Elsie had already developed through the CBCC, Kennedy worked with her to establish what would become the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (BSRC) in 1967.6 This groundbreaking initiative has become a model for community development corporations across the nation.

The impact of Richardson’s vision through the BSRC has been transformative. The organization has facilitated over $500 million in investments and $60 million in mortgage financing, created job placement programs, and built affordable housing. In fact, housing and homeownership is a pillar of BSRC’s services. They contend that housing is “one of the most beneficial means to asset-building, wealth accumulation and generational wealth. In the course of our history, we have developed and/or preserved over 7,800 affordable housing units.”6

Elsie Richardson’s work demonstrates the power of grassroots organizing and the importance of demanding concrete action. While analysis is important, communities ultimately need tangible and comprehensive investment in their neighborhoods and in affordable housing for the lowest income New Yorkers.

Through her tireless work, Elsie not only helped transform Bed-Stuy, but also created a blueprint for community development in New York and all urban renewal efforts across the United States. Elsie serves as an inspiration to our City and State leaders today, because the fulfillment of the American Dream should not be for the few, rather the many.

References

1 Elsie Richardson, https://www.ilovebedstuy.com/work/elsie

2 Redlining, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining

3 Elsie Richardson: Investing in Bed-Stuy, https://www.mcny.org/story/elsie-richardson-investing-bed-stuy

4 Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council, https://communitydevelopmentarchive.org/central-brooklyn-coordinating-council/

5 Remembering Elsie Richardson, Michael Woodsworth, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/remembering-elsie-richardson/ (April 10, 2012)

6 Restoration Plaza History, https://www.restorationplaza.org/about/history/